Kristina Campbell, MSc, and Prof. Dan Tancredi, PhD, Professor of Pediatrics, UC Davis School of Medicine and Center for Healthcare Policy and Research

Twenty years ago, in 2002, the first ISAPP meeting was held in London, Canada. At the time, the field was much less developed: only small human trials on probiotics or prebiotics had been published, no Nutrition and Health Claims legislation existed in the EU, and the human microbiome project hadn’t been conceived.

Now in ISAPP’s 20th year, the scientific landscape of probiotics and prebiotics is vastly different. For one thing, probiotics and prebiotics now form part of the broader field of “biotics”, which also encompasses both synbiotics and postbiotics. Hundreds of trials on biotics have been published, regulations on safety and health claims has evolved tremendously globally, and ”biotics” are go-to interventions (both food and drug) to modulate the microbiota for health.

At the ISAPP annual meeting earlier this year, scientists across academia and industry joined together for an interactive session discussing the past, present and future of the biotics field. Three invited speakers set the stage by covering some important advancements in the field. Then session chair (Prof. Daniel Tancredi) invited the participants to divide into 12 small groups to discuss responses to a set of questions. The session was focused on generating ideas, rather than achieving consensus.

The following is a summary of the main ideas generated about the past, present and future of the biotics field. Many of the ideas, naturally, were future-focused – participants were interested in how to move the field of biotics forward with purpose.

The past 20 years in the biotics field

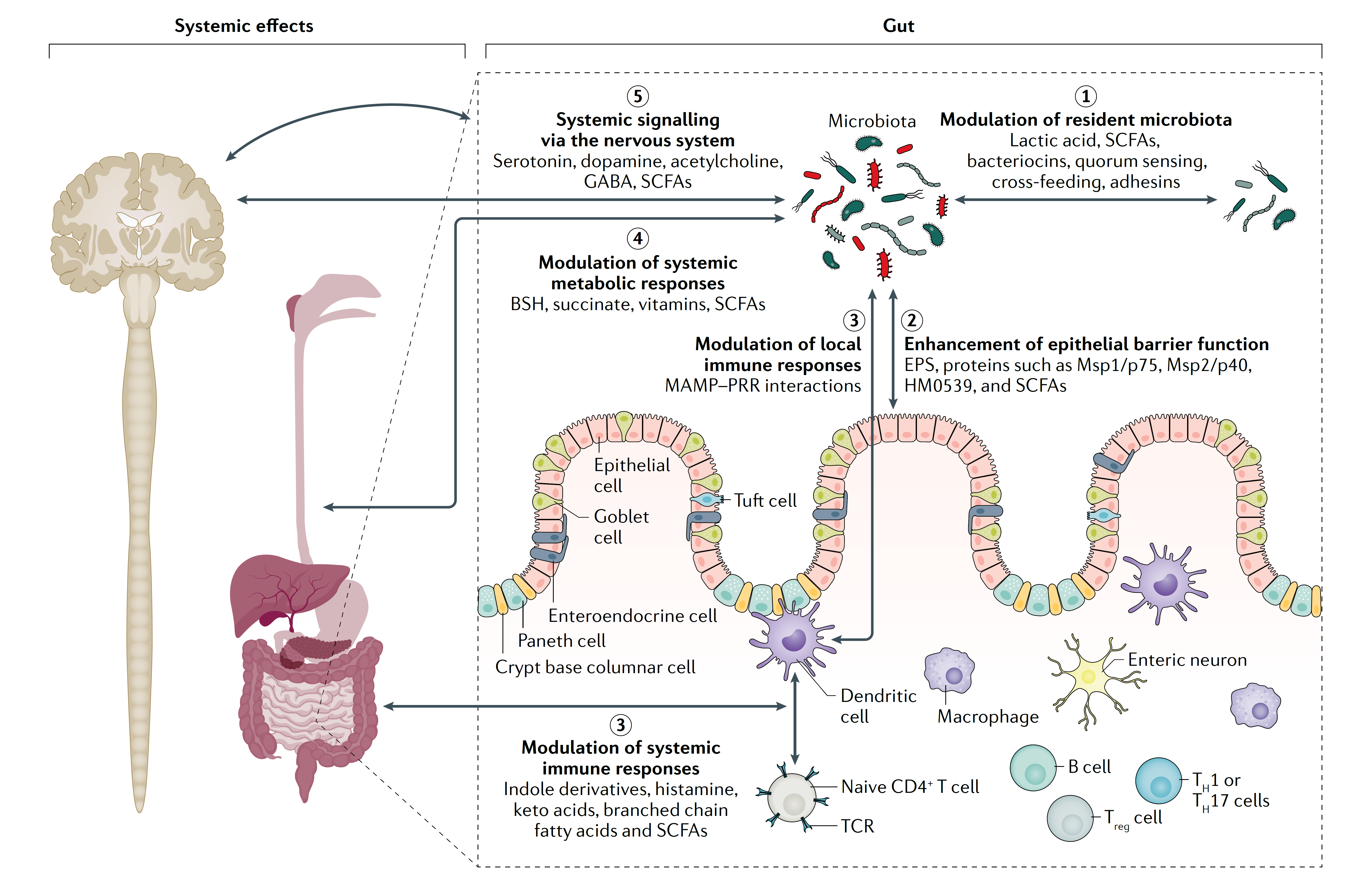

Prof. Eamonn Quigley had the challenge of opening the discussion about the past by summing up the last 20 years in the biotics field. He covered early microbiological progress in the biotics field, such as the production of antimicrobials and progress in understanding the biology of lactic acid bacteria and their phages. In the modern era, scientists made strides in understanding the role of gut bacteria and metabolites in hepatic encephalopathy; the role of C. difficile in pseudo-membranous colitis; and in the 90s, the concept of bacterial translocation in the intestines. Prof. Quigley summarized the progress and challenges in advancing the underlying science and in developing actionable clinical evidence. He noted that more high-quality clinical trials are being published lately.

Prof. Eamonn Quigley had the challenge of opening the discussion about the past by summing up the last 20 years in the biotics field. He covered early microbiological progress in the biotics field, such as the production of antimicrobials and progress in understanding the biology of lactic acid bacteria and their phages. In the modern era, scientists made strides in understanding the role of gut bacteria and metabolites in hepatic encephalopathy; the role of C. difficile in pseudo-membranous colitis; and in the 90s, the concept of bacterial translocation in the intestines. Prof. Quigley summarized the progress and challenges in advancing the underlying science and in developing actionable clinical evidence. He noted that more high-quality clinical trials are being published lately.

The discussion participants noted the following achievements in the field over the past two decades:

Recognition that microbes can be ‘good’. A massive shift in public consciousness has taken place over the past 20 years: the increased recognition that microorganisms are not just pathogens, they have a role to play in the maintenance of health. This added impetus to the idea that consuming beneficial microbes or other biotics is desirable or even necessary.

The high profile of biotics. An increasing number of people are familiar with the basic idea of biotics. Especially for probiotics, there is a strong legacy of use for digestive health; they are also widely available to consumers all around the world.

ISAPP’s published papers. Participants appreciated the papers published as a result of ISAPP’s efforts, including the five scientific consensus definition papers. These have raised the profile of biotics and clarified important issues.

Connections between basic and clinical scientists. Collaborations between biotics scientists and clinicians have been increasing over the past two decades, leading to better questions and higher quality research. ISAPP is one of the leading organizations that provides opportunities for these two groups to interact.

These were among the challenges from the past two decades, as identified by discussion participants:

Lack of understanding among those outside the probiotic/prebiotic field. Although the science has advanced greatly over the past 20 years, some outside the biotics field continue to believe the evidence for probiotic efficacy is thin. It appears some early stereotypes about probiotics and other biotics persist, especially in some clinical settings. This also leads to consumer misunderstandings and affects how they use biotics substances.

Too many studies lacking in quality. In the past, many studies were poorly designed; and sometimes the clinical research did not follow the science. Further, a relative lack of mechanistic research is evident in the literature.

Lack of regulatory harmony. Probiotics and other biotics are regulated in different ways around the world. The lack of harmonized regulations (for example, EFSA and FDA having different regulatory approaches) has led to confusion about how to scientifically substantiate claims in the proper way to satisfy regulators.

Lack of standardized methodologies. Many scientific variables related to biotics, such as microbiome measurements, do not have standardized methodologies, making comparability between studies difficult.

Not having validated biomarkers. The absence of validated biomarkers was noted as a potential impediment to conducting feasible clinical research studies.

The current status of the biotics field

At the moment, the biotics field is more active than ever. The industry has grown to billions of dollars per year and microbial therapeutics are in development all across the globe. The number of published pro/prebiotic papers is over 40K and the consensus definitions alone have been accessed over half a million times.

At the moment, the biotics field is more active than ever. The industry has grown to billions of dollars per year and microbial therapeutics are in development all across the globe. The number of published pro/prebiotic papers is over 40K and the consensus definitions alone have been accessed over half a million times.

Prof. Kristin Verbeke spoke at the interactive session about the biotics field at present. She noted that the field has faced the scientific reality that there is no single microbiota configuration exclusively associated with health. The current trajectory is to develop and expand systems biology approaches for understanding the taxonomic and functional composition of microbiomes and how those impact health. Scientists are increasingly making use of bioinformatics tools to improve multi-omic analyses, and working toward proving causation.

The future of the biotics field

Prof. Clara Belzer at the ISAPP 2022 annual meeting

Prof. Clara Belzer spoke on the future of the biotics field, focusing on a so-called “next-generation” bacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila. She covered how nutritional strategies might be based on improved understanding of the interplay between microbes and mucosal health via mucin glycans, and the potential for synthetic microbial communities to lead to scientific discoveries in microbial ecology and health. She also mentioned some notable citizen science education and research projects, which will contribute to overall knowledge in the biotics field.

Participants identified the following future directions in the field of biotics:

Expanding biotics to medical (disease) applications. One group discussed at length the potential of biotics to expand from food applications (for general overall health) to medical applications. The science and regulatory frameworks will drive this shift. They believed this expansion will increase the credibility of biotics among healthcare practitioners, as the health benefits will be medical-condition-specific and will also have much broader applicability.

As for which medical conditions are promising, the group discussed indications for which there are demonstrated mechanistic as well as clinical effects: atopic diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and stimulating the immune system to boost vaccine efficacy. In general, three different groups of medical conditions could be targeted: (1) common infections, (2) serious infectious diseases, and (3) chronic diseases for which drugs are currently inadequate, such as metabolic disorders, mental health disorders and autoimmune diseases.

Using biotics as adjuncts to medical treatments. An area of huge potential for biotics is in complementing existing medical treatments for chronic disease. There is evidence suggesting in some cases biotics could be used to increase the efficacy of drugs or perhaps reduce side effects, for example with proton pump inhibitors, statins, NSAIDs, metformin, or cancer drugs. Biotics are not going to replace commonly used drugs, but helping manage certain diseases is certainly within reach.

Using real-world data in studies. Participants said more well-conducted studies should be done using real world data. This seems in line with the development of citizen science projects as described by Clara Belzer and others at the ISAPP meeting. Real-world data is particularly important in the research on food patterns/dietary habits as they relate to biotics.

Considering new probiotic formulations. In some cases, a cocktail of many strains (50-60, for example) may be necessary for achieving a certain health effect. Using good models and data from human participants, it may be possible to create these multi-strain formulations with increased effects on the gut microbial ecosystem and increased efficacy.

Embracing omics technology and its advancement. Participants thought the next five years should see a focus on omics data, which allows for stratifying individuals in studies. This will also help increase the quality of RCTs.

More mechanism of action studies. Several groups expressed the importance of investing in understanding mechanisms of action for biotic substances. Such understandings can help drive more targeted clinical studies, providing a rationale for the exact type of intervention that is likely to be effective. Thus, clinical studies can be stronger and have more positive outcomes.

Increased focus on public / consumer engagement. Educational platforms can engage consumers, providing grassroots support for more research resources as well as advancing regulatory frameworks. Diagnostic tools (e.g. microbiome tests with validated recommendations) will help drive engagement of consumers. Further, science bloggers are critical for sharing good-quality information, and other digital channels can have great impact.

Defining and developing “precision biotics”. One group talked about “precision biotics” as solutions that target specific health benefits, which also have a well-defined or unique mechanism of action. At present, this category of biotics is in its very early stages; a prerequisite would be to better define the causes and pathways of gastrointestinal diseases.

Increasing incentives for good science. Participants discussed altering the regulatory and market environments so that good science and proper randomized, controlled trials on biotics are incentivized. Regulators in particular need to change their approaches so that companies are driven primarily by the science.

Precise characterization of responders and non-responders. The responder and non-responder phenomenon is seen with many biotic interventions. Across the field, deep characterization of subjects using multi-omics approaches with a high resolution is needed to determine what factors drive response and non-response to particular biotics substances.

Overall, participants’ ideas centered around the theme of leaning into the science to be able to create better-quality biotics products that support the health of different consumer and patient groups.

Special thanks to the table discussion leaders: Irene Lenoir-Wijnkoop, Zac Lewis, Seema Mody, David Obis, Mariya Petrova, Amanda Ramer-Tait, Delphine Saulnier, Marieke Schoemaker, Barry Silkington, Stephen Theis, Elaine Vaughan and Anisha Wijeyesekera.