By ISAPP Board of Directors, plus Prof. Francisco Guarner and Dr. Bruno Pot

September 10, 2018

Two recent papers have generated much adverse publicity for the probiotic field. Headlines driven by sensationalism, not data, claim “Probiotics labelled ‘quite useless’” (BBC) and “Probiotics ‘not as beneficial for gut health as previously thought’” (The Guardian). The quotes are from author Eran Elinav, who generalizes the study findings to all ‘probiotics’ as a class – a generalization that ignores that specific probiotic are meant for specific purposes. This research was published this month in Cell (here and here).

The scope of these papers is limited to microbiome data; no clinical endpoints are assessed. Without clinical evidence, it is not possible to conclude about the tested probiotic’s usefulness, and it is certainly not possible to conclude about probiotic usefulness in general. Stating that probiotics are ‘quite useless’ or ‘not as beneficial’ is, quite simply, wild and factually inaccurate. The authors discount the existing body of evidence for probiotic health benefits, including Level 1 placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Cochrane reviews (the gold standard used by physicians and public health policy makers) of the totality of evidence show that specific probiotics can prevent antibiotic associated diarrhea (AAD) and C. difficile diarrhea. This evidence has been translated into evidence-based recommendations for probiotics issued by medical groups. Regardless of an effect on the microbiota, these are established, evidence-based benefits of probiotics.

No clinical endpoints tracked in either study

What these papers provide is extensive data about the impact of one product containing 11 common probiotic species on different microbiome measures. To the authors’ credit, they analyzed mucosal and luminal samples from humans, in addition to samples from stool. Nonetheless, the probiotic definition [live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confers a health benefit on the host (Hill et al 2014)] does not require that probiotics function via interaction with the microbiota, nor is there much evidence that they alter the microbiota composition in an appreciable manner. Absence of impact on microbiome measures is not evidence that probiotics lack clinical or physiological effects. Probiotics function via many mechanisms that might not be revealed by the measures made in these papers.

Methodological concerns

A careful reading of this paper reveals many methodological concerns.

The extensive data in the paper is an assortment of different types of analyses. For example, for a beta-diversity metric, they sometimes use weighted Unifrac, sometimes unweighted Unifrac, and sometimes Bray-Curtis, without an explanation for their choice. These approaches to presenting the data can give very different results. With the transcriptomics data, sometimes the authors choose samples from the duodenum and sometimes the jejunum. For example, in figure 6, panels C-E compare the difference in gene expression between the naïve group and the treatment in the duodenum, whereas in panels F-H they compare the antibiotic state with the treatment in the jejunum. Such an approach leads the reader to speculate that the authors picked the metrics and data that best fitted the story they wanted to tell. In a well-conducted clinical trial, the statistical plan is registered before the study starts, to assure readers that the scientific process of advancing a hypothesis and designing a study to test the hypothesis is respected.

The probiotic was not administered to human subjects until 7 days after the treatment with antibiotics commenced, after the damage by the antibiotics has been done. Dozens of human studies with specific probiotics have documented that probiotics prevent AAD or C. difficile infection. In most clinical trials, the probiotic is administered together with the antibiotics. A recent meta-analysis concluded that “administration of probiotics closer to the first dose of antibiotic reduces the risk of (Clostridium difficile infection) by >50% in hospitalized adults.” (Emphasis added) The approach in the Suez et al paper is not consistent with the aforementioned clinical studies, with how probiotics are used in clinical practice or with the knowledge of how probiotics most likely prevent AAD. When provided on the same days as antibiotics, probiotics have the opportunity to prevent overgrowth of opportunistic, antibiotic-resistant microbes by competitive exclusion in the ecosystem. Therefore, the microbiome findings of Suez et al likely cannot be applied to clinical trials with such different time course of antibiotic/probiotic administration.

Several conclusions about the effect of probiotics on the microbiota were based on relative abundance measures, which do not relate to actual bacterial numbers or metabolic activity of all relevant species in the gut.

The antibiotic treatment used was potent for a study population that would otherwise not need antibiotics. Volunteers were administered oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg bi-daily and oral metronidazole 500 mg tri-daily for a period of 7 days. They are both very strong and indiscriminate antibiotics, having a severe impact on the gut microbiota. One could question if this drug therapy might have a different impact on the microbiome of a healthy person compared to a patient likely to receive this treatment, i.e., one whose microbiota ecosystem is disrupted by disease or fever.

The probiotic product

A serious issue is that the authors chose a product for this study that has no demonstrated clinical benefits. At a minimum, the product used for this study should have evidence for impact on antibiotic associated conditions, including symptoms or emergence of opportunistic pathogens. The 3 (possibly 2, as the latter 2 appear to be the publication of the same data) human studies conducted on this product (here, here and here), showed no clinical benefit. Thus, the investigators tested the potential benefits of a product for which no benefits had been previously shown. Further, the papers do not adequately describe the product; only a total count (25 billion) is given; counts of each strain – through the end of the administration period – should have been provided. Furthermore, the authors state about the product that “B. longum was probably represented by two strains.” This constitutes imprecise characterization unacceptable in a well-defined probiotic product.

Appearance of author bias

The conclusions reached in the papers promote a personalized approach to probiotic use. In an article on the BBC, the lead author stated, “In the future probiotics will need to be tailored to the needs of individual patients. And in that sense just buying probiotics at the supermarket without any tailoring, without any adjustment to the host, at least in part of the population, is quite useless.” The authors did not disclose they are involved with a company promoting this personalized approach.

Probiotic colonization

The authors suggest that their finding that probiotics do not colonize long term is noteworthy. In fact, researchers in this field have known this for 30 years: most probiotics do not colonize or become established as part of the resident microbiota. A 2016 paper by Madonado-Gomez et al was notable precisely because a Bifidobacterium longum strain was found that did persist. In most cases, probiotic effects are likely mediated by transient effects.

Responders and non-responders

A well-established concept in medicine is that some people respond clinically and physiologically to interventions and others don’t. This is the case with much of probiotic as well as pharmaceutical literature. (See review on responders and non-responders to probiotics by Reid et al.) An individual’s response is likely impacted by diet, resident microbes, host genes and host physiology/health. The validity of a personalized approach to probiotic administration remains to be determined, as evidence for a clinical benefit to the approach is needed. Microbiome data alone are not sufficient.

Need for future research

In the Cell publications, the authors acknowledge their study was limited due to lack of clinical endpoints and the testing of only a single product. It is unfortunate that the press marched ahead with inflammatory stories about the negative effects of probiotics based on such paltry evidence. The scientific community understands that this is one study, on a small number of human subjects, by one research group. Sweeping conclusions cannot be made. There are many hypotheses that can be generated from this study that can lead to follow up studies, which we hope will ensue.

Conclusions

Hundreds of human trials have demonstrated clinical benefits of probiotics and several evidence-based recommendations have been issued by medical organizations. Of course, not all studies are positive. Not all probiotics work for all conditions. But the safety record of probiotics administered to healthy as well as many patient populations is well-established. Numerous media outlets have reported on these two studies as if they are proof that probiotics are useless at best and harmful at worst. This irresponsible reporting may lead people who are benefitting from probiotics to stop using them, potentially causing real harm.

The erroneous interpretation of the current study and previous research by the primary author is disingenuous, as he states, “Contrary to the current dogma that probiotics are harmless and benefit everyone, these results reveal a new potential adverse side effect of probiotic use with antibiotics that might even bring long-term consequences.” This comment and the papers’ conclusions are not corroborated by the totality of safety and efficacy clinical evidence on probiotics, which includes thousands of probiotic-treated subjects. In comparison, the data in Suez et al come from microbiome assessments from only eight probiotic-treated subjects.

Furthermore, this paper evaluated just one product of limited provenance and containing a combination of multiple, incompletely characterized strains. This is in sharp contrast to numerous studies of precisely characterized strains demonstrating well-defined and beneficial engagements with the host. Zmora and colleagues and Suez and colleagues are to be congratulated on their attempts to characterize in detail the impact of one probiotic product on a perturbed, human microbiome. We look forward to further such studies employing well-characterized strains with demonstrated clinical benefits and including relevant clinical endpoints.

Additional reading:

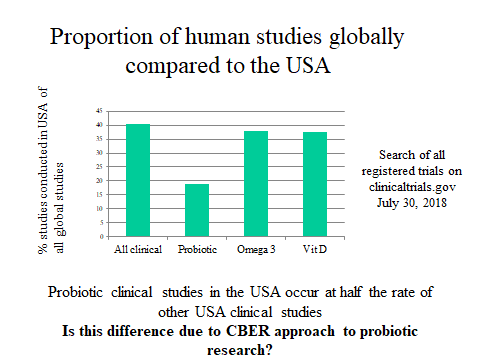

Risk assessment of probiotics use requires clinical parameters

ISAPP comments: International Group of Probiotic Scientists Weighs in on Flawed Conclusions From New Scientific Papers

American Gastroenterological Association response: AGA’s Interpretation of the Latest Probiotics Research

Response by Prof. Gregor Reid: Trying to Close the Stable Door After the Horse Has Bolted

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina

Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina