How to respond to the question “Should I take a probiotic?”

By Dr. Mary Ellen Sanders PhD and Prof. Daniel Merenstein MD

A Washington Post article published March 11, 2025 by a gastroenterologist addressed a question posed by a reader: “I’ve heard about the benefits of probiotics for years. Should I start taking them?”

We both get this question frequently, and over the years have answered it differently than this journalist. Here’s what we would say.

We would first ask if there are symptoms that are motivating the question. If yes, then we would look to see if any probiotics have been studied to address the issue. Places to check for any evidence include the World Gastroenterological Organisation Guidelines and the Clinical Guide to Probiotic Products* Available in USA, Canada or UK. A 2018 review article addressed the question of how physicians might choose a probiotic for their patients. These resources are compiled after review of evidence by physicians and scientists.**

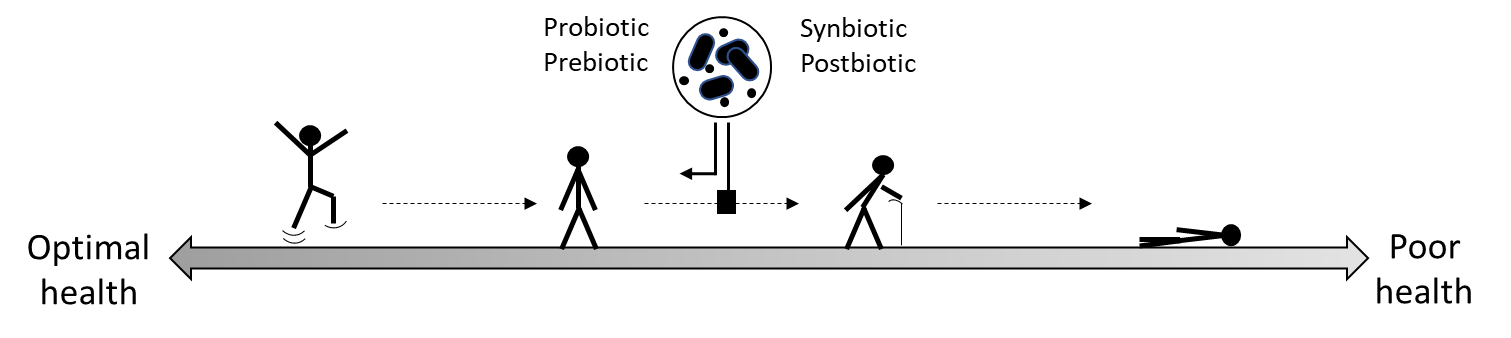

These resources show that there are many randomized controlled trials of probiotics for a variety of conditions. These studies have found that probiotic strains can impact health or mitigate some conditions, including reducing crying time in colicky babies, improving some mental health endpoints such as anxiety and depressive symptoms, and reducing diarrhea from antibiotics So, if these endpoints are of interest, there may be a probiotic to try.

If no symptoms are being targeted, we would explain that there is not highest level evidence – i.e., systematic review of (homogeneous) randomized controlled trials or individual randomized controlled trials (Level A evidence) – that probiotics are beneficial for generally healthy people (Merenstein et al 2024). But context is needed here: there is not Level A evidence for almost any interventions for healthy people, with the exception of some, not most, cancer screening tests, and some, not all, vaccines. Even with diet and exercise it is difficult to find Level A evidence for healthy people.

We would stress that not all probiotics are the same, and it’s important to choose a specific probiotic to match your goals. Because traditional probiotic strains have a very good safety record, the major downside to trying one is economic. It’s reasonable to try a probiotic for 30 days and if it does help, great. If it doesn’t help, quit. This can be especially useful for GI conditions without good options, such as IBS, which is multifactorial and difficult to treat; also, available medicines are expensive, and have a limited scope. Remember that different people will respond differently to a probiotic (this is also true for drugs).

We would provide advice on how to navigate the probiotic marketplace.

- Purchase from reputable companies. There is no regulatory pre-market approval of claims or content on dietary supplements or foods in most jurisdictions. Good companies substantiate their claims.

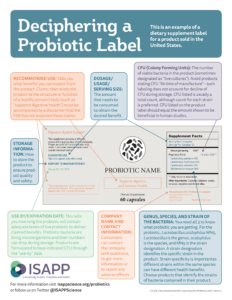

- Purchase only dietary supplement products that state the strain designations and counts through end of shelf life. Learn how to read a probiotic dietary supplement label in this infographic by ISAPP.

- Refrigerated food sources of probiotics – such as many yogurts – should also be labeled with strain designations and count, but these products are typically short shelf-life products, so they usually don’t state count at the end of shelf life.

We might share that we undertook a survey of both probiotic dietary supplements and refrigerated probiotic foods at the retail level and found that about 35% of the supplements and 49% of the foods could be traced to published evidence. In general, products listing strain designations also had evidence for some health benefit.

We would warn about wild claims made on the internet and in social media – for any product. Be skeptical.

We would say that contrary to popular belief, even among GI docs, the evidence that fiber and live dietary microbes (such as in some fermented foods) can improve your gut microbiome is limited. In spite of all the research to date, scientists cannot define a healthy microbiome composition, so how can we know how to improve it? However, we know that fiber improves some parameters of gut health and reduces risk of some chronic diseases, but most of us do not eat the recommended daily allowance of fiber. So, increasing dietary fiber from fruits, vegetables and whole grains is a sound recommendation.

But for traditional fermented foods such as kimchi, kombucha and kefir, few randomized controlled trials have documented meaningful health benefits. Some interesting associations have been discovered between increasing live microbes in the diet and health biomarkers (Hill et al. 2024), but these observations need to be confirmed in controlled trials. Still, traditional fermented foods can be nutritious additions to your diet even though most lack convincing evidence about their health benefits beyond nutrition. This fact is often overlooked by many ‘experts’, who, without evidence, recommend consumption of traditional fermented foods to improve gut health while criticizing limitations in probiotic research.

Finally, we would not criticize probiotics because the industry is profitable (if that were the benchmark, where does that leave the pharmaceutical industry?), because probiotic studies are heterogeneous (studies on many categories, including fiber, are as well), because they are not ‘personalized’ (precious few intervention in nutrition OR medicine are personalized – see here) or because many YouTube videos on probiotics are not scientifically accurate (we think it’s safe to say this is not a problem unique to probiotics. For reliable videos on probiotics, see here).

* If using the Clinical Guides, it is best to focus on products with Level I evidence, defined as “Evidence obtained from at least one appropriately designed trial, (e.g., randomization, blinding, appropriate population comparisons)”. Level II or III evidence is worth reviewing but is not high-level evidence.

**As the Washington Post article referenced above indicated, the American Gastroenterological Association thoroughly reviewed evidence for probiotics for a range of GI disorders. They conditionally recommended certain probiotics for prevention of C. difficile and prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. They did not review information on a well-studied probiotic GI endpoint, antibiotic-associated diarrhea (Cochrane reviews recommend probiotics for adults and children taking antibiotics), nor on any non-GI endpoints.