‘Brain fogginess’ and D-lactic acidosis: probiotics are not the cause

Mary Ellen Sanders PhD, Executive Science Officer, International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics

Bruno Pot PhD, Research Group of Industrial Microbiology and Food Biotechnology, Faculty of Sciences and Bioengineering Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium

See here for ISAPP letter to the Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology editor regarding this paper.

See related post Probiotics and D-Lactic Acid Acidosis in Children

Rao and colleagues incriminated probiotics in the induction of D-lactic acidosis in their paper titled “Brain fogginess, gas and bloating: a link between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), probiotics and metabolic acidosis” (Rao et al. 2018). Eamonn Quigley MD, Bruno Pot, microbiologist and I on behalf of ISAPP authored a letter to the editor of Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology (currently In Press), summarizing many medical and other concerns with the study design, execution and conclusions.

It is regrettable that one poorly controlled paper can lead to such negative backlash on the probiotic field. Respectable media outlets including Newsweek, Science Daily, Psychology Today, the Daily Mail, MSN.com, and others blindly reported the results of this study without critical analysis of the paper. These stories advance the opinion that probiotics are potentially harmful and should be sold only as drugs. This flies in the face of many scientific studies that document safety compounded with safe, worldwide consumption for decades of probiotic foods and supplements.

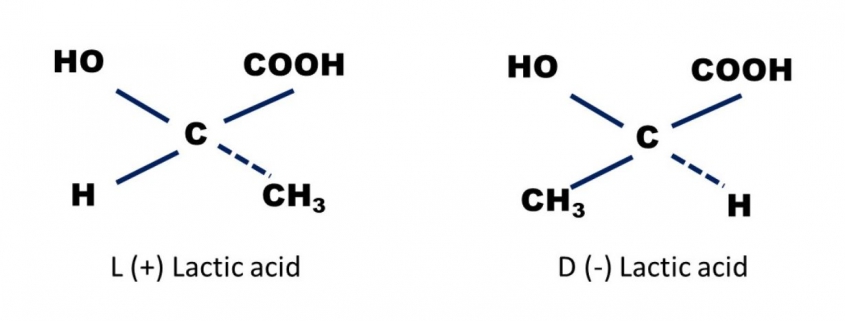

Bifidobacterium as a genus does not yield D-lactate as a metabolic end product. Some Lactobacillus species do (Table 19.1 in Pot 2014). Among common probiotic Lactobacillus species, the following are classified as species that can produce D-lactic acid: L. acidophilus, L. gasseri, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (one of the 2 yogurt starter culture bacteria), L. fermentum, L. lactis, L. brevis, L. helveticus, L. plantarum and L. reuteri. Individual strains within each species may vary with regard to levels of D-lactic acid produced.

The observational nature of the Rao et al. paper precludes any conclusive link between probiotic consumption and symptoms observed. The authors acknowledge that they have only established an association between probiotic use and the symptoms, but the misleading paper title suggests an intention to indict probiotics, even in the absence of evidence. It is much more likely that the patient population with underlying SIBO in this study sought relief from their gut symptoms by use of probiotics rather than the probiotics being the cause of their symptoms.

D-lactic acidosis is a rare but serious condition, typically occurring in people with short bowel syndrome. These patients should know that D-lactate-producing probiotics are not recommended for them. In people with a normal gut, D-lactate produced by members of the gut microbiota – including some probiotics – is metabolized by other members of the gut microbiota and does not accumulate. Thus, under normal circumstances, D-lactic acidosis does not result from consumption of D-lactic acid-producing probiotics. The patients in the Rao et al. study showed very low levels of D-lactic acid, calling into question if these SIBO patients were even acidotic. Moreover, the D-lactic acid that was present was not proven to be a result of probiotic growth. This is important, as intestinal bacteria including Escherichia coli also produce D-lactic acid. In cases of SIBO, numerous metabolites are produced in the small intestine (including alcohol), leading to a variety of SIBO symptoms, possibly including the poorly defined phenomenon of “brain fogginess”. Many issues that should have been were not addressed in the Rao et al. paper.

The real tragedy with the publication of this paper is that – similar to many such media scares in the past – it is may cause harm. The sensationalist headlines may dissuade safe probiotic use in people who can truly benefit from them. Scientists and clinical researchers – both academic and from industry – must remain diligent in assessment and reporting of any probiotic harms. However, the Rao et al. paper is not an example of this.

Reference:

Pot B. 2014. The genus Lactobacillus. Chapter 19. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Biodiversity and Taxonomy, First Edition. Edited by Wilhelm H. Holzapfel and Brian J.B. Wood. 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Other reading:

Mack D. 2004. D(-)-lactic acid producing probiotics, d(-)-lactic acidosis and infants. Canadian J Gastroenterol. 18:671-5. (ISAPP-commissioned paper)

Łukasik J, Salminen S, Szajewska H. Rapid review shows that probiotics and fermented infant formulas do not cause d-lactic acidosis in healthy children. Acta Paediatr. 2018 Aug;107(8):1322-1326. doi: 10.1111/apa.14338. Epub 2018 Apr 24.