Decoding a Probiotic Product Label

By Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD

Interested in knowing what’s in your probiotic product? Unfortunately, there are many ways that probiotic product labels can fall short.

First, not all items labeled as “probiotic” truly meet the scientific criteria for a probiotic product. See here for information on what qualifies as a probiotic. Some fermented foods are marketed today claiming to be ‘probiotic’. But these products often have undefined microbial content and lack any studies documenting health effects, criteria that are required for a probiotic. Instead, such products could legitimately be labeled as containing ‘live, active cultures’. Dietary supplement products formulated with untested microbes should similarly not be labeled as probiotics.

Also, a label might not provide adequate information on what types of microbes are contained in the product. Genus and species may be listed, but no strain designation. Maybe only “bifidobacteria” or “lactobacilli” are listed.

They might not disclose the potency of individual strains in the product. Some may provide a total count of colony forming units (cfu)/dose or serving, which in the case of a single strain product is informative. But in the case of a multi-strain product – products may contain a couple or up to 30 strains – you don’t know if equal amounts of all strains are included, or perhaps the bulk of the count is made up of the strain in the formulation that is least expensive to manufacture rather than the one that will make the probiotic more effective. Some products may provide one count for “Lactobacillus” and another count for “Bifidobacterium”, a slightly more informative approach than just total count, but still lacking in detail. Many challenges exist for multi-strain products, including the lack of robust methods to quantify different strains once combined, especially viable ones. This topic was one that was covered in an ISAPP webinar, Current issues in probiotic quality: An update for industry.

The label may state that the count is “at time of manufacture”, a number that is no doubt inadequate if you purchase the product close to the end of its shelf-life. Most probiotic strains suffer cell count decline over the course of shelf-life, with some strains more susceptible than others. This situation almost guarantees that by the pull-by date for a multi-strain product, the ratio of cfu of strains to each other is likely much different than at the time of formulation.

Surveys of probiotic product labels

Additionally, it is difficult for consumers to know what products are backed by studies documenting a health benefit. If a product is not labeled sufficiently, it is impossible to link it to evidence. Two studies surveyed commercial probiotic products in the Washington DC area, Retail Refrigerated Probiotic Foods and Their Association with Evidence of Health Benefits and More Information Needed on Probiotic Supplement Product Labels. Results showed that 45% of retail dietary supplement products did not provide strain designations and an equal number did not provide a measure of potency through the end of shelf-life. Only 35% of products could be linked (based on strain and dose) to evidence of a health benefit. Food products fared a bit better, with 49% of refrigerated probiotic food products being linked to evidence of a health benefit. One clear indication from this study was that if your food product discloses the strain designation, it is likely to have evidence of a health benefit. An overall conclusion was that product labeling – at least in this region – needs improvement.

Historical context on guidelines for probiotic product labels

According to the FAO/WHO 2002 Working Group on Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food (page 39 of this combined document), the following information should be on probiotic labels:

– Genus, species and strain designation for each probiotic strain in the product.

– Minimum viable numbers of each probiotic strain at the end of the shelf-life, typically expressed in colony forming units (or cfu).

– The suggested serving size (or dose) must deliver the effective dose of probiotics related to any health benefit communicated on the label.

– Health claim(s) (as allowed by law and substantiated by studies)

– Proper storage conditions

– Corporate contact details for consumer information

These principles are developed and reiterated in “Best Practices Guidelines for Probiotics” (2017) developed by the Council for Responsible Nutrition and IPA.

Additional information

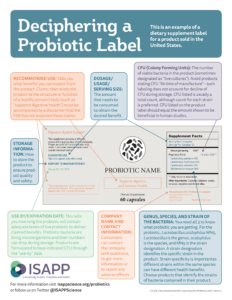

ISAPP created an infographic to explain the information on a probiotic labels. Our example portrays an imaginary dietary supplement for sale in the United States. Labels on foods containing a probiotic or a probiotic produced in another country would be labeled differently from this example to comply with applicable regulations. For those interested in probiotic labels in the EU, see the infographic ISAPP created for a probiotic product in the European Union. Also of interest, USP.org created an infographic on “How to Read a Dietary Supplement Label” for U.S. products.