Clarifying the role of metabolites in the postbiotic definition

By Dr. Gabriel Vinderola PhD, Instituto de Lactología Industrial (CONICET-UNL), Faculty of Chemical Engineering, National University of Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina and and Prof. Colin Hill PhD, School of Microbiology and APC Microbiome Ireland, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

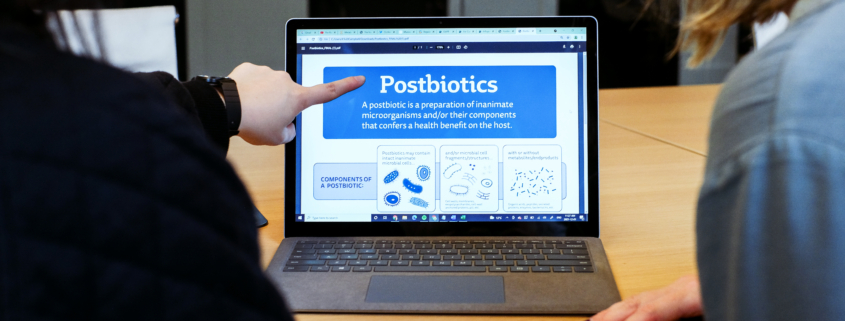

ISAPP published a definition for the term postbiotics in 2021 that states that “a postbiotic is a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host” (Salminen et al., 2021). This 19-word definition had to distill the content of the accompanying article that ran to over 9,000 words (not including references) and so obviously a lot of nuance was lost. A reading of the full paper should dispel any misconceptions, but we thought it might be timely to discuss what is perhaps the most common misunderstanding.

Some of the previous definitions included metabolites (purified or semi-purified) under the postbiotic concept. We did not agree with this interpretation. For us, the term postbiotics refers to preparations that consist largely of intact microbial cells, or preparations that retain some or all of the microbial biomass contained in microbial cells. This latter concept was captured in the phrase “and/or their components” The first column of page 3 of Salminen et al., 2021 elaborates on this; “The word ‘components’ was included because intact microorganisms might not be required for health effects, and any effects might be mediated by microbial cell components, including pili, cell wall components or other structures. The presence of microbial metabolites or end products of growth on the specified matrix produced during growth and/or fermentation is also anticipated in some postbiotic preparations, although the definition would not include substantially purified metabolites in the absence of cellular biomass. Such purified molecules should instead be named using existing, clear chemical nomenclature, for example, butyric acid or lactic acid”. So, taken in context, the scope of the ISAPP definition covers inanimate, dead, non-viable microbes; either as intact whole dead cells or in the form of “their components”. We do not consider microbial metabolites to be postbiotics. Such an interpretation would, for example, make butyrate or other end-products of fermentation postbiotics (once shown to have a health benefit). The ISAPP definition does not exclude the likelihood that microbial metabolites will be present in a postbiotic preparation, but it does require that dead microbes or microbial cell fragments or structures should be present to qualify as a postbiotic.

Why did the ISAPP definition exclude purified or semi-purified metabolites in the absence of cellular components? We fully accept that metabolites or other microbe-generated functional ingredients such as lactate, butyrate, bacteriocins, defensins, neurotransmitters, and similar compounds can be present in a postbiotic preparation. But as you can see from this list, these compounds already have names that are clearly understood. The ISAPP definition of postbiotics focuses on the beneficial role of inanimate microbes and/or their components, a category that did not have a clear definition. Postbiotics are simply one category of substances that provide microbe-associated health benefits. In terms of semantics, dictionaries define the prefix ‘post’ as meaning ‘after’ and the word ‘biotic’ as meaning ‘living things’, and so a postbiotic in that context is something that was living and is now after-life, or inanimate. Metabolites are derived from living things, but never had an independent ‘life’ of their own. As a thought experiment, let us imagine a microbe that has been shown to have a health benefit and therefore qualifies as a probiotic. If the same microbe is inactivated and continues to show a health benefit, this new formulation is no longer a probiotic and qualifies as a postbiotic. If this postbiotic preparation can be further purified and it is shown that a metabolite or metabolites in the absence of cells or their components can provide the same health benefit it ceases to be a postbiotic and becomes a health-promoting metabolite. We could imagine microbially-produced vitamins as an example.

Ideally, definitions should be clear without supplemental explanation. But short, simply worded definitions that describe complex concepts must be read in a context. There is a background, they have a scope, there are things that are covered by that definition and things that are not, and of course definitions have their limitations. It would be hard, if not impossible, to include the scope, the background, the coverage and the limitations in a 19-word definition. For instance, the 15-word probiotic definition is “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” (Hill et al, 2014). This does not include the idea that probiotics are strain-dependent, a fact that is widely accepted by the field. Other criteria for probiotics not stated in the definition include the fact that that they may be of any regulatory category, that their health benefits must be demonstrated in well-controlled trials in the target host, and that they must be safe (Binda et al. 2020).

In closing, we believe that the postbiotic concept can be an incredibly important scientific, regulatory and commercial concept. That is why we spent the time and effort to arrive at what we hope is a workable definition. We accept that the definition is not perfect but we do think it is useful, and we urge those interested in the future of this important field to read the accompanying paper carefully and to place the definition in its proper context.

See ISAPP’s Postbiotics infographic here.