Episode 27: Investigating the benefits of live dietary microbes

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

The Science, Microbes & Health Podcast

This podcast covers emerging topics and challenges in the science of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics and fermented foods. This is the podcast of The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), a nonprofit scientific organization dedicated to advancing the science of these fields.

Investigating the benefits of live dietary microbes, with Prof. Colin Hill PhD and Prof. Dan Tancredi PhD

Episode summary:

In this episode, the ISAPP podcast hosts themselves are the experts: Prof. Colin Hill PhD from APC Microbiome Ireland / University College Cork and Prof. Dan Tancredi PhD from University of California – Davis talk about their recent work investigating the health benefits from consuming higher quantities of live dietary microbes – and not just microbes that meet the probiotic criteria.

Key topics from this episode:

- Profs. Hill and Tancredi were involved with others in a recent series investigations & 3 published papers on whether there should be a recommended daily intake of live microbes.

- Prof. Hill started by writing a blog, prompted by the finding that meta-analyses on probiotics tended to show some general benefits for health. Would this apply to any safe, live microbes – even those that do not meet the probiotic criteria?

- Various hypotheses (hygiene hypothesis, old friends hypothesis, missing microbes hypothesis) posit that a lack of microbes is associated with poorer health.

- Clean water and clean food have reduced the burden of infectious disease. But at the same time, across populations there has been an increase in chronic diseases. Could a lack of live dietary microbes be contributing to this increase in chronic disease, because the immune system lacks adequate inputs? Or in other words, could there be a general health benefit for healthy people in consuming high quantities of live microbes?

- To address the hypothesis scientifically: they investigated the health status of people who eat large vs. small numbers of safe live microbes in their diets. Starting with NHANES data in the US, the researchers classified foods into categories of high / medium / low numbers of live microbes.

- Note that not all fermented foods contain live microbes, but some contain high numbers of live microbes. A possible confounding factor in the analysis was that high microbe foods tend to be healthier foods.

- The researchers published a series of 3 papers. The 3rd paper showed an association between intake of live microbes and various (positive) measurements of health. Consistent, modest improvements were seen across a range of health outcomes.

- This is an association, but statistically the team did use regression analysis to statistically adjust for effects on health that could be due to other factors besides the live microbial intake.

- The take-home is not to eat unsafe or rotten food, but rather to eat more high-microbe or fermented foods, and in general eat a healthy diet.

Episode links:

- Prof. Hill’s blog: Recommended daily allowance (RDA) for microbes?

- Paper 1: Should There Be a Recommended Daily Intake of Microbes?

- Paper 2: A Classification System for Defining and Estimating Dietary Intake of Live Microbes in US Adults and Children

- Paper 3: Positive health outcomes associated with live microbe intake from foods, including fermented foods, assessed using NHANES database

Additional Resources:

Live Dietary Microbes: A role in human health. ISAPP infographic.

About Prof. Colin Hill PhD:

Colin Hill has a Ph.D in molecular microbiology and is a Professor in the School of Microbiology at University College Cork, Ireland. He is also a founding Principal Investigator in APC Microbiome Ireland, a large research centre devoted to the study of the role of the gut microbiota in health and disease. His main interests lie in the role of the microbiome in human and animal health. He is particularly interested in the effects of probiotics, bacteriocins, and bacteriophage. In 2005 Prof. Hill was awarded a D.Sc by the National University of Ireland in recognition of his contributions to research. In 2009 he was elected to the Royal Irish Academy and in 2010 he received the Metchnikoff Prize in Microbiology and was elected to the American Academy of Microbiology. He has published more than 600 papers and holds 25 patents. More than 80 PhD students have been trained in his laboratory. He was president of ISAPP from 2012-2015.

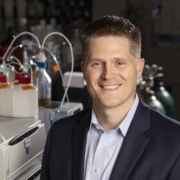

About Prof. Dan Tancredi PhD:

Daniel J. Tancredi, PhD, is Professor in Residence of Pediatrics in the University of California, Davis School of Medicine. He has over 25 years of experience and over 300 peer-reviewed publications as a statistician collaborating on a variety of health-related research. A frequent collaborator on probiotic and prebiotic research, he has attended all but one ISAPP annual meeting since 2009 as an invited expert. In 2020, he joined the ISAPP Board of Directors. Colin Hill and Daniel co-host the ISAPP Podcast Series “Science, Microbes, and Health”. On research teams, he develops and helps implement effective study designs and statistical analysis plans, especially in settings with clusters of longitudinal or otherwise correlated measurements, including cluster-randomized trials, surveys that use complex probability sampling techniques, and epidemiological research. He teaches statistics and critical appraisal of evidence to resident physicians; graduate students in biostatistics, epidemiology, and nursing; and professional scientists. Dan grew up in the American Midwest, in Kansas City, Missouri, and holds a bachelor’s degree in behavioral science from the University of Chicago and masters and doctoral degrees in mathematics from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He lives in the small Northern California city of Davis, with his wife Laurel Beckett (UC Davis Distinguished Professor Emerita), their Samoyed dogs Simka and Milka, and near their two grandkids.