Misleading press about probiotics: ISAPP responses

By Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD, Executive Science Officer, ISAPP

It seems over the last couple of years, open season on “probiotics” has been declared. Responding in a scientifically accurate fashion to misleading coverage, whether it is in reputable scientific journals or in the lay media, takes time and care.

I want to be clear: well-conducted clinical trials, regardless of the outcomes, are welcome contributions to the body of evidence. No one expects that every probiotic will work for every indication. Null trials document this – they tell researchers to look elsewhere for solutions. Further, we must acknowledge the limitations and weaknesses of available evidence; unfortunately, not all trials are well-conducted. We also need to be just as diligent in criticizing press that is overly positive about probiotic benefits, which are not backed by evidence.

However, articles with misleading information are all-too-frequently published. Below are ISAPP responses to some of these stories.

- A paper on rhamnosus GG bacteremia in ICU patients led to headlines about ‘deadly infections’ and probiotic administration ‘backfiring’, even though no patients died and clinical outcomes were not collected. ISAPP responded to clarify appropriate context for understanding the safety issues raised from this paper. See Lactobacillus bacteremia in critically ill patients does not raise questions about safety for general consumers.

- The Wall Street Journal published an article condemning probiotics for reducing fecal microbial diversity. ISAPP responded with a blog Those probiotics may actually be helping, not hurting, pointing out the errors in the author’s thinking (equating diversity with gut health).

- A pair of well-conducted clinical trials that did not show impact of probiotics on pediatric acute diarrhea led to some ignoring all previous evidence and concluding that no probiotics were useful for acute pediatric diarrhea. ISAPP responded about the importance of putting new evidence in the context of the totality of evidence: L. rhamnosus GG for treatment of acute pediatric diarrhea: the totality of current evidence. Also, Dr. Eamonn Quigley, an ISAPP board member, published an independent response.

- Pieter Cohen concluded that evidence for probiotic safety is insufficient in an article in JAMA Internal Medicine. ISAPP’s response was published in a letter to the editor, along with Cohen’s response to our letter.

- Responding to two papers in Cell (here and here), and accompanying media coverage that called into question probiotic safety and efficacy, ISAPP published a detailed post Clinical evidence and not microbiota outcomes drive value of probiotics objecting to conclusions, and released a public statement.

- Jennifer Abbasi wrote a critical article about probiotics with the inflammatory title “Are Probiotics Money Down the Toilet? Or Worse?” ISAPP responded with the following blog post: Probiotics: Money Well-Spent For Some Indications.

- When Rao, et al incriminated probiotics as a cause of D-lactic acidosis, ISAPP posted a blog and published a letter to the editor of Clin Transl Gastroenterol objecting to this conclusion.

- ISAPP responded to a paper claiming that probiotics were unsafe in children: Probiotics and D-lactic acid acidosis in children and Brain Fogginess and D-Lactic Acidosis: Probiotics Are Not the Cause.

Board member and Professor Colin Hill wrote a blog post called Another day, another negative headline about probiotics? His post provides some useful questions to consider when reacting to a publication:

- Is the article describing an original piece of research and was it published in a reputable, peer-reviewed journal?

- What evidence is there that the strain or strain mix in question is actually a probiotic? Does it fit the very clear probiotic definition?

- Was the study a registered human trial? How many subjects were involved? Was it blinded and conducted to a high standard?

- What evidence was presented of the dose administered and was the strain still viable at the time of administration?

- Were the end points of the study clear and measurable? Are they biologically or clinically significant to the subjects?

- Did the authors actually use the words contained in the headline? “Useless”, or “waste of money”, etc?

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was more somewhat daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), who liked to make stuff and sell it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the ‘staff’ of a new company.

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was more somewhat daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), who liked to make stuff and sell it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the ‘staff’ of a new company.

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob with the idea it would contain fermented maize. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob with the idea it would contain fermented maize. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

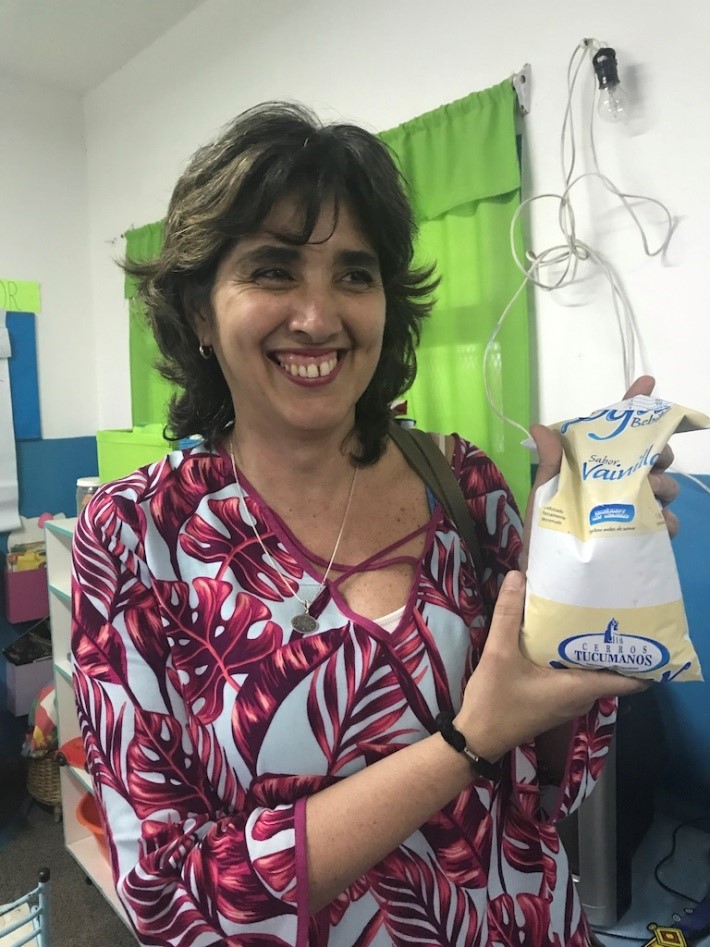

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product

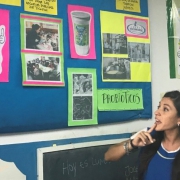

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina

Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina