By Dr. Gabriel Vinderola, PhD, Associate Professor of Microbiology at the Faculty of Chemical Engineering from the National University of Litoral and Principal Researcher from CONICET at Dairy Products Institute (CONICET-UNL), Santa Fe, Argentina

The recently published ISAPP consensus paper defines a postbiotic as “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host“. Such a definition quickly brings to mind that a postbiotic is not equivalent to microbial metabolites. A postbiotic should also contain inanimate microbial cells or cell fragments. Metabolites or fermentation products may be present, but they are not required.

Because microbes are complex entities, we must be open to innovative understandings of what a postbiotic might entail. Indeed, although not explicitly mentioned in the ISAPP consensus paper, extracellular membrane vesicles may comprise an innovative conceptualization of a postbiotic, falling within the ‘cell component’ part of the postbiotic definition.

Bacterial vesicles

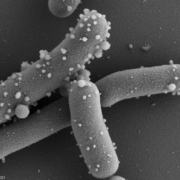

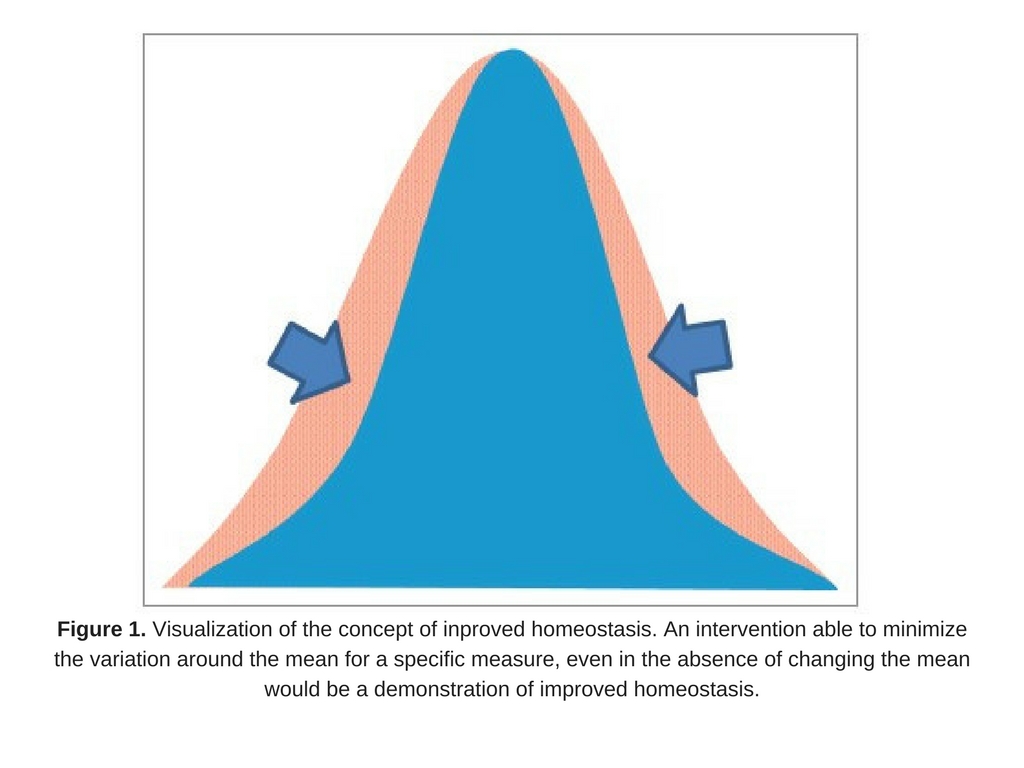

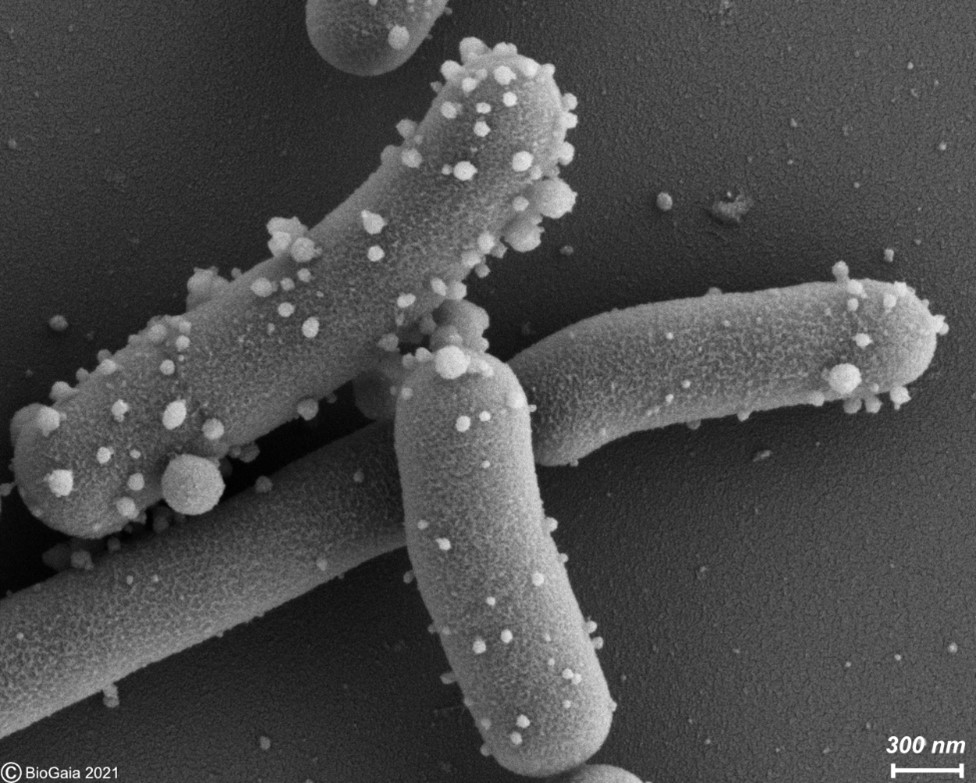

Extracellular membrane vesicles (EMV) are universal carriers of biological information produced in all domains of life. Bacterial EMV are small, spheroidal, membrane-derived proteoliposomal nanostructures, typically ranging from 25 – 250 nm in diameter, containing proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, metabolites, numerous surface molecules and many other biomolecules derived from their progenitor bacteria (Figure 1). Bacterial vesicles have been known for more than 50 years as structures able to carry cellular material (Ñahui Palomino et al. 2021). However, studies on membrane vesicles derived from Gram-positive bacteria are more recent as it was for a time believed they were incapable of producing vesicles due to their thick and complex cell walls, and the lack of an outer membrane. Today, EMVs have been isolated from Gram-positive probiotic bacteria, including those belonging to the Lactobacillaceae family (under which Lactobacillus was recently split into many new genera) and the Bifidobacterium genus. In probiotic bacteria, vesicles may mediate quorum sensing and material exchange. Perhaps even more important, they can act as mediators of bacteria-to-cell and bacteria-to-bacteria interactions. As bacterial EMV are inanimate structures that cannot replicate, they fit the postbiotic definiton as cell components as long as other criteria stipulated by the definition are met.

Figure 1. Membrane vesicles budding on the surface of L. reuteri DSM 17938 and released into the surrounding medium. These vesicles were described in by Grande et al. 2017. Photo used with permission of BioGaia.

Functions of bacterial vesicles related to potential health benefits

Underlying mechanisms and corresponding molecules driving health effects of bacterial vesicles are not well understood, in part due to reliance on in vitro models. Bacterial EMV derived from Lactobacillaceae spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia spp. have been reported to alleviate metabolic syndrome and allergy symptoms, promote T-cell activation and IgA production, strengthen gut barrier function, and exhibit anti-viral and immunomodulatory properties (Kim et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2018; Ashrafian et al. 2019; Molina-Tijeras et al. 2019; Palomino et al. 2019; Shehata et al. 2019; Bäuerl et al. 2020). Interestingly, vesicles from Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 (West et al. 2020) and Lacticaseibacillus casei BL23 (Domínguez Rubio et al. 2017) may accomplish some of the the effects of these probiotic bacteria. In fact it is not unreasonable to think that EMVs may be already present and active in probiotic products.

Challenges for bacterial vesicle production

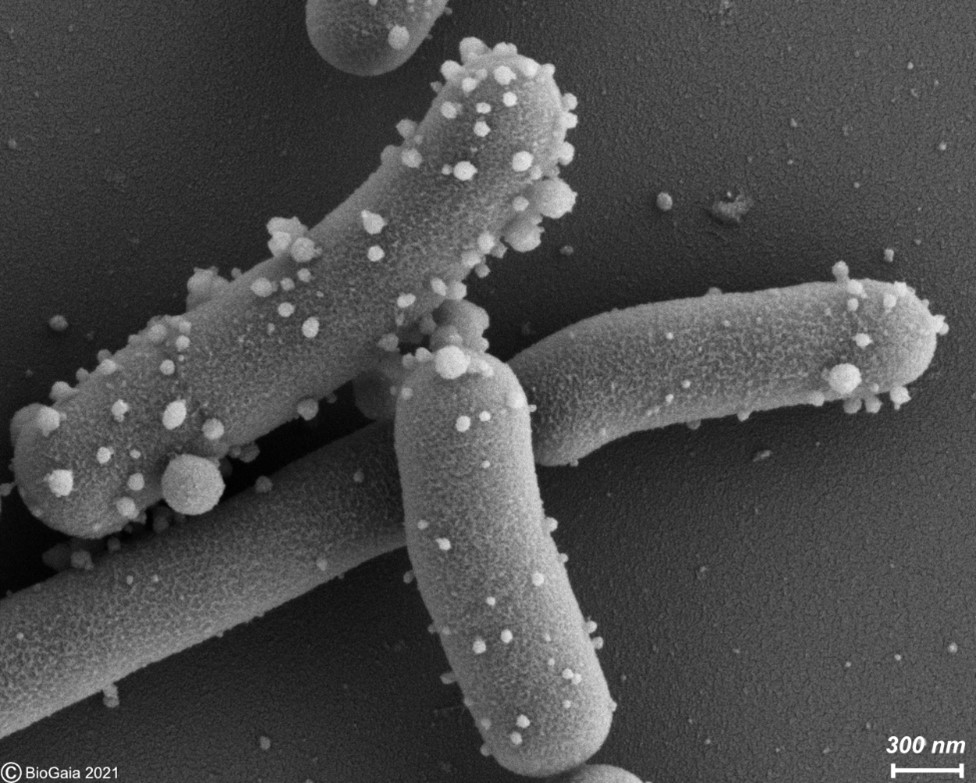

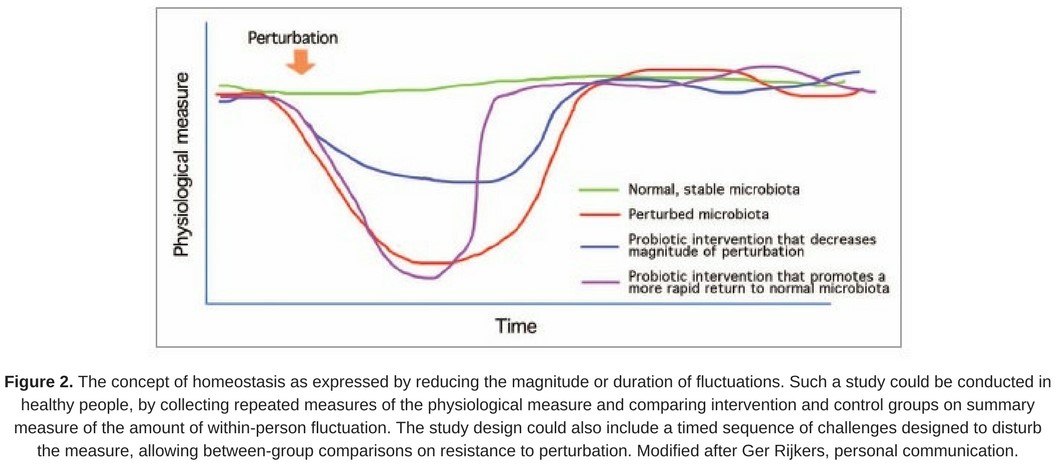

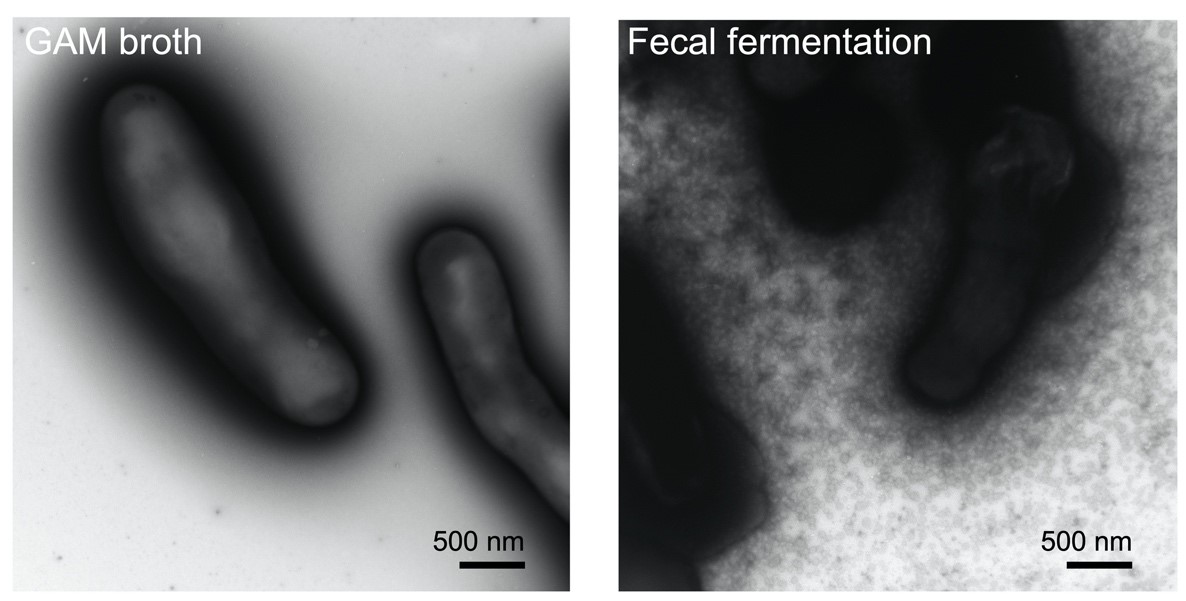

To develop a postbiotic from microbial EMVs, many challenges need to be overcome. Defining optimal cultivation conditions, and methods for vesicle release, isolation and scaling up are some of the challenges of bacterial vesicle production. There are several studies showing that altering the cultivation parameters can impact vesicle production. Examples of treatments shown to increase vesicle release include exposure to UV radiation and antibiotic pressure (Gamalier et al. 2017; Gill et al. 2019). Exposure to glycine has also been shown to increase vesicle production (Hirayama & Nakao 2020). Interventions during culture, for example by introducing agitation and varying pH, can possibly be ways to potentiate vesicle release and increase their bioactivity (Müller et al. 2021). A recent report also revealed that B. longum NCC2705 released a myriad of vesicles when cultured in human fecal fermentation broth, but not in basal GAM anaerobic medium (Figure 1). Moreover, the B. longum vesicle production pattern differed among individual fecal samples suggesting that metabolites derived from symbiotic microbiota stimulate the active production of vesicles in a different manner (Nishiyama et al. 2020). Whether any of these treatments and culture conditions are general or strain specific remains to be elucidated. Large differences in the number of vesicles that may be obtained by different extraction methods can occur (Tian et al. 2020). Tangential flow filtration or the use of antibodies targeting specific epitopes of the vesicles are some of the options proposed for the large scale isolation of EMV (Klimentová & Stulík 2015).

Figure 2. Left: Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705 grown on GAM broth. Right: secretion of membrane vesicles by Bifidobacterium longum NCC2705: the strain was cultured in bacterial-free human fecal fermentation broth and secreted a myriad of membrane vesicles. Reported and adapted from Nishiyama et al. 2020.

Progress has been made on the production of bacterial vesicles in recent years, yet several issues remain to be clarified including how vesicles are generated from the progenitor microbe, how the composition of vesicles changes according to the culture conditions, how to target specific bacterial vesicle purification from a pool of vesicles derived from other organisms (for example, bacterial vesicles produced in milky media can be accompanied by vesicles from eukaryotic cells present in the milk), safety aspects, quantification methods and the regulation of their use by the corresponding authority.

Their future as potential postbiotics

Membrane vesicles are an exciting opportunity for the development of postbiotics. A potential benefit of vesicles is that their small size compared to whole cells may enable them to more readily migrate to host tissues that could not be otherwise reached by a whole cell (Kulp & Kuehn 2010). Their nanostructure enables them to penetrate through the gut barrier and to be delivered to previously unreachable sites through the bloodstream or lymphatic vessels, and to interact with different cell types (Jones et al. 2020). For example, bacterial rRNA and rDNA found in the bloodstream and the brain of Alzheimer’s patients were postulated to have originated from bacteria vesicles (Park et al. 2017). Safety of EMVs must be carefully considered and assessed, even if they are derived from microbes generally recognized as safe, as their small size may increase penetration capacity with potential and yet unknown systemic effects. Novel postbiotics derived from microbial membrane vesicles is an intriguing area for future research to better understand production parameters, safety and functionality.

Thanks to Cheng Chung Yong, postdoctoral researcher at Morinaga Milk Industry Co., LTD (Japan) and Ludwig Lundqvist, industrial PhD student at BioGaia AB (Sweden) for their contributions to this blog, and Mary Ellen Sanders and Sarah Lebeer from ISAPP for fruitful discussions.

References

Ashrafian, F., Shahriary, A., Behrouzi, A., Moradi, H.R., Keshavarz Azizi Raftar, S., Lari, A., Hadifar, S., Yaghoubfar, R., Ahmadi Badi, S., Khatami, S. and Vaziri, F., 2019. Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles as a mucosal delivery vector for amelioration of obesity in mice. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, p.2155.

Bäuerl, C., Coll-Marqués, J.M., Tarazona-González, C. and Pérez-Martínez, G., 2020. Lactobacillus casei extracellular vesicles stimulate EGFR pathway likely due to the presence of proteins P40 and P75 bound to their surface. Scientific reports, 10(1), pp.1-12.

Domínguez Rubio, A.P., Martínez, J.H., Martínez Casillas, D.C., Coluccio Leskow, F., Piuri, M. and Pérez, O.E., 2017. Lactobacillus casei BL23 produces microvesicles carrying proteins that have been associated with its probiotic effect. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, p.1783.

Gamalier, J.P., Silva, T.P., Zarantonello, V., Dias, F.F. and Melo, R.C., 2017. Increased production of outer membrane vesicles by cultured freshwater bacteria in response to ultraviolet radiation. Microbiological research, 194, pp.38-46.

Grande, R., Celia, C., Mincione, G., Stringaro, A., Di Marzio, L., Colone, M., Di Marcantonio, M.C., Savino, L., Puca, V., Santoliquido, R. and Locatelli, M., 2017. Detection and physicochemical characterization of membrane vesicles (MVs) of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, p.1040.

Gill, S., Catchpole, R. & Forterre, P., 2019. Extracellular membrane vesicles in the three domains of life and beyond. FEMS microbiology reviews, 43(3), pp.273–303.

Hirayama, S. & Nakao, R., 2020. Glycine significantly enhances bacterial membrane vesicle production: a powerful approach for isolation of LPS-reduced membrane vesicles of probiotic Escherichia coli. Microbial biotechnology, 13(4), pp.1162–1178.

Jones, E.J., Booth, C., Fonseca, S., Parker, A., Cross, K., Miquel-Clopés, A., Hautefort, I., Mayer, U., Wileman, T., Stentz, R. and Carding, S.R., 2020. The uptake, trafficking, and biodistribution of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron generated outer membrane vesicles. Frontiers in microbiology, 11, p.57.

Kim, J.H., Jeun, E.J., Hong, C.P., Kim, S.H., Jang, M.S., Lee, E.J., Moon, S.J., Yun, C.H., Im, S.H., Jeong, S.G. and Park, B.Y., 2016. Extracellular vesicle–derived protein from Bifidobacterium longum alleviates food allergy through mast cell suppression. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 137(2), pp.507-516.

Kulp, A. & Kuehn, M.J., 2010. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annual review of microbiology, 64, pp.163–184.

Molina-Tijeras, J.A., Gálvez, J. & Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E., 2019. The immunomodulatory properties of extracellular vesicles derived from probiotics: a novel approach for the management of gastrointestinal diseases. Nutrients, 11(5), p.1038.

Müller, L., Kuhn, T., Koch, M. and Fuhrmann, G., 2021. Stimulation of probiotic bacteria induces release of membrane vesicles with augmented anti-inflammatory activity. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 4(5), pp.3739-3748.

Ñahui Palomino, R.A., Vanpouille, C., Costantini, P.E. and Margolis, L., 2021. Microbiota–host communications: Bacterial extracellular vesicles as a common language. PLoS Pathogens, 17(5), p.e1009508.

Nishiyama, K., Takaki, T., Sugiyama, M., Fukuda, I., Aiso, M., Mukai, T., Odamaki, T., Xiao, J. Z., Osawa, R., & Okada, N. 2020. Extracellular vesicles produced by Bifidobacterium longum export mucin-binding proteins. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 86(19), e01464-20.

Palomino, R.A.Ñ., Vanpouille, C., Laghi, L., Parolin, C., Melikov, K., Backlund, P., Vitali, B. and Margolis, L., 2019. Extracellular vesicles from symbiotic vaginal lactobacilli inhibit HIV-1 infection of human tissues. Nature communications, 10(1), pp.1-14.

Park, J.Y., Choi, J., Lee, Y., Lee, J.E., Lee, E.H., Kwon, H.J., Yang, J., Jeong, B.R., Kim, Y.K. and Han, P.L., 2017. Metagenome analysis of bodily microbiota in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease using bacteria-derived membrane vesicles in blood. Experimental neurobiology, 26(6), p.369.

Shehata, M.M., Mostafa, A., Teubner, L., Mahmoud, S.H., Kandeil, A., Elshesheny, R., Boubak, T.A., Frantz, R., Pietra, L.L., Pleschka, S. and Osman, A., 2019. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles (omvs)-based dual vaccine for influenza a h1n1 virus and mers-cov. Vaccines, 7(2), p.46.

Tan, K., Li, R., Huang, X. and Liu, Q., 2018. Outer membrane vesicles: current status and future direction of these novel vaccine adjuvants. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, p.783.

Tian, Y., Gong, M., Hu, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, W., Zhang, M., Hu, X., Aubert, D., Zhu, S., Wu, L. and Yan, X., 2020. Quality and efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation methods by nano-flow cytometry. Journal of extracellular vesicles, 9(1), p.1697028.

West, C.L., Stanisz, A.M., Mao, Y.K., Champagne-Jorgensen, K., Bienenstock, J. and Kunze, W.A., 2020. Microvesicles from Lactobacillus reuteri (DSM-17938) completely reproduce modulation of gut motility by bacteria in mice. PloS one, 15(1