1-6 of 6 results

-

What is a strain in microbiology and why does it matter?

By Prof. Colin Hill, Microbiology Department and APC Microbiome Ireland, University College Cork, Ireland At the recent ISAPP meeting in… -

Behind the publication: Understanding ISAPP’s new scientific consensus definition of postbiotics

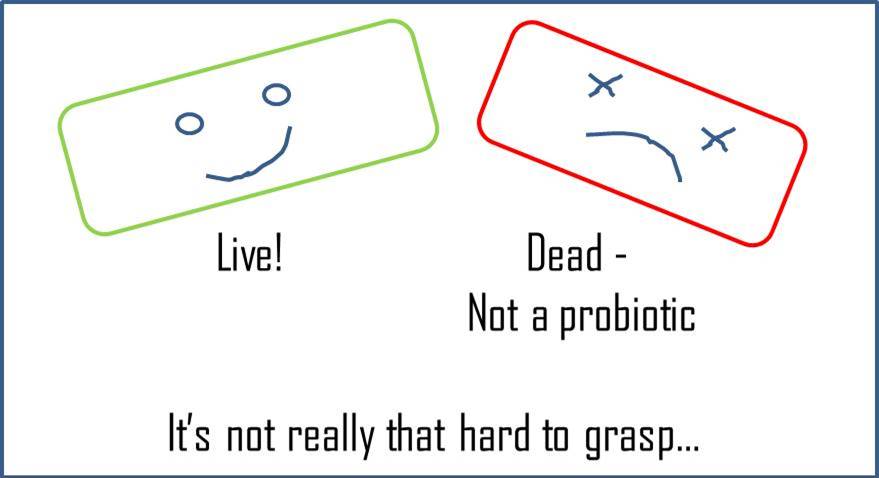

A key characteristic of a probiotic is that it remains alive at the time of consumption. Yet scientists have known… -

How do probiotics stay alive until they are consumed?

Open a food supplement containing probiotics and you will probably find a white dry powder. This is what the microbes may look like in their dormant state, due to a technological process called freeze-drying or lyophilization. -

The Children of Masiphumelele Township

Gregor Reid PhD MBA FCAHS FRSC, Professor, Western University and Scientist, Lawson Health Research Institute, London, Canada Just off the… -

Dead bacteria – despite potential for benefit – are not probiotics

Re-posted from an original blog article by Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP Executive Science Officer At the 2018 International Scientific… -

Microbiome Analysis – Hype or Helpful?

By Karen Scott, PhD, Rowett Institute, University of Aberdeen, Scotland Since we have realized that we carry around more microbial…