Bifidobacteria in the infant gut use human milk oligosaccharides: how does this lead to health benefits?

By Martin Frederik Laursen, Technical University of Denmark, 2022 co-recipient of Glenn Gibson Early Career Research Prize

Breast milk is the ‘gold standard’ of infant nutrition, and recently scientists have zeroed in on human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) as key components of human milk, which through specific interaction with bifidobacteria, may improve infant health. Clarifying mechanisms by which HMOs act in concert with bifidobacteria in the infant gut may lead to better nutritional products for infants.

Back in early 2016, I was in the middle of my PhD studies working on determinants of the infant gut microbiota composition in the Licht lab at the National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark. I had been working with fecal samples from a Danish infant cohort study, called SKOT (Danish abbreviation for “Diet and well-being of young children”), investigating how the diet introduced in the complementary feeding period (as recorded by the researchers) influences the gut microbiota development 1,2. Around the same time, Henrik Munch Roager, PostDoc in the lab, was developing a liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based method for quantifying the aromatic amino acids (AAA) and their bacterially produced metabolites in fecal samples (the 3 AAAs and 16 derivatives thereof). These bacterially produced AAA metabolites were starting to receive attention because of their role in microbiota-host cross-talk and interaction with various receptors such as the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) expressed in immune cells and important for controlling immune responses at mucosal surfaces 3,4. However, virtually nothing was known about bacterial metabolism of the AAAs in the gut in an early life context. Further, the fecal samples collected from the SKOT cohort were obtained in a period of life when infants are experiencing rapid dietary changes (e.g. cessation of breastfeeding and introduction of various new foods). Thus, we wondered whether the AAA metabolites would be affected by diet and whether these metabolites might contribute to the development of the infant’s immune system. Our initial results quickly guided us on the track of breastfeeding and bifidobacteria! Here is a summary of the story, published last year in Nature Microbiology5. (See the accompanying News & Views article here.)

We initially looked at the data from a subset of 59 infants, aged 9 months, from the SKOT cohort. Here we found that both the gut microbiome and the AAA metabolome were affected by breastfeeding status (breastfed versus weaned). It is well established that certain bifidobacteria dominate the bacterial gut community in breastfed infants due to their efficient utilization of HMOs – which are abundant components of human breastmilk 6. Our data showed the same, namely enrichment of Bifidobacterium in the breastfed infants, but also indicated that the abundance of specific AAA metabolites were dependent on breastfeeding.

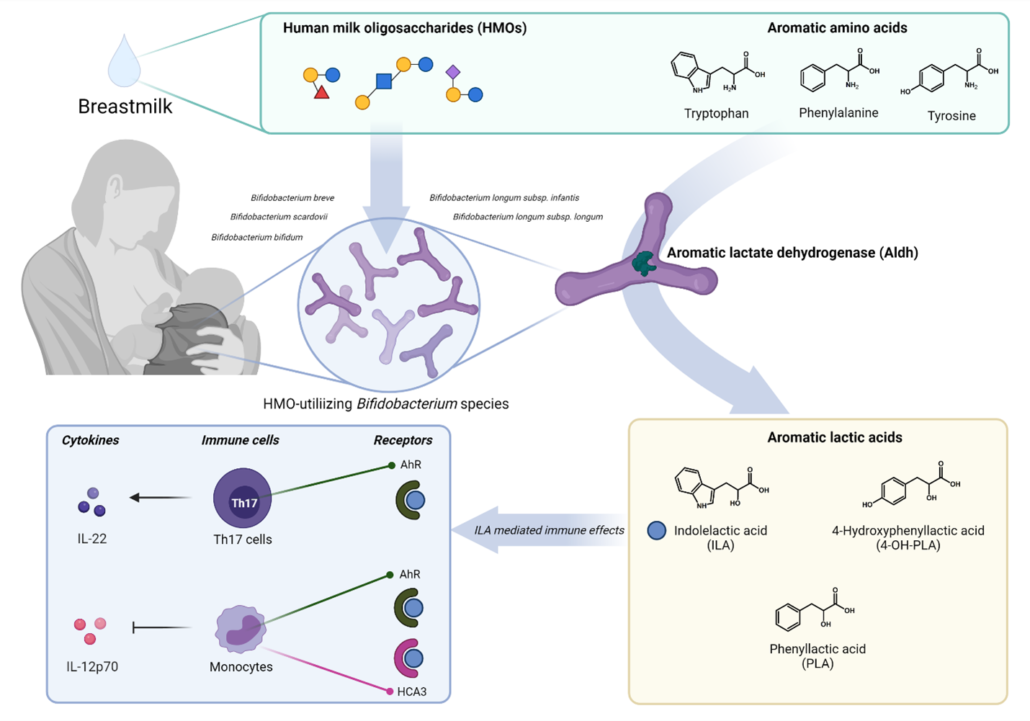

Trying to connect the gut microbiome and AAA metabolome, we found striking correlations between the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium and specifically abundances of three aromatic amino acid catabolites – namely indolelactic acid (ILA), phenyllactic acid (PLA) and 4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid (4-OH-PLA), collectively aromatic lactic acids. These metabolites are formed in two enzymatic reactions (a transamination followed by a hydrogenation) of the aromatic amino acids tryptophan, phenylalanine and tyrosine. However, the genes involved in this pathway were not known for bifidobacteria. Digging deeper we discovered that not all Bifidobacterium species found in the infant’s gut correlated with these metabolites. This was only true for the Bifidobacterium species enriched in the breastfed infants (e.g. B. longum, B. bifidum and B. breve), but not post-weaning/adult type bifidobacteria such as B. adolescentis and B. catenulatum group.

We decided to go back to the lab and investigate these associations by culturing representative strains of the Bifidobacterium species found in the gut of these infants. Indeed, our results confirmed that Bifidobacterium species are able to produce aromatic lactic acids, and importantly that the ability to produce them was much stronger for the HMO-utilizing (e.g. B. longum, B. bifidum and B. breve) compared to the non-HMO utilizing bifidobacteria (e.g. B. adolescentis, B. animalis and B. catenulatum). Next, in a series of experiments we identified the genetic pathway in Bifidobacterium species responsible for production of the aromatic lactic acids and performed enzyme kinetic studies of the key enzyme, an aromatic lactate dehydrogenase (Aldh), catalyzing the last step of the conversion of aromatic amino acids into aromatic lactic acids. Thus, we were able to demonstrate the genetic and enzymatic basis for production of these metabolites in Bifidobacterium species.

To explore the temporal dynamics of Bifidobacteria and aromatic lactic acids and validate our findings in an early infancy context (a critical phase of immune system development), we recruited 25 infants (Copenhagen Infant Gut [CIG] cohort) from which we obtained feces from birth until six months of age. These data were instrumental for demonstrating the tight connection between specific Bifidobacterium species, HMO-utilization and production of aromatic lactic acids in the early infancy gut and further indicated that formula supplementation, pre-term delivery and antibiotics negatively influence the concentrations of these metabolites in early life.

Having established that HMO-utilizing Bifidobacterium species are key producers of aromatic lactic acids in the infant gut, we focused on the potential health implications of this. We were able to show that the capacity of early infancy feces to in vitro activate the AhR, depended on the abundance of aromatic lactic acid producing Bifidobacterium species and the concentrations of ILA (a known AhR agonist) in the fecal samples obtained from the CIG cohort. Further, using isolated human immune cells (ex vivo) we showed that ILA modulates cytokine responses in Th17 polarized cells – namely it increased IL-22 production in a dose and AhR-dependent manner. IL-22 is a cytokine important for protection of mucosal surfaces, e.g. it affects secretion of antimicrobial proteins, permeability and mucus production 7. Further, we tested ILA in LPS/INFγ induced monocytes (ex vivo), and found that ILA was able to decrease the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12p70, in a manner dependent upon both AhR and the Hydroxycarboxylic Acid (HCA3) receptor, a receptor expressed in neutrophils, macrophages and monocytes and involved in mediation of anti-inflammatory processes 8,9. Overall, our data reveal potentially important ways in which bifidobacteria influence the infant’s developing immune system.

Figure 1 – HMO-utilizing Bifidobacterium species produce immuno-regulatory aromatic lactic acids in the infant gut.

Our study provided a novel link between HMO-utilizing Bifidobacterium species, production of aromatic lactic acids and immune-regulation in early life (Figure 1). This may explain previous observations that the relative abundance of bifidobacteria in the infant gut is inversely associated with development of asthma and allergic diseases 10–12 and our results, together with other recent findings13–15 are pointing towards aromatic lactic acids (especially ILA) as potentially important mediators of beneficial immune effects induced by HMO-utilizing Bifidobacterium species.

References

- Laursen, M. F. et al. Infant Gut Microbiota Development Is Driven by Transition to Family Foods Independent of Maternal Obesity. mSphere 1, e00069-15 (2016).

- Laursen, M. F., Bahl, M. I., Michaelsen, K. F. & Licht, T. R. First foods and gut microbes. Front. Microbiol. 8, (2017).

- Zelante, T. et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 39, 372–385 (2013).

- Sridharan, G. V. et al. Prediction and quantification of bioactive microbiota metabolites in the mouse gut. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–13 (2014).

- Laursen, M. F. et al. Bifidobacterium species associated with breastfeeding produce aromatic lactic acids in the infant gut. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1367–1382 (2021).

- Sakanaka, M. et al. Varied pathways of infant gut-associated Bifidobacterium to assimilate human milk oligosaccharides: Prevalence of the gene set and its correlation with bifidobacteria-rich microbiota formation. Nutrients 12, 71 (2020).

- Keir, M. E., Yi, T., Lu, T. T. & Ghilardi, N. The role of IL-22 in intestinal health and disease. J. Exp. Med. 217, (2020).

- Peters, A. et al. Metabolites of lactic acid bacteria present in fermented foods are highly potent agonists of human hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008145 (2019).

- Peters, A. et al. Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3 and GPR84 – Two metabolite-sensing G protein-coupled receptors with opposing functions in innate immune cells. Pharmacol. Res. 176, (2022).

- Fujimura, K. E. et al. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat. Med. 22, 1187–1191 (2016).

- Stokholm, J. et al. Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of asthma in childhood. Nat. Commun. 9, 141 (2018).

- Seppo, A. E. et al. Infant gut microbiome is enriched with Bifidobacterium longum ssp. infantis in Old Order Mennonites with traditional farming lifestyle. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 76, 3489–3503 (2021).

- Meng, D. et al. Indole-3-lactic acid, a metabolite of tryptophan, secreted by Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis is anti-inflammatory in the immature intestine. Pediatr. Res. 88, 209–217 (2020).

- Ehrlich, A. M. et al. Indole-3-lactic acid associated with Bifidobacterium-dominated microbiota significantly decreases inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 20, 357 (2020).

- Henrick, B. M. et al. Bifidobacteria-mediated immune system imprinting early in life. Cell 184, 3884-3898.e11 (2021).