FDA/NIH Public Workshop on Science and Regulation of Live Microbiome-based Products: No Headway on Regulatory Issues

September 20, 2018

By Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD, Executive Science Officer, ISAPP

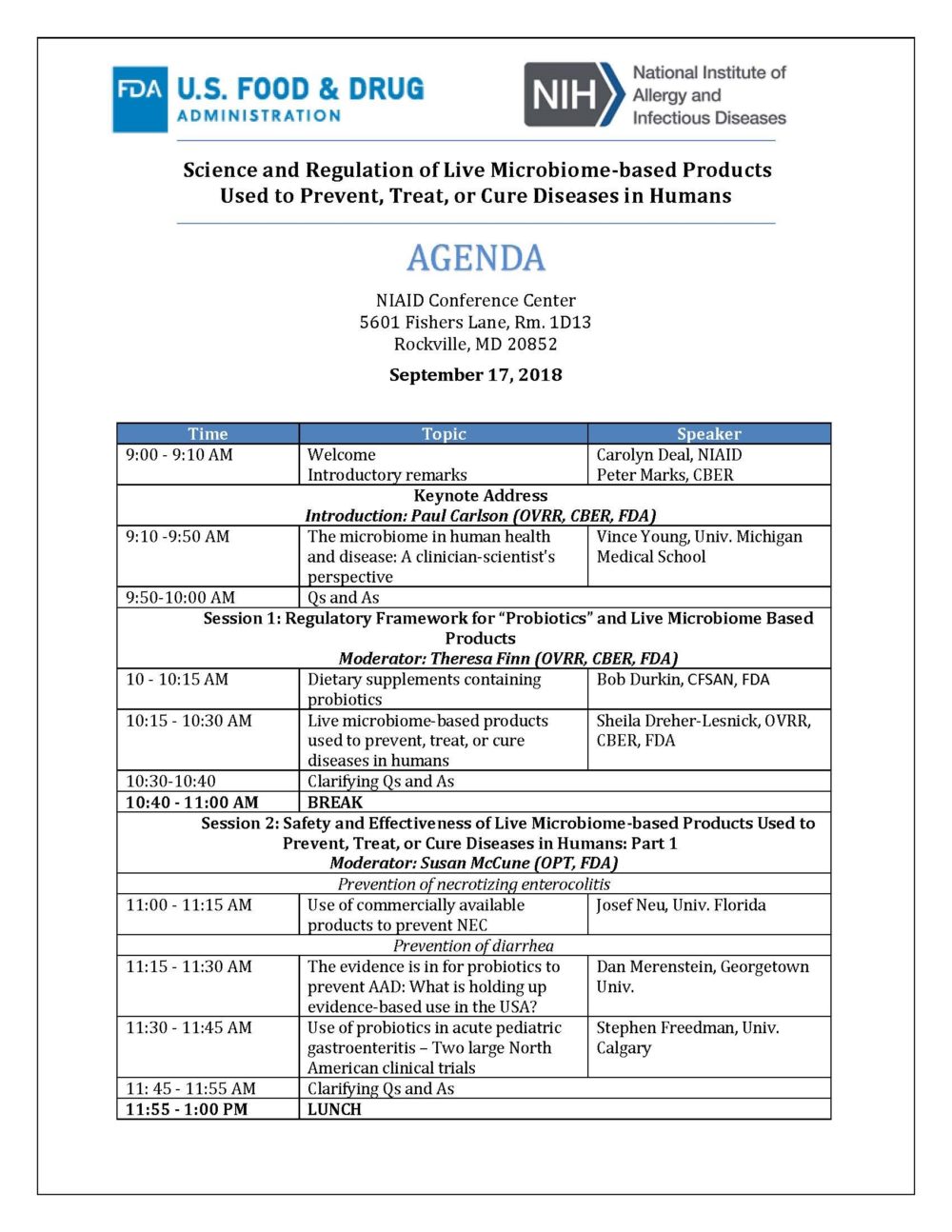

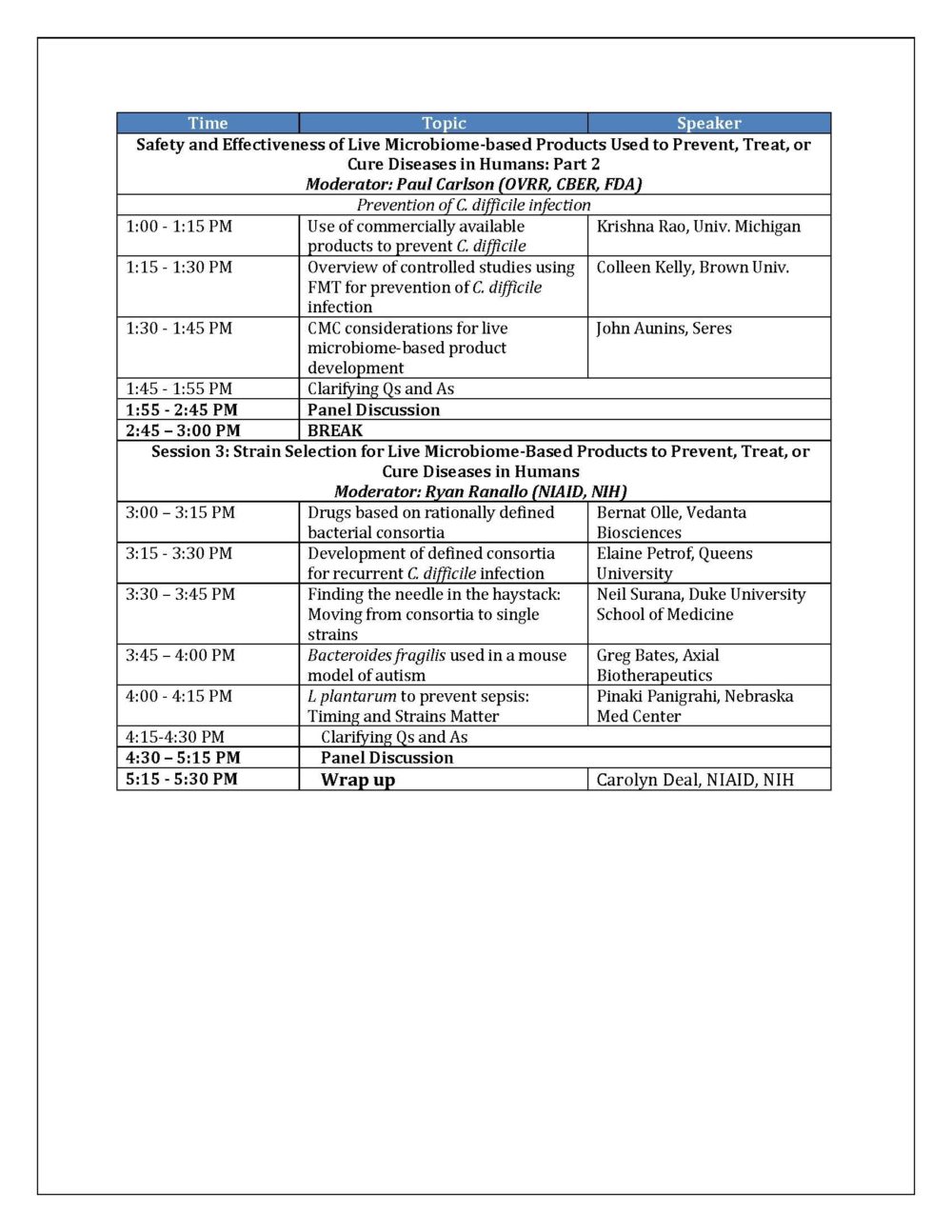

On September 16, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) collaborated on the organization of a public workshop on “Science and Regulation of Live Microbiome-based Products Used to Prevent, Treat, or Cure Diseases in Humans”. I was present at this meeting along with ISAPP vice-president, Prof. Daniel Merenstein MD, who lectured on the topic of probiotics and antibiotic-associated diarrhea.

Prof. Dan Merenstein speaking at CBER/NIAID conference

While regulatory issues are often discussed at other microbiome conferences, the fact that this meeting was organized by the FDA suggested it was a unique opportunity for some robust discussions and possible progress on regulatory issues involved with researching and translating microbiome-targeted products. The regulatory pathways to drug development seem clear enough, but regulatory issues for development of functional foods or supplements are less clear. Jeff Gordon and colleagues have previously pointed out regulatory hurdles to innovation of microbiota-directed foods for improving health and preventing disease (Greene et al. 2017), and at the 2015 ISAPP meeting, similar problems were discussed (Sanders et al. 2016).

The meeting turned out to be mostly about science. Some excellent lectures were given by top scientists in the field (see agenda below), but discussion about regulatory concerns was a minimal component of the day. Questions seeding the panel discussions focused on research gaps, not regulatory concerns: an unfortunate missed opportunity.

Bob Durkin, deputy director of the Office of Dietary Supplements (CFSAN), left after his session ended, suggesting he did not see his role as an important one in this discussion. One earlier question about regulatory perspectives on prebiotics led him to comment that the terms ‘probiotic’ and ‘prebiotic’ are not defined. From U.S. legal perspective he is correct, as there are no laws or FDA regulations that define these terms. But from a scientific perspective, such a statement is disappointing, as it shows the lack of recognition by U.S. regulators of the widely cited definitions developed by top researchers in these fields and published in 2014 and 2017, respectively.

Two issues not addressed at this meeting will require clarification from the FDA:

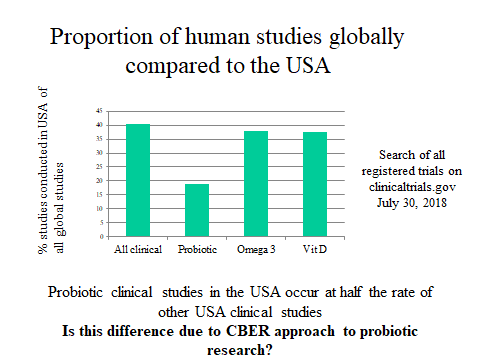

The first is how to oversee human research on foods or dietary supplements. CBER’s oversight of this research has meant most studies are required to be conducted under an Investigational New Drug (IND) application. From CBER’s perspective, these studies are drug studies. However, when there is no intent for research to lead to a commercial drug, the IND process is not relevant. Even if endpoints in the study are viewed as drug endpoints by CBER, there should be some mechanism for CFSAN to make a determination if a study fits legal functions of foods, including impacting the structure/function of the human body, reducing the risk of disease, or providing dietary support for management of a disease. When asked about this, Durkin’s reply was that CFSAN has no mechanism to oversee INDs. But the point was that without compromising study quality or study subject safety, it seems that FDA should be able to oversee legitimate food research without forcing it into the drug rubric. CBER acknowledged that research on structure/function endpoints is exempt from an IND according to 2013 guidance. But FDA’s interpretation of what constitutes a drug is so far-reaching that it is difficult to design a meaningful study that does not trigger drug status to them. For example, CBER views substances that are given to manage side effects of a drug, or symptoms of an illness, as a drug. Even if the goal of the research is to evaluate a probiotic’s impact on the structure of an antibiotic-perturbed microbiota, and even if the subjects are healthy, they consider this a drug study. With this logic, a saltine cracker eaten to alleviate nausea after taking a medication is a drug. Chicken soup consumed to help with nasal congestion is a drug. In practice, many Americans would benefit from a safe and effective dietary supplement which they can use to help manage gut disruptions. But in the current regulatory climate, such research cannot be conducted on a food or dietary supplement in the United States. There are clearly avenues of probiotic research that should be conducted under the drug research oversight process. But for other human research on probiotics, the IND process imposes research delays, added cost, and unneeded phase 1 studies, which are not needed to assure subject safety or research quality. Further, funders may choose to conduct research outside the United States to avoid this situation, which might explain the low rate of probiotic clinical trials in the United States (see figure).

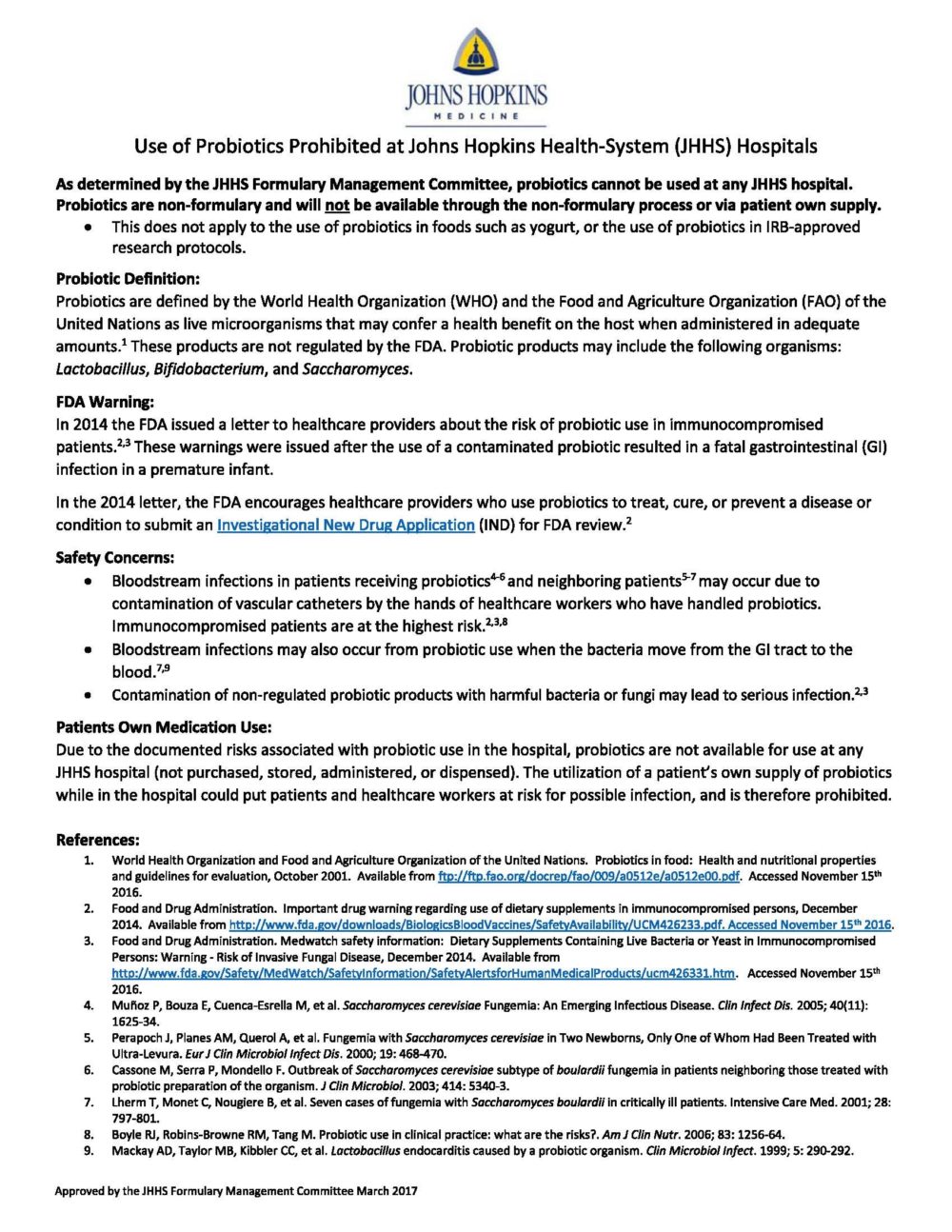

The second issue focuses on actions by CBER that have stalled evidence-based use of available probiotic products. This issue was discussed by Prof. Merenstein in his talk. He pointed out that after the tragic incident that led to an infant’s death from a contaminated probiotic product (see here; and for a blog post on the topic, see here), CBER issued a warning (here) that stated that any probiotic use by healthcare providers should entail an IND. This effectively halted availability of probiotics in some hospital systems. For example, at Johns Hopkins Health-system Hospitals, the use of probiotics is now prohibited (see below). Patients are not allowed to bring their own probiotics into the hospital out of concern for the danger this poses to other patients and staff. This means that a child taking probiotics to maintain remission of ulcerative colitis cannot continue in the hospital; an infant with colic won’t be administered a probiotic; or a patient susceptible to Clostridium difficile infection cannot be given a probiotic. Available evidence on specific probiotic preparations indicates benefit can be achieved with probiotic use in all of these cases, and denying probiotics can be expected to cause more harm than benefit.

It might be an unfortunate accident of history that probiotics have been delivered in foods and supplements more than drugs. The concept initially evolved in food in the early 1900’s, with Metchnikoff’s observation that the consumption of live bacilli in fermented milk had value for health. Probiotics have persisted as foods through to the modern day, likely because of their safety. The hundreds of studies conducted globally, including in the U.S. until 10-15 years ago, were not conducted as drug studies, even though most would be perceived today as drug studies by CBER. This has not led to an epidemic of adverse effects among study subjects. True, serious adverse events have been reported, but the overall number needed to harm due to a properly administered probiotic is negligible.

According to its mission, the FDA is “…responsible for advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medical products more effective, safer, and more affordable and by helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medical products and foods to maintain and improve their health.” Forcing human research on products such as yogurts containing probiotics to be conducted as drug research, when there is no intent to market a drug and when the substances are widely distributed commercially as GRAS substances, does not advance this mission. Further, CBER actions that discourage evidence-based use of available probiotics keeps effective and safe products out of the hands of those who can benefit.

A robust discussion on these issues was not part of the meeting earlier this week. Researchers in the United States interested in developing probiotic drugs will find CBER’s approaches quite helpful. Yet researchers interested in the physiological effects of, or clinical use of, probiotic foods and supplements will continue to be caught in the drug mindset of CBER. CFSAN does not seem interested. But without CFSAN, human research on, and evidence-based usage of, probiotic foods and supplements will continue to decline (see figure), to the detriment of Americans.

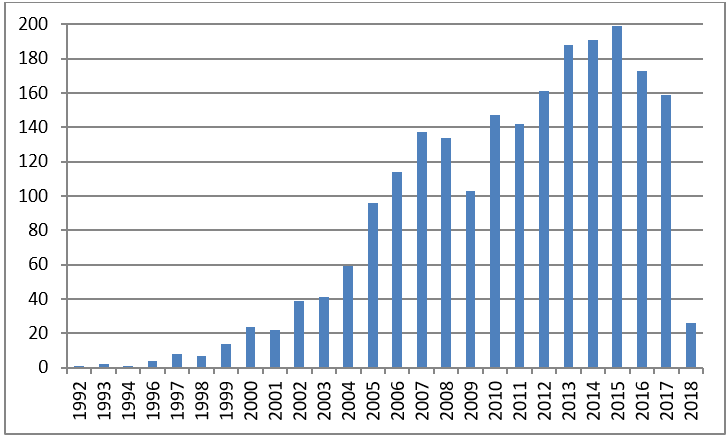

Human clinical trials on “probiotic”

1992-September 20, 2018