I have IBS – should I have my microbiome tested?

By Prof. Eamonn Quigley, MD. The Methodist Hospital and Weill Cornell School of Medicine, Houston

I am a gastroenterologist and specialize in what is referred to as “neurogastroenterology” – a rather grandiose term to refer to those problems that arise from disturbances in the muscles or nerves of the gut or in the communications between the brain and the gut. Yes, the gut has its own nervous system – as elaborate as the spinal cord – which facilitates the two-way communication between the brain and gut.

The most common conditions that I deal with are termed functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) among which irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most frequent. I have cared for IBS sufferers and been involved in IBS research for decades. But while much progress has been made, IBS continues to be a frustrating problem for many sufferers. No, it will not kill you, but it sure can interfere with your quality of life. Dietary changes, attention to life-style issues (including stress) and some medications can help but they do not help all sufferers all of the time. It is no wonder, therefore, that sufferers look elsewhere for relief. Because, symptoms are commonly triggered by food, there are a host of websites and practitioners offering “food allergy” testing even though there is minimal evidence that food allergy (which is a real problem, causes quite different symptoms and can be fatal) has anything to do with IBS. Nevertheless, sufferers pay hundreds of dollars out of pocket to have these worthless tests performed.

Now as I sit in clinic I am confronted by a new phenomenon – microbiome testing. I cringe when a patient hands me pages of results of their stool microbiome analysis. Has their hard-earned money been well spent? The simple answer is no. Let me explain. First, our knowledge of the “normal” microbiome is still in evolution so we can’t yet define what is abnormal – unless it is grossly abnormal. Second, we have learned that many factors, including diet, medications and even bowel habit can influence the microbiome. These factors more than your underlying IBS may determine your microbiome test results. Third, while a variety of abnormalities have been described in the microbiome in IBS sufferers, they have not been consistent. Someday we may identify a microbiome signature that diagnoses IBS or some IBS subgroups – we, simply, are not there yet. Indeed, our group, together with researchers in Ireland and the UK, are currently involved in a large study looking at diet, microbiome and other markers in an attempt to unravel these relationships in IBS.

There have been a lot of exciting developments in microbiome research over the past few years. One that has caused a lot of excitement comes from research studies showing that the microbiome can communicate with the brain (the microbiome-gut-brain axis). It is not too great a leap of faith to imagine how such communications could disturb the flow of signals between and brain and the gut and result in symptoms that typify IBS. We also know that some antibiotics and probiotics can help IBS sufferers. Indeed, about 10% of IBS suffers can date the onset of their symptoms to an episode of gastroenteritis (so-called post-infection IBS). All of this makes it likely that the microbiome has a role in IBS; what we do not know is exactly how. Is the issue a change in the microbiome? Is it how we react to our microbiome? Is it the bacteria themselves or something that they produce? Could our microbiome pattern predict what treatments we will respond to? These are fascinating and important questions which are being actively studied. In the meantime, I feel that microbiome testing in IBS (unless conducted as part of a research study) is not helpful.

Related Reading:

Microbiome analysis: hype or helpful?

Why microbiome tests are currently of limited value for your clinical practice

Here’s the poop on getting your gut microbiome analyzed

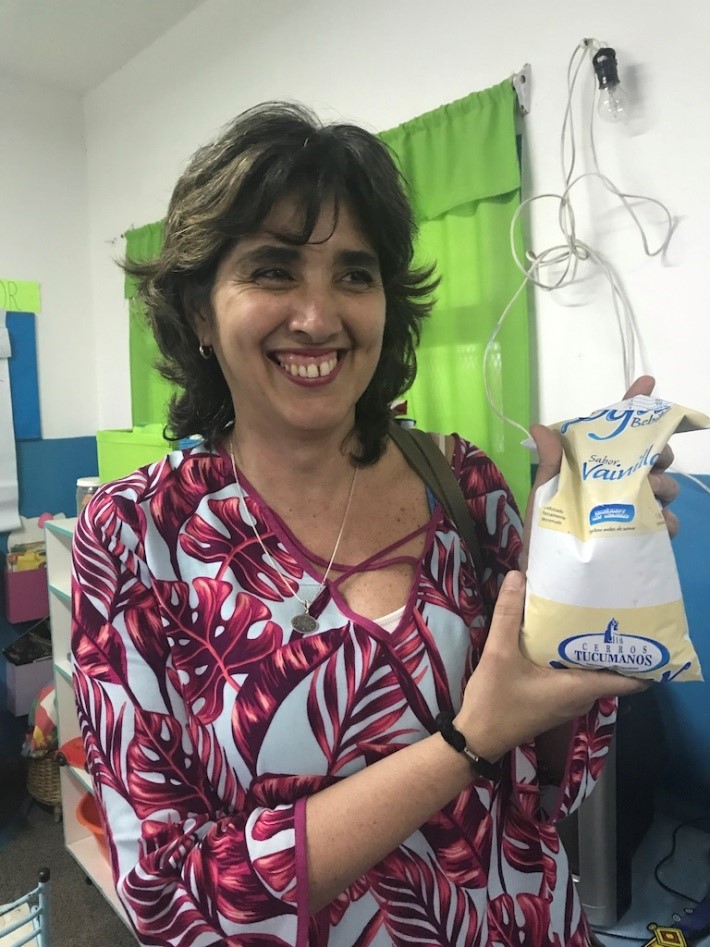

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina

Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina