By Kristina Campbell, Prof. Colin Hill PhD, Prof. Sarah Lebeer PhD, Prof. Maria Marco PhD, Prof. Dan Merenstein MD, Prof. Hania Szajewska MD PhD, Prof. Dan Tancredi PhD, Prof. Kristin Verbeke PhD, Dr. Gabriel Vinderola PhD, Dr. Anisha Wijeyesekera PhD, and Marla Cunningham

Biotic science is an active field, with over 6,600 scientific papers published in the past year. The scientific work that emerged in 2023 covered many diverse areas – from probiotic mechanisms of action to the use of biotics in clinical populations. In parallel with the scientific advancements, consumer interest in gut health and biotics is at an all-time high. A recent survey showed that 67 percent of consumers are familiar with the concept of probiotics and 51 percent of those who consume probiotics do so with the aim of supporting gut health.

Several ISAPP-affiliated experts took the time to reflect on 2023 and identify the most important directions in the fields of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fermented foods. Below are these experts’ picks for the top developments in biotic science and application during the past year.

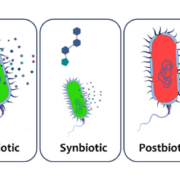

Increased recognition of biotics as a category

After ISAPP’s publication of the recent synbiotics and postbiotics definitions in 2020-2021, board members and others began referring to probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics collectively as “biotics”. 2023 has seen the term being used more widely (for example, in article headlines and communications from major organizations) to refer to these substances as a broad group.

Steps forward and steps back in the regulation of live microbial interventions

The actions of regulators have a profound impact on how biotic science is applied and how products can reach consumers. On the positive side, 2023 heralded the regulatory approval of two live microbial drug products for recurrent C. difficile infection by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Both products are derived from fecal samples, but one is delivered to the patient gastrointestinal (GI) tract by enema, and the other is delivered orally.

Meanwhile, a case of fatal bacteremia in a preterm infant who had been given a probiotic product prompted the FDA to issue a warning letter to healthcare practitioners about probiotics in preterm infants, as well as warning letters to two probiotic manufacturers. These actions had the concerning effect of reducing access to probiotics for this population, despite the accumulated evidence that probiotics effectively prevent necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. As outlined in ISAPP’s scientific statement on the FDA’s actions, the regulatory decision weighting the risks of commission over omission did not reflect the wealth of evidence for probiotic efficacy in this population and the low risk of harm.

Wider awareness of the postbiotic concept and definition

Scientific discussions on postbiotics continued throughout 2023, with several debates and conference sessions devoted to discussion of the postbiotic concept – including the status of metabolites in the definition. According to ISAPP board member Dr. Gabriel Vinderola PhD, who was a co-author on the definition paper and an active participant in many of these debates, the ISAPP definition is gaining traction and the debates have been useful in pinpointing further areas of clarification for the sake of regulators and other stakeholders. As shared with the audience at Probiota Americas 2023 in Chicago, Health Canada became the first regulatory agency to address the definition, and has started considering the term postbiotics under the ISAPP definition.

Advances in technologies for analyzing different sites in the digestive tract

When studying how biotics interface with the host via the gut microbiota, the science has relied mainly on analysis of fecal samples, with the majority of the GI tract remaining a ‘black box’. But a 2023 paper by Shalon et al., which was discussed at the ISAPP meeting in Denver, describes a device able to collect intestinal samples from different regions in the GI tract. Analysis of the metabolites and microbes indicated clear regional differences, as well as marked differences between samples in the GI tract versus fecal samples (for example, with respect to bile acids); an accompanying paper revealed novel insights into diet and microbially-derived metabolites. Efforts are underway across the world to develop smart pills or robotic pills that take samples all along the GI tract. Some devices have sensors that immediately signal to a receiver and others have been engineered to release therapeutic contents. Although these technologies may need more validation before they are useful in research or clinical contexts, they may greatly expand knowledge of the intestinal microbial community and how it interacts with biotic substances.

First convincing evidence linking intake of live microbes with health benefits

When an ISAPP discussion group in 2019 delved into the question of whether a higher intake of safe, uncharacterized live microbes had the potential to confer health benefits, it spurred a program of scientific work to follow. Efforts of this group in subsequent years led to the publication of an important study in 2023: Positive Health Outcomes Associated with Live Microbe Intake from Foods, Including Fermented Foods, Assessed using the NHANES Database. Researchers analyzed data from a large US dietary database and found clear but modest health benefits associated with consuming higher levels of microbes in the daily diet.

The benefits of live dietary microbes are being explored further in the scientific literature (for example, here, here, and here) and are likely to remain an exciting topic of study in the years ahead, building evidence globally for the health benefits of consuming a higher quantity of live microbes.

Increased interest in candidate prebiotics

Polyphenols have long been studied for their health benefits, but newer evidence suggests they may have prebiotic effects, achieving their health benefits (in part) through interactions with the gut microbiota. A theme at conferences and in the scientific literature has been the use of polyphenols to modulate the gut microbiota for specific health benefits. More than a dozen reviews on this topic were published in 2023, and several of them focused on how polyphenols may achieve health benefits in very specific conditions, such as diabetes or inflammatory bowel disease.

Another substrate receiving much attention for its prebiotic potential are human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). HMOs, found in human milk, support a nursing infant’s health by encouraging the growth of beneficial gut microbes. Several articles in 2023 have delved into the mechanisms of HMO metabolism by the gut microbiota, and explored its potential as a dietary intervention strategy to improve gut health in adults.

Sharper focus on evidence for the health and sustainability benefits of fermented foods

Fermented foods are popular among consumers, despite only early scientific knowledge on whether and how they might confer health benefits (see ‘First convincing evidence linking intake of live microbes with health benefits’, above). ISAPP board member Prof. Maria Marco PhD co-authored a review led by Dr. Paul Cotter PhD in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology on the GI-related health benefits of fermented foods. The paper clearly lays out the potential mechanisms under investigation and identifies gaps to be addressed in the ongoing study of fermented foods.

As calls for reducing carbon footprints continue across the globe, plant-based fermented foods are being singled out as an area for innovation and expansion. One example of how these foods are being explored is through the HealthFerm project, a 4-year, 13.1 million Euro project involving 23 partners from 10 countries, which is focused on understanding how to achieve more sustainable, healthy diets by leveraging fermented foods and technologies.

Novel findings related to lactic acid bacteria

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are some of the most frequently-studied microbial groups, but scientists have only begun to uncover the workings of this diverse group of bacteria and how they affect a variety of hosts. These bacteria are used as probiotics and are often beneficial members of human and animal microbiomes, and they are also essential to making fermented foods. This year marked the first ever Gordon Research Conference on LAB in California, USA. Attendees showcased the diversity of research on lactic acid bacteria, and the meeting was energized by the early investigators present and by the interest in LAB in other disciplines including medicine, ecology, synthetic biology, and engineering. One example of a scientific development in this area was the further elucidation of the mechanism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum’s extracellular electron transfer.

Progress on the benefits and mechanisms of action for probiotics to improve the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapies

Researchers have known for several years that the gut microbiota can be a determinant of the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy drugs that involve immune checkpoint blockade, but interventions that target the gut microbiota to improve response to immunotherapies have been slower to develop. This year saw encouraging progress in this important area, with probiotic benefits and mechanisms of action being demonstrated in several papers. Two of the most highly cited probiotics papers of the year centered on this topic: one showing how a tryptophan metabolite released by Limosilactobacillus reuteri (formerly Lactobacillus reuteri — see this ISAPP infographic) improves immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy, and another paper that reviewed how gut microbiota regulates immunity in general, and immune therapies in particular.

Updated resource available on probiotics and prebiotics in gastroenterology

This year the World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) guidelines on probiotics and prebiotics were updated to reflect the latest evidence, with contributions from ISAPP board member Prof. Hania Szajewska MD PhD and former board member Prof. Francisco Guarner MD PhD. The guideline lists indications for probiotic and prebiotic use, and how the use of these substances may differ in pediatric versus adult populations. Find the guideline here.