Bob Hutkins, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Department of Food Science and Technology and Leslie Delserone, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, University Libraries

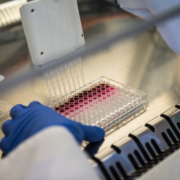

For scientists who study probiotics and prebiotics, these are exciting times. Every day, there are new discoveries and new opportunities. There certainly are many challenges – obtaining grants, recruiting and mentoring students and postdocs, editorial duties, and maintaining competitive research programs.

But perhaps the most challenging activity is keeping up with the literature. Back in our respective graduate school days, there were only a handful of journals that required regular reading (and most arrived via regular mail in print). One of us even remembers waiting for mail delivery to learn about the latest science.

There are now dozens of journals that publish high-quality papers on probiotics, prebiotics, fermented foods, gut health, and other relevant topics. No longer does one have to wait for the latest scientific report – most of us are bombarded with emailed journal highlights, tables of contents, and latest science alerts.

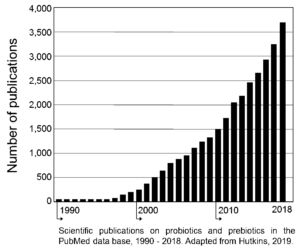

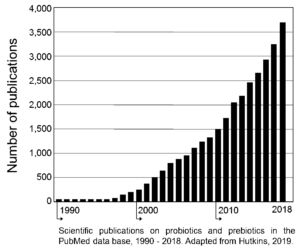

The figure below illustrates this situation. In 2001 (when ISAPP was formed), there was about 1 probiotic-oriented paper published per day. Now, with prebiotics included, there are more than ten new papers in the literature every single day!

Indeed, just since 2015, there have been more than 12,000 papers on probiotics and prebiotics listed in PubMed. Add in fermented foods, gut health, and methods papers, and those numbers will easily double or triple.

For researchers, clinicians, and other scientists, there are simply too many papers to read and digest. Thus, for better or worse, many scientists perform a literature triage of sorts, reading papers mainly from so-called high-impact journals.

As a result, probiotic and prebiotic papers published in the top journals inevitably get the most attention, whether deserved or not. An unfortunate consequence is that papers in other journals sometimes are over-looked. Perhaps that’s one reason why, based on searches of several citation indexes, about a fourth of all papers published in our field never get cited at all!

So which papers in our field attracted the most attention or had the greatest impact? Until recently, the only metrics used to assess impact were the journal’s impact factor and an article’s citation score – how many times a particular paper had been cited by other papers. This is no longer the case, as noted below. But assuming citation numbers actually reflect impact, we’ve compiled a short list of the most important papers in our field.

To do this, we used two multidisciplinary online indexes, Web of Science Core Collection (WoS) and Scopus. The WoS indexes more than 20,000 journals, while Scopus covers more than 30,000 peer-reviewed journals; we limited the WoS search to its Science Citation Index Expanded. We separately searched the terms probioti* and prebioti* in the article title, looking for papers and reviews published since 1990, and sorting the results for “times cited” or “cited by” from highest to lowest.

For probiotics, there were more than 10,000 (WoS) and 13,600 (Scopus) articles and reviews. As expected, several of the most cited papers were reviews. Surprisingly, two were reviews on use of probiotics in aquaculture. Indeed, Verschuere et al. (2000) was the second and third most cited study in WoS and Scopus, respectively. The 2014 ISAPP consensus paper (Hill et al., 2014) was the 2nd and 3rd most cited paper (Scopus and WoS respectively, with 920 and 1,034 citations as of late March 2019).

And the top probiotic paper in our field since 1990? That would be a Lancet report that described results of an RCT in which Lactobacillus GG was administered to pregnant women and newborns with atopic eczema as the clinical end-point (Kalliomäki et al., 2001). This paper garnered more than 1,500 citations within the WoS, and 1,953 as tracked by Scopus. Among the authors of this study is current ISAPP president, Seppo Salminen. Incidentally, the 4-year follow-up to that same study (Kalliomaki et al., 2003) was the 4th most cited paper in both indexes!

For prebiotics, there were more 3,000 papers listed. Leading the list of most cited papers is the seminal Gibson and Roberfroid (1995) paper in the Journal of Nutrition that “introduced the concept”. Papers by Glenn Gibson and his colleagues dominate the list of most cited prebiotic papers. But the most cited primary research paper on prebiotics was another clinical study from Finland (Kukkonen et al., 2007).

As noted above, citations are no longer the only way to measure impact. After all, clinicians, industry scientists, and government regulators and policy makers also read and apply published information. If a paper leads to a new treatment or technology, could there be a greater impact for the social good?

Consider the science paper with perhaps the greatest overall societal impact in the past 20 years. That would be Brin and Page’s 1998 paper published in what at the time was a relatively obscure journal, Computer Networks and ISDN Systems. The article began, in case you haven’t read it, with these six simple words, “In this paper, we present Google”.

Until recently, paper impacts were difficult to measure. But now we have Altmetrics, Twitter, and other ways to assess impact. Given that it usually takes at least a year before a published paper receives a citation in the WoS and Scopus environments, social media provide a way to gauge impact in real-time. Indeed, a recent editorial in Nature Cell Biology (2018) suggests that plenty of scientists embrace social media. Evidently, many use it to sort through information as quickly as their fingers can tap.

Anonymous. 2018. Social media for scientists. Nature Cell Biology 20(12): 1329. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0253-6

Brin, S., and L. Page. 1998. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 30(1-7):107-117. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X

Gibson, G.R., and M.B. Roberfroid. 1995. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. Journal of Nutrition 125(6):1401-1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401

Hill, C., F. Guarner, G. Reid, G.R. Gibson, D.J. Merenstein, B. Pot, L. Morelli, R.B. Canani, H.J. Flint, S. Salminen, P.C. Calder, and M.E. Sanders. 2014. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology 11(8):506-514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

Hutkins, R.W. 2019. Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods, 2nd ed.; Hoboken, N.J., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA

Kalliomäki, M., S. Salminen, H. Arvilommi, P. Kero, P. Koskinen, and E. Isolauri. 2001. Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 357(9262):1076-1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04259-8

Kalliomaki, M., S. Salminen, T. Poussa, H. Arvilommi, and E. Isolauri. 2003. Probiotics and prevention of atopic disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 361(9372): 1869-1871. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13490-3

Kukkonen, K., E. Savilahti, T. Haahtela, K. Juntunen-Backman, R. Korpela, T. Poussa, T. Tuure, and M. Kuitunen. 2007. Probiotics and prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharides in the prevention of allergic diseases: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 119(1):192-198. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.009

Verschuere, L., G. Rombaut, P. Soorgeloos, and W. Verstraete. 2000. Probiotic bacteria as biological control agents in aquaculture. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 64(4):655-671. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.655-671.200