By ISAPP board of directors

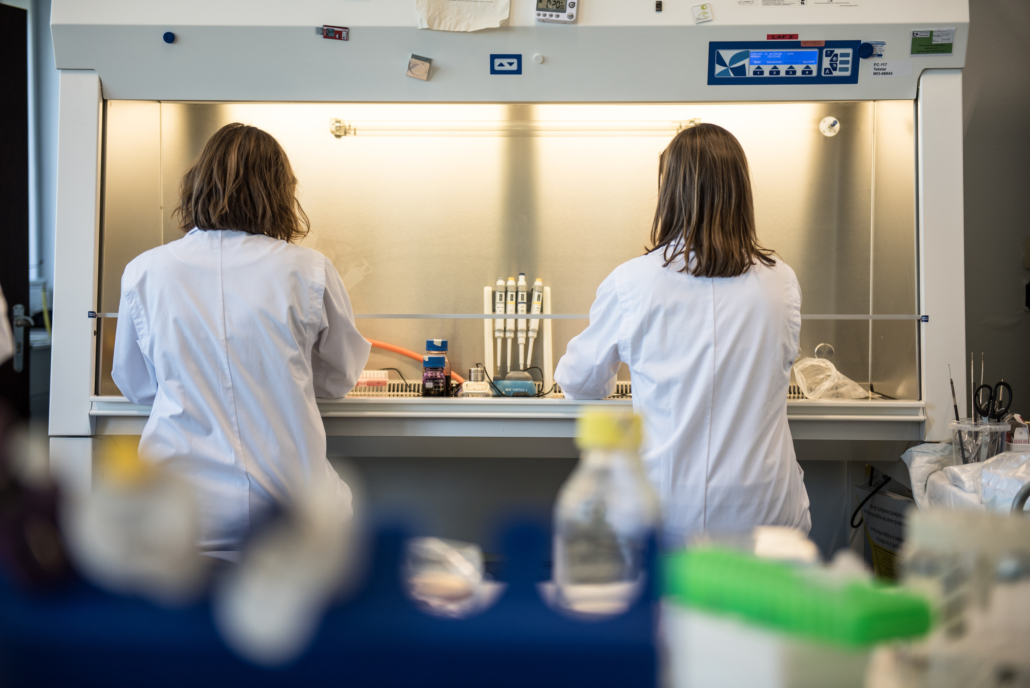

With the global spread of COVID-19, the scientific community has experienced an unusual interruption. Across every field, many laboratories are temporarily shuttered and research programs of all sizes are on hiatus. Principal investigators around the world are doing their part to keep their students and local communities safe, and many are donating lab safety equipment to medical first responders who urgently need it.

In this global circumstance of research being put on hold, it is enlightening to consider what some scientists in the fields of probiotics, prebiotics, and fermented foods are working on—or proposing—in the context of understanding ways to combat viral threats. These individuals are rising to the scientific challenge of finding effective ways to prevent or treat viral infections, which may directly or indirectly contribute to progress against SARS-CoV-2.

Here, ISAPP shares words from some of these scientists—and how they have connected the dots from probiotics to coronavirus-related work with potential medical relevance.

Prof. Sarah Lebeer, University of Antwerp, Belgium: Relevance of the airway microbiome profile to COVID-19 respiratory infection and using certain lactobacilli to enhance delivery or efficacy of vaccines

Could the microbes in our upper and lower airways play a role in how we respond to the virus? Significant individual differences exist in the microbes that are prevalent and dominant in our airways. Lactobacilli are found in the respiratory tract, especially in the nasopharynx. They might originate there from the oral cavity via the oronasopharynx, but we have found some strains that seem to be more adapted to the respiratory environment, for example by expressing catalase enzymes to withstand oxidative stress. Currently we have a Cell Reports paper in press that shows certain lactobacilli are more prevalent in the upper respiratory tract of healthy people compared to those with chronic rhinosinusitis. Further investigation of one strain found in healthy people showed it inhibited growth and virulence of several upper respiratory tract pathogens. Our work on other viruses shows that certain lactobacilli can even block the attachment of viral particles to human cells. This raises the possibility that lactobacilli could be supplemented through a local spray to help improve defenses against the inhaled virus. Based on these data, we are initiating an exploratory study with clinicians and virologists on whether specific strains of lactobacilli in the nasopharynx and oropharynx could have potential to reduce viral activity via a multifactorial mode of action, including barrier-enhancing and anti-inflammatory effects, and reduce the risk of secondary bacterial infections in COVID-19.

Another line of exploratory research from our lab pertains to the delivery or efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Currently, many groups are rapidly developing vaccines, which predominantly use the viral spike S protein or its receptor-binding domain as antigen to induce protective immunity. We are exploring the potential of specific strains of lactobacilli with immunostimulatory effects as adjuvants for intranasal SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, or the potential of a genetically engineered antigen-producing organism for vaccine delivery.

At this year’s virtual ISAPP annual meeting, Dr. Karen Scott and I will also be leading an ISAPP discussion group called “How your gut microbiota can help protect against viral infections”. We will discuss previous work that has shown bacteria can have anti-viral effects. For many years, our colleagues, Profs. Hania Szajewska and Seppo Salminen, have studied a different virus, namely rotavirus, that causes acute diarrhea in children, and have found that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (new taxonomy Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG) binds rotavirus and disables it, thereby blocking viral infection/multiplication. This may explain why this probiotic reduces the incidence and duration of acute diarrhea in children. Similar findings have been reported for specific probiotics and prebiotics and prevention of upper respiratory tract infections.

Prof. Rodolphe Barrangou, North Carolina State University, USA: Engineering probiotic lactobacilli for vaccine development

Between NC State University and Colorado State University (CSU) there is a historical collaborative effort aiming at engineering probiotics to develop novel vaccines. The intersection of probiotics and antivirals is the focus here with expressing antigens on the cell surface of probiotics to develop oral vaccines. The CSU infectious diseases center is very much fully operational and focused on COVID-19 now, and we recently received a research exception to open our lab for two individuals assigned to this NIH-funded project, and pivot our rotavirus efforts here to coronavirus. We are actively engineering Lactobacillus acidophilus probiotics expressing COVID-19 proteins to be tested as potential vaccines at CSU in the near future, as progress dictates.

Prof. Colin Hill, University College Cork, Ireland: The microbiome as a predictor of COVID-19 outcomes

We have recently proposed a project to examine oral and faecal microbiomes to identify correlations/associations between COVID-19 disease severity and individual microbiome profiles. If funded, we propose to analyse bacterial and viral components of the microbiome from three body sites (nasopharyngeal swabs, saliva, and faeces) in 200 donors and mine the data for biomarkers of disease risk and clinical severity. We will use machine learning to identify microbiome signatures in patients who contract the virus and remain asymptomatic, those who develop a mild infection, or those who have an acute infection requiring admission to an intensive care unit and intubation. This will enable microbiome-based risk stratification of subjects testing positive, and appropriate clinical management and early intervention, and prioritization of subjects for receiving an eventual vaccine.

Dr. Dinesh Saralaya, Bradford Institute for Health Research, UK: A live biotherapeutic product for targeted immunomodulation in COVID-19 infection

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an unprecedented challenge to our healthcare systems and we desperately require the rapid development of new therapies to ease the burden on our intensive care units. As well as its appropriate mechanism of action (targeted immunomodulation rather than broad immunosuppression), the highly favourable safety profile of MRx-4DP0004 makes it a particularly attractive candidate for COVID-19 patients, and may potentially allow us to prevent or delay their progression to requiring ventilation and intensive care.

The trial is a Phase II randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral Live Biotherapeutic MRx-4DP0004 in addition to standard supportive care for hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Up to 90 subjects will be randomised 2:1 to receive either MRx-4DP0004 or placebo (two capsules, twice daily) for 14 days. The primary endpoint is change in mean clinical status score as measured by the WHO’s 9-point Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement, while secondary endpoints include a suite of additional measures of clinical efficacy such as need for and duration of ventilation, time to discharge, mortality, as well as safety and tolerability. The size and design of the trial are intended to generate a meaningful signal of clinical benefit as rapidly as possible.

Drs. Paul Wischmeyer and Anthony Sung, Duke University School of Medicine, USA: Probiotics for prevention or treatment of COVID-19 infection

We are planning several randomized clinical trials of probiotics in COVID-19 prevention and treatment. These trials are based on multiple randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses that have shown that prophylaxis with probiotics may reduce upper and lower respiratory tract infections, sepsis, and ventilator associated pneumonia by 30-50%. These benefits may be mediated by the beneficial effects of probiotics on the immune system. The Wischmeyer laboratory and others have shown that probiotics, such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, can improve intestinal/lung barrier and homeostasis, increase regulatory T cells, improve anti-viral defense, and decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines in respiratory and systemic infections. These clinical and immunomodulatory benefits are especially relevant to individuals who have developed, or are at risk of developing, COVID-19. COVID-19 has been characterized by severe lower respiratory tract illness, and patients may manifest an excessive inflammatory response similar to cytokine release syndrome, which has been associated with increased complications and mortality. We hypothesize that probiotics will directly reduce COVID-19 infection risk and severity of disease/symptoms. Thus, we are proposing a range of trials, the first of which will be:

A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the PRObiotics To Eliminate COVID-19 Transmission in Exposed Household Contacts (PROTECT-EHC). Objective: Prevent infection and progression of illness in household contacts/caregivers of known COVID-19 patients exposed to COVID-19 (who have a >20-fold increased risk of infection). We will conduct a multicenter, randomized, double blind, phase 2 trial of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG vs. placebo to decrease infections and improve outcomes. This trial will include weekly collection of microbiome samples from multiple locations (i.e. fecal, oral). This trial will utilize a commercial probiotic, delivering 20 billion CFU of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, and placebo.

We are currently developing protocols to study prevention and treatment of COVID-19 in a range of other at-risk populations including: 1) Healthcare providers; 2) Hospitalized patients; 3) Nursing home and skilled nursing facilities workers. We are seeking additional funding and potential collaborators/trial sites for this work, and encourage interested funders and collaborators to reach out for further information or to join the effort at: Paul.Wischmeyer@nullduke.edu and also encourage you to follow our progress and our other probiotic/microbiome work on Twitter: @paul_wischmeyer

Prof. Gregor Reid, University of Western Ontario, Canada: Documenting anti-viral mechanisms of certain probiotic strains

While our institute is now studying the cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients, the closure of my lab has meant I have turned to surveying the literature: Prof. Glenn Gibson and I have a paper published in Frontiers in Public Health stating a case for probiotics and prebiotics to help ‘flatten the curve’ and keep patients from progressing to severe illness. There is good evidence that certain orally administered probiotic strains can reduce the incidence and severity of viral respiratory tract infections. Mechanistically this appears to be, in part, through modulation of inflammatory responses similar to those causing severe illness in COVID-2 patients, and antiviral activity — which has not been shown against SARS-Co-V2 but has been documented against common respiratory viruses, including influenza, rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus. Improving gut barrier integrity and affecting the gut-lung axis may also be part of these probiotics’ mechanism of action. At a time when drugs are being tried with little or no anti-COVID-19 data, probiotic strains documented for anti-viral, immunomodulatory and respiratory activities should be considered for clinical trials to be part of the armamentarium to reduce the burden and severity of this pandemic.

Rapid, collaborative effort

As the world waits in ‘lockdown’ mode, continued scientific progress for coronavirus prevention or treatment is critically important. ISAPP salutes all probiotic and prebiotic scientists who are stepping up to pursue unique solutions. Addressing the important research questions described above will require a rapid collaborative effort, from obtaining ethical approval and involving medical staff to collecting the samples, to recruiting participants as well as experts to process and analyze samples. All of this has to be done in record time – but from our experience of this scientific community, it’s definitely up to the challenge.