The past two decades have brought a massive increase in knowledge about the human gut microbiota and its links to human health through diet. And although many people perceive that regular consumption of safe, live microbes will benefit their health, the scientific evidence to date has not been sufficiently developed to justify adding a daily recommended intake of live microbes to food guides for different populations.

Recently, a group of seven scientists, including six ISAPP board members, published their perspective about the value of establishing the link between live dietary microbes and health. They conclude that although the scientific community has a long way to go to build the evidence base, efforts to do this are worthwhile.

The collaboration on this review was rooted in an ISAPP expert discussion group held at the 2019 annual meeting in Antwerp, Belgium. During the discussion, various experts presented evidence from their fields—addressing the potential health benefits of live microbes in general, rather than the narrow group of microbial strains that qualify as probiotics.

Below, the authors of this new review answer questions about their efforts to quantify the relationship between greater consumption of live microbes and human health.

Why is it interesting to look at the potential importance of live microbes in nutrition?

Prof. Joanne Slavin, PhD, RD, University of Minnesota

Current recommendations for fiber intake are based on protection against cardiovascular disease—so can we do something similar for live microbes? We know that intake of live microbes is thought to be health promoting, but actual recommended intakes for live microbes are missing. Bringing together a talented group of microbiologists, epidemiologists, nutritionists, and food policy experts moves this agenda forward.

Humans need proper nutrition to survive, and a lack of certain nutrients creates a ‘deficiency state’. Is this the case for live microbes?

Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD, ISAPP Executive Science Officer

I don’t think we’ll find that live microbes are essential in the same way that vitamins and minerals lead to deficiency diseases. After all, gnotobiotic animal colonies are viable. But I believe there is enough evidence to suggest that consumption of live microbes will promote health. Exactly how and to what extent remains to be established.

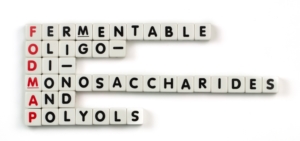

Why think about intake of ‘live microbes’ in general, rather than intake of probiotic & fermented foods specifically?

Prof. Maria Marco, PhD, University of California Davis

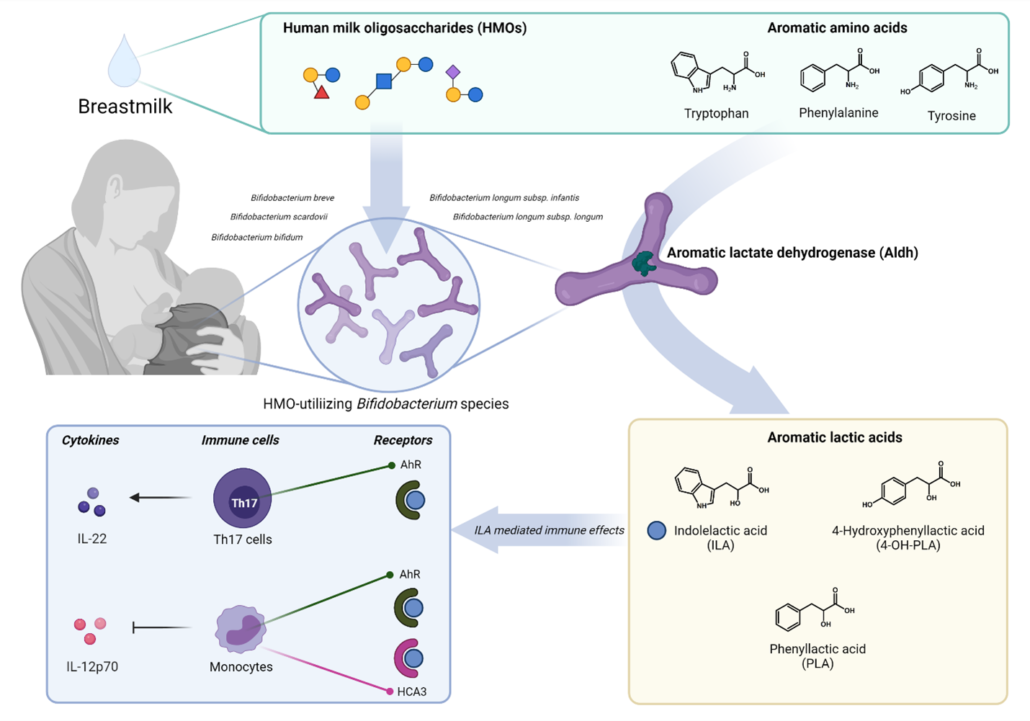

We are constantly exposed to microorganisms in our foods and beverages, in the air, and on the things we touch. While much of our attention has been on the microbes that can cause harm, most of our microbial exposures may not affect us at all or, quite the opposite, be beneficial for maintaining and improving health. Research on probiotic intake as a whole supports this possibility. However, probiotic-containing foods and dietary supplements are only a part of our dietary connection with live microbes. Non-pasteurized fermented foods (such as kimchi and yogurts) can contain large numbers of non-harmful bacteria (>10^7 cells/g). Fruits and vegetables are also sources of living microbes when eaten raw. Although those raw foods they may contain lower numbers of microbes, they may be more frequently eaten and consumed in larger quantities. Therefore, our proposal is that we take a holistic view of our diets when weighing the potential significance of live microbe intake on health and well-being.

What are dietary sources of live microbes? And do we get microbes in foods besides fermented & probiotic foods?

Prof. Bob Hutkins, PhD, University of Nebraska Lincoln

For tens of thousands of years, humans consumed large amounts of microbes nearly every time they ate food or drank liquids. Milk, for example, would have been unheated and held at ambient temperature with minimal sanitation and exposed to all sorts of microbial environments. Thus, a cup of this milk could easily have contained millions of bacteria. Other foods like fruits and vegetables that were also exposed to natural conditions could have also contained similar levels of microbes. Even water would have contributed high numbers of live microbes.

Thanks to advances in food processing, hygiene, and sanitation, the contemporary western diet generally contains low levels of microbes. Consider how many foods we eat that are canned, pasteurized, or cooked – those foods will contain few, in any live microbes. Fresh produce can serve as a source of live microbes, but washing, and certainly cooking, will reduce those levels.

For sure, the most reliable sources of dietary microbes are fermented foods and beverages. Even if a fresh lettuce salad were to contribute a million bacteria, a single teaspoon of yogurt could contain 100 times more live bacteria. Other popular fermented foods like kefir, kimchi, kombucha, and miso, can contain a large and relatively diverse assortment of live microbes. Other fermented foods, such as cheese and sausage, are also potential sources, but the levels will depend on manufacturing and aging conditions. Many fermented, as well as non-fermented foods are also supplemented with probiotics, often at very high levels.

What’s the evidence that a greater intake of live microbes may lead to health benefits?

Prof. Dan Merenstein, MD, Georgetown University

Studies have shown that fermented foods are linked to a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, reduced risk of weight gain, reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, healthier metabolic profiles (blood lipids, blood glucose, blood pressure and insulin resistance), and altered immune responses. This link is generally from associative studies on certain fermented foods. Many randomized controlled trials on specific live microbes (probiotics and probiotic fermented foods) showing health benefits have been conducted, but randomized controlled trials on traditional fermented foods (such as kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha) are rare. Further, no studies have aimed to assess the specific contribution of safe, live microbes in diets as a whole on health outcomes.

Why is it difficult to interpret past data on people’s intake of live microbes and their health?

Prof. Colin Hill, PhD, University College Cork

It would be wonderful if there were a simple equation linking the past intake of microbes in the diet and the health status of an individual (# MICROBES x FOOD TYPE = HEALTH). In reality, this is a very complex challenge. Microbes are the most diverse biological entities on earth, our consumption of microbes has not been deliberately recorded and can only be estimated, and even the concept of health has defied precise definitions for centuries. To further confuse the situation microbes meet the host in the gastrointestinal tract, the site of our enormously complex mucosal immune system and equally complex microbiome. But the complexity of the problem should not prevent us from looking for prima facie evidence as to whether or not such a relationship is likely to exist.

Databases of dietary information have data on people’s intake of live microbes, but what are the limitations of our available datasets?

Prof. Dan Tancredi, PhD, University of California Davis

Surveys often rely on food frequency questionnaires or diaries to determine consumption of specific foods. These are notoriously prone to recall error and/or other types of measurement error. So, even just measuring consumption of foods is difficult. For researchers seeking to quantify survey respondents’ consumption of live microbes, these challenges become further aggravated because the respondents would not typically know the microbial content in the foods they consumed. Instead, we would have to have them tell us the types and amounts of the foods they ate, and then we would need to translate that into approximate microbial counts—but even within a particular food, the microbial content can vary, depending on how it was processed, stored, and/or prepared prior to consumption.

See ISAPP’s press release on this paper here.