By Dr. Gabriel Vinderola PhD, Instituto de Lactología Industrial (CONICET-UNL), Santa Fe, Argentina

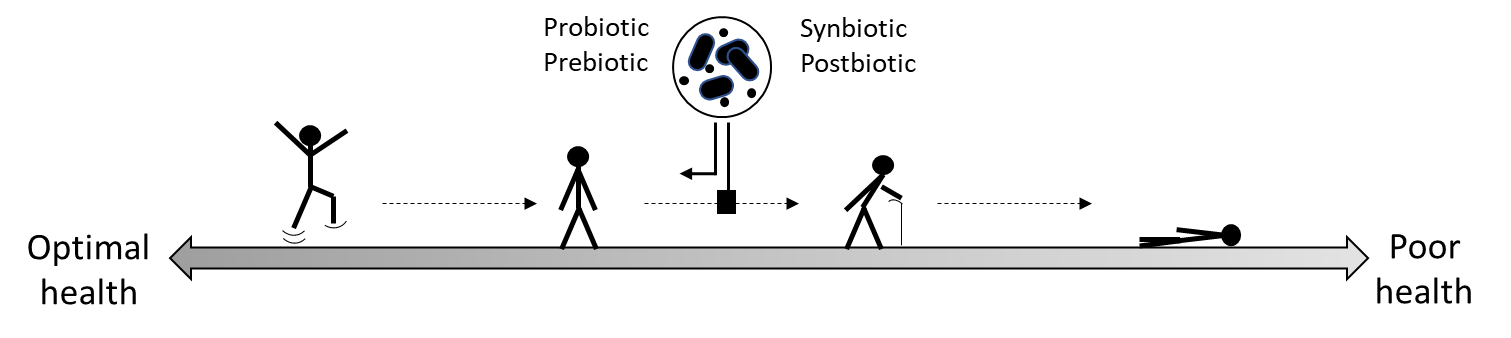

The publication of a new definition for the term “postbiotics” by ISAPP in 2021 (Salminen et al., 2021a) spurred discussion on a variety of platforms, including scientific journals, social media and in-person debates organized at industry and scientific meetings. A couple of months after the publication of the definition, a group of scientists expressed their disagreement about the new definition (Aguilar-Toalá et al., 2021), and this was followed by a reply in support of the ISAPP definition (Salminen et al., 2021b). An example of the debate on social media is reflected in this post on LinkedIn. The comments that followed the post highlighted points of disagreement and misunderstandings about the ISAPP definition. These reactions were helpful to me in preparing for panels and debates scheduled at 2023 meetings in Amsterdam, Chicago and Bratislava, discussed more fully below.

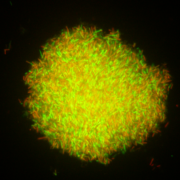

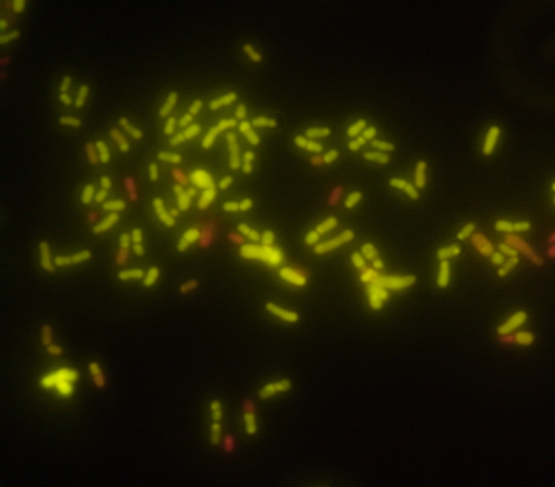

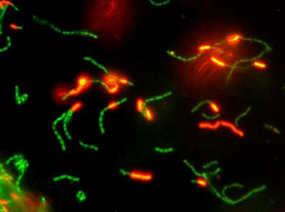

Prior to the ISAPP panel, many terms were used to refer to non-viable microorganisms that confer a health benefit when administered in adequate amounts: heat-killed probiotics, heat-treated probiotics, heat-inactivated probiotics, tyndallized probiotics, ghost-probiotics, non-viable probiotics, paraprobiotics, cell fragments, cell lysates or postbiotics. ISAPP proposed that going forward, the single term “postbiotic” be used in scientific communications, marketing, regulatory frameworks and to counter the difficulty in tracking of papers for comprehensive systematic reviews. ISAPP’s goal was to bring focus and clarity to the term postbiotic, provide criteria for proper use of the term and set the stage for future innovation in the field.

Two competing terms

When considering preparations of non-viable microorganisms that confer a health benefit, two terms seem to have emerged most dominantly:

The term paraprobiotic was coined by Taverniti and Guglielmetti (2011) and defined as non-viable microbial cells (intact or broken) or crude cell extracts (i.e. with complex chemical composition), which, when administered (orally or topically) in adequate amounts, confer a benefit on the human or animal consumer.

The term postbiotic as proposed by Salminen et al. (2021a) refers to a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.

The definition of paraprobiotics is limiting in that it does not clarify the scope for metabolites to be present alongside non-viable cells, and this may be problematic as most products of this type developed and marketed so far contain microbial metabolites along with non-viable cells. Further, the definition of paraprobiotics refers to conferring a benefit, but not a health benefit, a divergent way of conceptualizing a ‘biotic’ substance. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and as defined above, postbiotics, all stipulate the requirement of conferring a health benefit. In addition, embedding the term ‘probiotic’ into the term paraprobiotic may mislead some to conclude that a paraprobiotic is a dead probiotic, which places a significant burden on any live microbial precursor to first meet the probiotic definition.

Finally, the authors (Taverniti and Guglielmetti 2011) state in their paper: “In addition, once a health benefit is demonstrated, the assignation of a product into the paraprobiotic category should not be influenced by the methods used for microbial cell inactivation, which may be achieved using physical or chemical strategies, including heat treatment, or UV ray deactivation, chemical or mechanical disruption, pressure, lyophilisation or acid deactivation”. Since inactivation technology may have a significant impact on the functionality of a dead microbe, disassociating a paraprobiotic with the method used to inactivate the microbes makes it impossible to know if any given paraprobiotic preparation will be effective.

The definition of postbiotics by Salminen et al. (2021a) anticipates that metabolites may be optionally present in the finished product, requires a health benefit and does not suggest, at any point in the wording, that the progenitor strain of a postbiotic must be a probiotic. Further, although not explicitly stated in the definition, the supporting documentation for the proposal of this definition states that the process to make the postbiotic must be delineated specifically, the progenitor microorganism must be clearly identified and characterized and the final product must be safe for its intended use. This definition encompasses a meaningful and useful scope.

To add to the complexity of the existing landscape, prior to the ISAPP definition of postbiotics, six other definitions of the term postbiotic were proposed in the literature. While these are reviewed in detail in Salminen et al (2021b Supplementary information), many shared the commonality that their focus was bacterial byproducts or metabolites.

Questions about the ISAPP definition of postbiotic

A common question is, “Why did the ISAPP panel choose the term postbiotic to refer to inactivated microbes?” In short, the word seemed most appropriate since post means ‘after’ and biotic means ‘life’. Further, the panel recognized that although microbial metabolites might contribute to the health benefit conferred by a postbiotic, a preparation containing metabolites alone could be encompassed by a different term. Further, such metabolites (to the extent they are purified from the microbes that produce them) are readily referred to by their chemical names. Microbial metabolites may be present in a postbiotic preparation, but they are not required. The core of the definition of postbiotics is non-viable microbes, either as whole intact cells, disrupted cells or cell fragments. The life termination technology used to manufacture a postbiotic preparation should be stipulated. It cannot be assumed that heat inactivation, radiation, high pressure or any other technology will necessarily render an equally functional inanimate microbe.

Why use the descriptor “inanimate”? This is another common question. This word – meaning lifeless – reflects that the microorganisms should be dead, non-viable, no longer able to grow, to replicate, or, from an applied point of view, to form visible colonies in an enumeration medium or to be detected as live cells in flow cytometry techniques. It was preferred over the term “inactivated” only to call attention to the fact that postbiotics must confer a health benefit and in that sense, are active. For all practical purposes, non-viable can be used as an appropriate synonym.

Questions arise also about the breadth of definition, with concerns that “anything can be a postbiotic”. But broadness of a definition should not be seen as a disadvantage, as long as the limits to the definition are clear. Any microorganisms may be used as a postbiotic, as long as the identity is provided to the strain level, a life termination process is deliberately applied and safety and efficacy are demonstrated in a trial in the target host. Further, a postbiotic is not simply a dead probiotic. A probiotic is shown to confer a health benefit alive and it cannot be assumed that this property is retained when it is dead. Clearly, not anything can be a postbiotic.

Reflections on three recent conferences where the concept of postbiotics was debated

The first debate took place at the Beneficial Microbes conference in Amsterdam in November 2022. The outcomes were reported in a previous blog.

The second panel discussion took place in Chicago, at the Probiota 2023 conference in mid-June. After my talk, an audience poll was taken. Seventy-six out of around 250 attendees voted by an app in their cell phones to the question, How do you define a postbiotic? 68% selected the ISAPP definition, 9% said postbiotics were metabolites produced by probiotics, 4% chose the option “metabolites produced by the gut microbiota”, 14% said “none of the above” (I was curious to know what it would be for them), whereas 4% were not sure. Thus, the ISAPP definition was preferred by the majority. It is interesting to note the composition of the panel debate: three industry representatives and myself. Two of the companies represented presently market products referred to as postbiotics and containing non-viable microbes, whereas for the third company, postbiotics are “molecules created by bacteria”, according to their webpage. A discrepancy in the industry towards what postbiotics are was embodied on the stage. The preference for these meeting participants for the term postbiotic over the term paraprobiotic could be deduced from the meeting program, as the first term was mentioned 56 times, while the second had not one entry.

At Probiota 2023, an officer from Health Canada announced that the regulatory body will start considering the term postbiotics, which was defined in his presentation using the ISAPP definition. As for the quantification units for postbiotics, he indicated that milligrams would be considered currently, although he anticipated the development of more refined methodologies. The topic of what and how to quantify postbiotics is a commonly heard question. I intend to lead a Discussion Group on this topic comprising academic and ISAPP member company representatives at the 2024 ISAPP meeting July 9-11 in Cork, Ireland. If you are an academic expert or an industry member interested in joining the discussion, please reach out to me at gvinde@nullfiq.unl.edu.ar.

Panel discusson on postbiotics at the Bratislava International Probiotic Conference, 2023

A third panel discussion took place late in June in Bratislava at the 16th edition of the International Probiotic Conference. Before the debate, presentations were made by Arthur Ouwehand (IFF Health, Finland), Wilbert Sybesma (Yoba For Life Foundation, The Netherlands) and Eva Armengol (AB-BIOTICS, Spain). These speakers presented examples of postbiotics as they perceived them, which in all cases referred to administered non-viable microbes, in most cases containing microbial metabolites, thereby fitting the ISAPP definition. The fourth speaker, Simone Guglielmetti, proposed separate terms for non-viable microbes, which he proposed to call paraprobiotics, and for metabolites, which he proposed to call postbiotics, according to previous definitions (Taverniti and Guglielmetti, 2011; Tsiliringi and Rescigno, 2013).

There was also a sense of agreement that definitions should encompass current science but not unduly restrict future innovation. Some examples of products presently available in the market that contain non-viable microbes, and have efficacy studies with a clinical endpoint or biomarker enhancement, are:

| Species or strain/s |

Composition |

Reference |

| B. bifidum MIMBb75 |

Heat inactivated bacteria |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32277872/ |

| Akkermansia muciniphila |

Heat inactivated bacteria |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31263284/ |

| L. fermentum CNCM MA65/4E-1b and L. delbrueckii CNCM MA65/4E-2z |

Heat inactivated bacteria plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33281937/ |

| B. breve C50 and S. thermophilus 065 |

Heat inactivated bacteria plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32629970/ |

| Aspergillus oryzae |

Heat inactivated fungi plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33742039/ |

| L. paracasei MCC1849 |

Heat inactivated bacteria plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33787390/ |

| L. sakei proBio65 |

Bacterial lysate plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32949011/ |

| S. cerevisiae |

Heat inactivated yeasts plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21501093/ |

| Vitreoscilla filiformis |

Bacterial lysate plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34976852/ |

| Mixture of pathogens |

Bacterial lysate plus metabolites |

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34976852/ |

These ten examples of commercial products based on non-viable microbes all fit the definition of postbiotics conceptualized by Salminen et al. (2021). Only the first two fit the Taverniti and Guglielmetti (2011) definition, as these contain just non-viable microorganisms, without metabolites. This may suggest that products in the current marketplace are best described by the Salminen et al. (2021) concept, which encompasses products based on non-viable microbes, which may or may not also contain microbial metabolites.

Conclusions

In conclusion, I suggest that the term postbiotic and the definition of Salminen et al. (2021a) be used for non-viable microbes (with or without metabolites) able to confer a health benefit, as reflected by the present state of the art and products developed and marketed. If deemed useful by the field, there is room yet for a new term to encompass products developed with microbial metabolites only (devoid of cells). If we consider definitions that mutually exclude non-viable microbes or metabolites, then the vast majority of products present today in the market would not be covered, as most of them deliver non-viable microorganisms and metabolites simultaneously. My overall sense after attending the Chicago and Bratislava meetings is that the meaning of the term postbiotic as mentioned by speakers, included in the meeting programs, seen in posters (future products) and in commercial products presented in booths, refers to the ISAPP definition of non-viable microbes. Time will tell how this term and definition evolves and if a broader consensus can be reached.

References

Aguilar-Toalá, J. E., Arioli, S., Behare, P., Belzer, C., Berni Canani, R., Chatel, J. M., D’Auria, E., de Freitas, M. Q., Elinav, E., Esmerino, E. A., García, H. S., da Cruz, A. G., González-Córdova, A. F., Guglielmetti, S., de Toledo Guimarães, J., Hernández-Mendoza, A., Langella, P., Liceaga, A. M., Magnani, M., Martin, R., … Zhou, Z. (2021). Postbiotics – when simplification fails to clarify. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 18(11), 825–826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00521-6

Salminen, S., Collado, M. C., Endo, A., Hill, C., Lebeer, S., Quigley, E. M. M., Sanders, M. E., Shamir, R., Swann, J. R., Szajewska, H., & Vinderola, G. (2021a). The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 18(9), 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00440-6

Salminen, S., Collado, M. C., Endo, A., Hill, C., Lebeer, S., Quigley, E. M. M., Sanders, M. E., Shamir, R., Swann, J. R., Szajewska, H., & Vinderola, G. (2021b). Reply to: Postbiotics – when simplification fails to clarify. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 18(11), 827–828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00522-5

Taverniti V, Guglielmetti S. The immunomodulatory properties of probiotic microorganisms beyond their viability (ghost probiotics: proposal of paraprobiotic concept). Genes Nutr. 2011 Aug;6(3):261-74. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0218-x. Epub 2011 Apr 16. PMID: 21499799; PMCID: PMC3145061.

Tsilingiri K, Rescigno M. Postbiotics: what else? Benef Microbes. 2013 Mar 1;4(1):101-7. doi: 10.3920/BM2012.0046. PMID: 23271068.