By Mary Ellen Sanders PhD, executive science officer, ISAPP, and Daniel Merenstein MD, Department of Family Medicine, Georgetown University School of Medicine

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) recently published a short viewpoint that called into question the safety and efficacy of probiotics. After careful review, we concluded that some opinions expressed were not consistent with available data. We share our perspectives here.

Claim 1: The paucity of high-quality data supporting the value of probiotics.

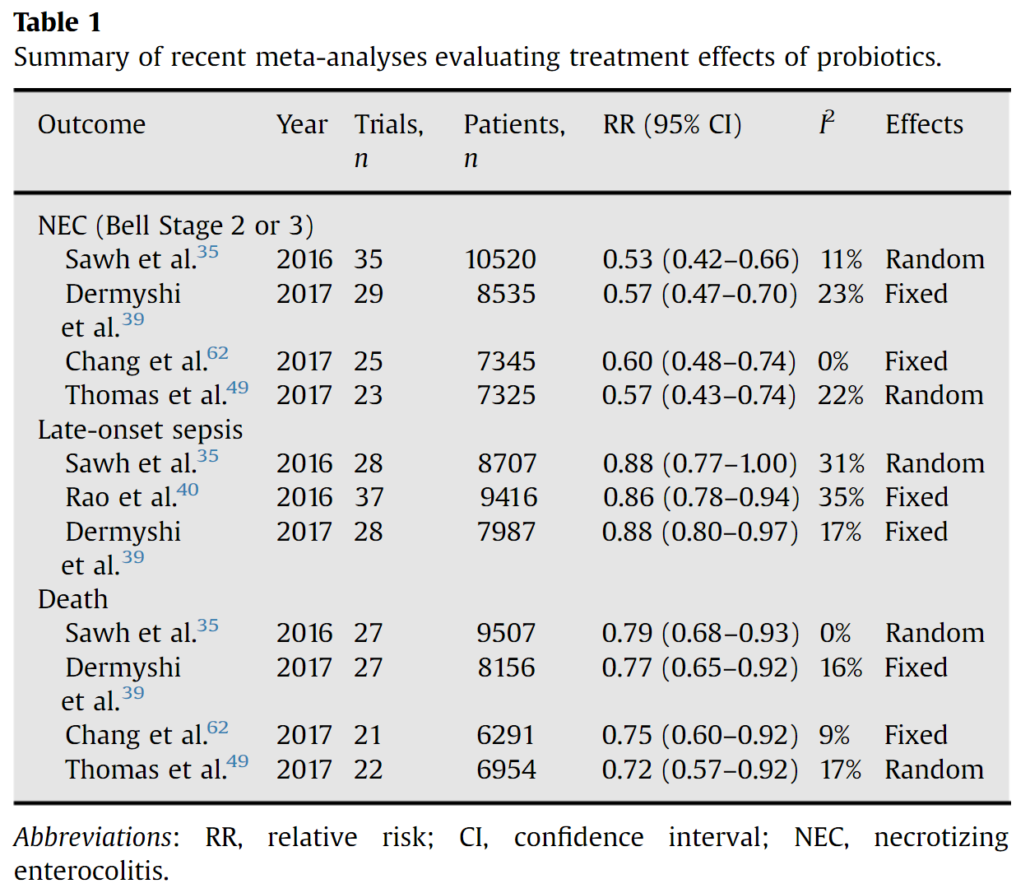

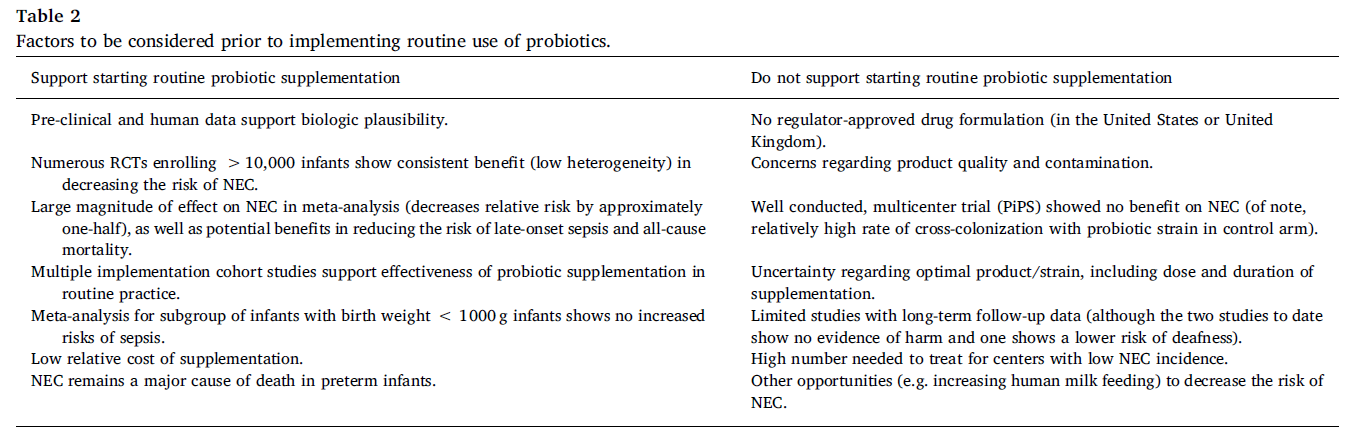

The authors speak to the “paucity” and “lack” of data supporting probiotic use. They criticize probiotic meta-analyses in general, even though there are many well-done ones, which describe clear PICOS, assess the quality of studies included, and assess publication bias. Many conclude that there is evidence that certain probiotics may be beneficial for several clinical endpoints. In the case of treatment of colic, an individual participant data meta-analysis was conducted on a single strain, and concluded “L reuteri DSM17938 is effective and can be recommended for breastfed infants with colic” (Sung et al. 2018). For necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a change in practice is recommended by a Cochrane meta-analysis (AlFaleh et al. 2018), which is consistent with draft American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommendations posted last month. In some cases, conclusions are qualified as being based on low quality data, which is also the case with many standard-of-care medical interventions. Other benefits supported for certain probiotics by evidence are shown in Table 1 of Sanders et al. 2018. But an evidence-based review of available data would not support a general statement that “data are lacking.”

Instead, we think a discussion of what evidence is actionable is reasonable to have. For this discussion, different people or groups can reasonably set the bar at different levels for what constitutes actionable evidence. But several medical organizations, including the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, World Gastroenterology Organisation, American College of Gastroenterology, AGA (proposed, for antibiotic-associated diarrhea, NEC and pouchitis), European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization, and European Society for Primary Care Gastroenterology have actionable recommendations for probiotic use for one or more indications. For those indications, any individual physician may judge that the available evidence as not convincing to him or her, but many qualified healthcare experts did find the evidence convincing and have made recommendations accordingly. We recognize that the JAMA viewpoint was limited in the number of words and references allowed, but to impugn an entire field, the authors are obliged to explain why their views differ so much from established organizations.

The authors also criticize the inclusion of small, single-center trials in probiotic meta-analyses. They state such studies have less oversight, are more susceptible to misconduct and are at greater risk of bias than larger, multicenter trials, and thereby skew conclusions of meta-analyses in favor of probiotics. They state, without evidence, that small trials are more likely to show large effects and are more likely to be published. They advocate for meta-analyses that only include multi-center trials, thereby ignoring much available evidence on the basis of unsubstantiated preferences. There are a number of reasons why some trials are multi-center, but improved quality or closer monitoring are not among them (see here, here and here). Multicenter trials may be necessary to study a rare medical endpoint, a condition with an expected small effect size but significant health implications, or to accelerate the time course for a study. In fact, an analysis of 81 meta-analyses of RCTs in 2012 concluded:

“Our results do not support prior findings of larger effects in SC (single-center) than MC (multi-center) trials addressing binary outcomes but show a very similar small increase in effect in SC than MC trials addressing continuous outcomes. Authors of systematic reviews would be wise to include all trials irrespective of SC vs. MC design and address SC vs. MC status as a possible explanation of heterogeneity (and consider sensitivity analyses).” [Emphasis ours]

In our experience, the size of a study does not inevitably minimize risk of bias. We have directly witnessed private physicians enroll for large multi-site trials without such oversight or professionalism. As the great David Sackett said in his paper from 20 years ago, “The more detailed the entry form and eligibility criteria for ‘somebody else’s’ RCT, the greater the risk the criteria will be ignored, misunderstood or misapplied by distracted clinicians who regard them as further intrusions into an overfull call schedule.” Further, due to often being underpowered, taken alone smaller studies are less, not more, likely to generate positive findings than larger trials. But when they are included in a meta-analysis, these studies contribute to the total body of evidence. We have personally worked on many single-center randomized controlled trials on probiotics. These often have monitors from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and/or the National Institutes of Health, they are all registered with both primary and secondary outcomes listed, they utilize a data safety monitoring board, they undergo true allocation concealment, and otherwise are conducted to minimize risk of bias. To criticize probiotic studies for being single-center vs multicenter seems unjustified and baseless.

It is quite true that many of the studies conducted on probiotics were done 15 or more years ago, and the quality standards do not meet what we expect today. We wholeheartedly agree but would ask the authors to review studies conducted on drugs 15 years ago, and they will see the same issues. So we agree that more trials using modern quality standards are needed in the field of probiotics, as is the case for any interventions with a long history of being studied.

Claim 2: Potentially biased reviews of probiotic efficacy

In trying to explain why physicians might recommend probiotics, the authors speculate that some professional societies and some journals may be insufficiently critical in reviewing probiotic studies due to financial conflicts of interest. We have no doubt that there is bias in the scientific realm, which is not just limited to financial conflicts of interest, but question if there is any evidence that this occurs any more or less frequently with probiotics compared to any other realm of science. To leverage this accusation at the probiotic field specifically implies it is especially egregious, but no data supporting this accusation were provided. Also there is no face validity for this accusation. There is much more money to be made by pharmaceuticals and medical interventions than probiotic supplements and yogurts.

Claim 3: Complex framework in which probiotics are regulated and sold

The regulatory framework for probiotics can be difficult to navigate and is not always in the best interest of stakeholders, but we don’t think it’s reasonable to criticize the probiotic field for this situation. In the USA, probiotic products are bound by law that was enacted by Congress and the rules/guidance developed by the FDA for allowable product claims, levels of required regulatory oversight, and lack of requirements for premarket approval. It is fair to criticize Congress and the FDA for these circumstances surrounding the category of dietary supplements, but doing this in the context of an article on probiotics unfairly maligns probiotics.

Drugs vs dietary supplements. Most probiotics are sold as foods or dietary supplements. Since probiotics were first described as fermenting microbes in soured milk, this makes historical sense. Companies and consumers do not view these products as drugs, and in most cases they are not used as drugs. Outside a regulatory mindset, it makes perfect sense for foods to be useful for promoting health and managing symptoms, and this is what has driven 30 years of research and marketing of probiotics. Forcing all probiotics into a drug rubric would deprive consumers of access, would greatly increase their cost, and would preclude responsible food/supplement manufacturers from producing them. Drugs are drugs primarily to protect the safety of the patient. All drugs are assessed with a risk/benefit balance, and in some cases, the risk is significant. In the case of probiotics, we agree with the authors that most probiotics are likely safe for the general population. We see no reasonable justification to advocate that these products must all be researched and sold as drugs.

Probiotic product quality.The authors seem to prefer the drug model for probiotics based on a perceived need for improved product quality and oversight. Yet all foods and dietary supplements in the USA are required by law to be manufactured under good manufacturing practices. This includes most every product bought at the grocery store and served for dinner as well as probiotic foods and supplements. Further, companies are required to label their products in a truthful and not misleading fashion, including representations of contents and claims. Companies that fail to meet these standards are in violation of the law. Yes, there are products – of all types – that fall short of these requirements. The many responsible probiotic manufacturers and probiotic scientists decry such occurrences. However, these cases do not define the probiotic field any more than medical errors define physicians. It is not fair to impugn the entire probiotic industry based on the ‘bad apples’ that participate in it. A 2017 ESPGHAN review cites surveys of probiotic products from different regions globally, most of which report examples of probiotic products falling short in some quality attribute. Such surveys highlight quality problems, but due to sampling and methodological approaches, their results do not provide a reliable estimate of the extent of problem among commercial probiotic products. Many probiotic products are produced responsibly and are subjected to third party quality audits. The absence of such third party documentation is not evidence of poor quality, but we agree that it serves to improve consumer and healthcare provider confidence (see Jackson et al. 2019), and if more fully adopted, would weed out irresponsible probiotic manufacturers.

Oversight of probiotic research. The authors state, “If a manufacturer claims that any product, including a probiotic, cures, mitigates, treats, or prevents disease, the product is classified as a drug, thereby triggering a costly Investigational New Drug (IND) application process.” However, they seem to conflate the regulatory approach to product claims and the regulatory oversight of biologic drug research. In the case of product claims, if a product claims to cure, treat, prevent or mitigate disease, it is by definition a drug. If it has not undergone appropriate drug approval process, it is an illegally marketed drug and is subject to FDA action, including recall. Probiotics not destined for sale as drugs should not have to be researched under a drug rubric. This does NOT mean that such studies will de facto be substandard studies. We all understand the importance of conducting and reporting trials according to well-established guidelines. Studies on foods and supplements can and should follow those same principles.

Claim 4: Possible concerns about probiotic safety

Medical professionals balance potential harm with potential benefit for any intervention they recommend. Regarding safety of probiotics, the authors acknowledge that most probiotics are likely safe, but we would qualify that statement with “for their intended uses.” The use of probiotics in critically ill patient populations needs to be done with caution, proper oversight and a justification that the potential benefit will outweigh risk. The authors cite two examples to support their concern about probiotic safety, both in critically ill patient populations. One was a retrospective study looking at bacteremia in critically ill children (see the report here and responses to the report here and here). The second was a RCT that reported higher mortality in patients with pancreatitis (see the report here, with additional perspectives on interpreting safety outcomes here and here). We are not aware of any probiotics that are marketed for such uses, and if they were, they would be marketed as drugs, requiring drug-level safety and efficacy evidence. These studies are not an indictment of safety of probiotic foods and supplements, which in most cases are intended for the generally healthy population.

Medical professionals balance potential harm with potential benefit for any intervention they recommend. Regarding safety of probiotics, the authors acknowledge that most probiotics are likely safe, but we would qualify that statement with “for their intended uses.” The use of probiotics in critically ill patient populations needs to be done with caution, proper oversight and a justification that the potential benefit will outweigh risk. The authors cite two examples to support their concern about probiotic safety, both in critically ill patient populations. One was a retrospective study looking at bacteremia in critically ill children (see the report here and responses to the report here and here). The second was a RCT that reported higher mortality in patients with pancreatitis (see the report here, with additional perspectives on interpreting safety outcomes here and here). We are not aware of any probiotics that are marketed for such uses, and if they were, they would be marketed as drugs, requiring drug-level safety and efficacy evidence. These studies are not an indictment of safety of probiotic foods and supplements, which in most cases are intended for the generally healthy population.

The authors further state that studies identifying adverse events from probiotics are the “tip of the iceberg” – creating an image of a huge number of unreported adverse incidents poised to be revealed. We have personally studied the most widely used Bifidobacterium strain, and in well over 30,000 pediatric patient days have not seen any serious adverse events and no more adverse events than placebo. The article cited by the authors states that our trials adequately reported harm. Obviously, no intervention is harmless, and no one claims as much for probiotics. It is true that older probiotic studies can rightly be criticized for not rigorously collecting and reporting data on adverse events (Hempel et al. 2011). However, a reasonable assessment of all available data, including data from well-conducted clinical trials, including trials in vulnerable populations, history of safe use, FDA notified assessments for GRAS use of certain probiotic strains, European Food Safety Authority QPS list, and others support that commonly used probiotics have a strong safety record for use in the general public.

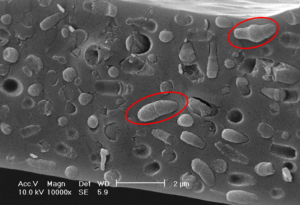

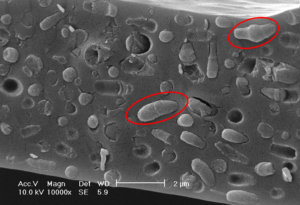

Transferable antibiotic resistance. Regarding the risk that probiotics may transfer antibiotic resistance genes, this is a hypothetical concern – there is no documented case of this. Further, one pillar of probiotic safety assessments is that strains with antibiotic resistance genes flanked by mobile genetic elements are excluded from commercialization. As stated by Ouwehand et al. 2016, “Probiotics are specifically selected to not contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance and not carry transferable antibiotic resistance.” The current approach to probiotic safety is that complete, well annotated genome sequences are available for commercial strains. This information is typically included in GRAS notices submitted to the FDA, and all the major probiotic suppliers require this level of safety assessment. This is the expected standard by the European Food Safety Authority as well, a standard that we enthusiastically and unreservedly endorse. Transferable antibiotic resistance is not a lurking threat of probiotics use, but is a well-considered issue adequately addressed by responsible probiotic manufacturers.

Conclusion

We believe that this JAMA viewpoint misrepresents the totality of data on probiotics and can potentially do harm by dissuading use of probiotics in an evidence-based manner. Important points have been raised by the authors, especially with regard to the use of probiotics in vulnerable populations, but this does not characterize most of probiotic use. We agree, as we expect the majority of scientists working on probiotics would, that additional, well controlled human studies are needed. That was why we were pleased to see the authors’ studies assessing the impact of L. rhamnosus R0011 and L. helveticus R0052 or L. rhamnosus GG on acute pediatric gastroenteritis, even though the results of both studies were null (see blog post regarding these studies here and here). But as we await additional trials, we have a responsibility to consider available evidence. The authors raise many good points that the entire medical field could learn from, but there are clear indications for probiotics and they should continue to be used for these indications, likely benefitting many while harming few.

Acknowledgements

MES and DM are grateful for the critical review of this perspective by probiotic safety expert Dr. James Heimbach, biostatistician Dr. Daniel Tancredi, and gastroenterologist and probiotic expert Dr. Eamonn Quigley.