A key characteristic of a probiotic is that it remains alive at the time of consumption. Yet scientists have known for decades that some non-living microorganisms can also have benefits for health: various studies (reviewed in Ouwehand & Salminen, 1998) have compared the health effects of viable and non-viable bacteria, and some recent investigations have tested the health benefits of pasteurized bacteria (Depommier et al., 2019).

Since non-viable microorganisms are often more stable and convenient to include in consumer products, interest in these ‘postbiotic’ ingredients has increased over the past several years. But before now, the scientific community had not yet united around a definition, nor had it precisely delineated what falls into this category.

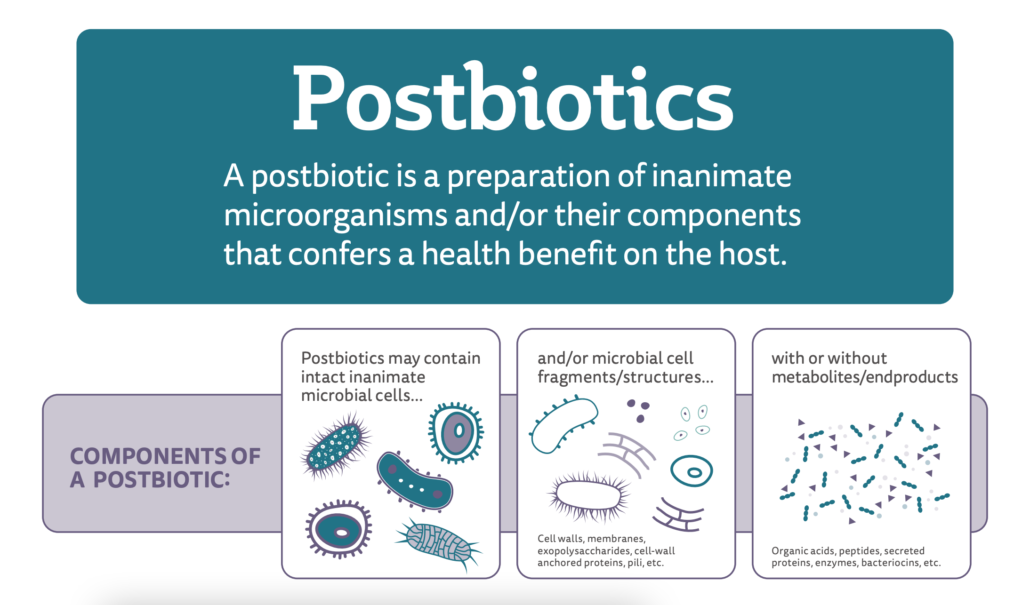

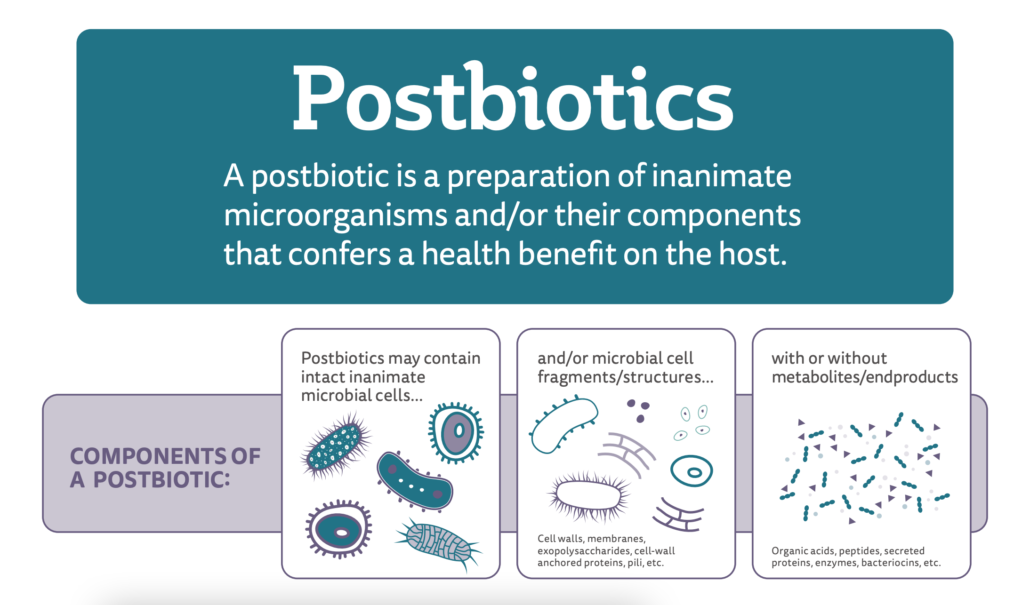

An international group of scientists from the disciplines of probiotics and postbiotics, food technology, adult and pediatric gastroenterology, pediatrics, metabolomics, regulatory affairs, microbiology, functional genomics, cellular physiology and immunology met in 2019 to discuss the concept of postbiotics. This meeting led to a recently published consensus paper, including this definition: “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host”.

Thus, a postbiotic must include some non-living microbial biomass, whether it be whole microbial cells or cell components.

Below is a Q&A with four of the paper’s seven ISAPP-linked authors, who highlight important points about the definition and explain how it will lay the groundwork for better scientific understanding of non-viable microbes and health in the years ahead.

Why was the concept of postbiotics needed?

Prof. Seppo Salminen, University of Turku, Finland:

We have known for a long time that inactivated microorganisms, not just live ones, may have health effects but the field had not coalesced around a term to use to describe such products or the key criteria applicable to them. So we felt we needed to assemble key experts in the field and provide clear definitions and criteria.

Further, novel microbes (that is, new species hitherto not used in foods) in foods and feeds are being introduced as live or dead preparations. The paper highlights regulatory challenges and for safety and health effect assessment for dead preparations of microbes.

Can bacterial metabolites be postbiotics?

Prof. Gabriel Vinderola, National University of Litoral, Argentina:

Postbiotics can include metabolites – for example, fermented products with metabolites and microbial cells or their components, but pure metabolites are not postbiotics.

Can you expand on what is not included in the category of postbiotics?

Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP Executive Science Officer, USA:

The term ‘postbiotic’ today is sometimes applied to components derived from microbial growth that are purified, so no cell or cell products remain. The panel made the decision that such purified, microbe-derived substances (e.g. butyrate) should be called by their chemical names and that there was no need for a single encompassing term for them. Some people may be surprised by this. But microbe-derived substances include a whole host of purified pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals, and these are not appropriately within the scope of ‘postbiotics’.

For something to be a postbiotic, what kinds of microorganisms can it originate from?

Prof. Gabriel Vinderola, National University of Litoral, Argentina:

A postbiotic must derive from a living microorganism on which a technological process is applied for life termination (heat, high pressure, oxygen exposure for strict anaerobes, etc). Viruses, including bacteriophages, are not considered living microorganisms, so postbiotics cannot be derived from them.

Safety and benefits must be demonstrated for its non-viable form. A postbiotic does not have to be derived from a probiotic (see here for a list of criteria required for a probiotic). So the microbe used to derive a postbiotic does not need to demonstrate a health benefit while alive. Further, a probiotic product that loses cell viability during storage does not automatically qualify as a postbiotic; studies on the health benefit of the inactivated probiotic are still required.

Vaccines or substantially purified components and products (for example, proteins, peptides, exopolysaccharides, SCFAs, filtrates without cell components and chemically synthesized compounds) would not qualify as postbiotics in their own right, although some might be present in postbiotic preparations.

What was the most challenging part of creating this definition?

Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP Executive Science Officer, USA:

The panel didn’t want to use the term ‘inactive’ to describe a postbiotic, because clearly even though they are dead, they retain biological activity. There was a lot of discussion about the word ‘inanimate’, as it’s not so easy to translate. But the panel eventually decided it was the best option.

Does this definition encompass all postbiotic products, no matter whether they are taken as dietary supplements or drugs?

Prof. Hania Szajewska, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland:

Indeed. However, as of today, postbiotics are found primarily in foods and dietary supplements.

Where can you currently find postbiotics in consumer products, and what are their health effects?

Prof. Hania Szajewska, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland:

One example is specific fermented infant formulas with postbiotics which have been commercially available in some countries such as Japan and in Europe, South America, and the Middle East for years. The postbiotics in fermented formulas are generally derived from fermentation of a milk matrix by Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, and/or Lactobacillus strains.

Potential clinical effects of postbiotics include prevention of common infectious diseases such as upper respiratory tract infections and acute gastroenteritis. Moreover, fermented formulas have the potential to improve some digestive symptoms or discomfort (e.g. colic in infants). In addition, there is some rationale for immunomodulating, anti-inflammatory effects which may potentially translate into other clinical benefits, such as improving allergy symptoms. Still, while these effects are likely, more well-designed, carefully conducted trials are needed.

What do we know about postbiotic safety?

Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP Executive Science Officer, USA:

Living microbes have the potential, especially in people with compromised health, to cause an infection. But because the microbes in postbiotics are not alive, they cannot cause infections. This risk factor, then, is removed from these preparations. Of course, the safety of postbiotics for their intended use must be demonstrated, but infectivity should not be a concern.

What are the take-home points about the postbiotics definition?

Prof. Seppo Salminen, University of Turku, Finland:

Postbiotics, which encompass inanimate microbes with or without metabolites, can be characterized, are likely to be more stable than live counterparts and are less likely to be a safety concern, since dead bacteria and yeast are not infective.

Read the postbiotic definition paper here.

See the press release about this paper here.

View an infographic on the postbiotic definition here.

See another ISAPP publication on postbiotics here.