Forthcoming changes in Lactobacillus taxonomy

I was privileged to be included in a small meeting of scientists, both academic and industry, who met last week in Verona to discuss changes in Lactobacillus taxonomy. The first objectives of the meeting were to clarify with industry the need for the proposed changes and to clarify the methodology that will be used. The second objectives were to discuss at large potential consequences and approaches to address them.

Changes to the Lactobacillus genus

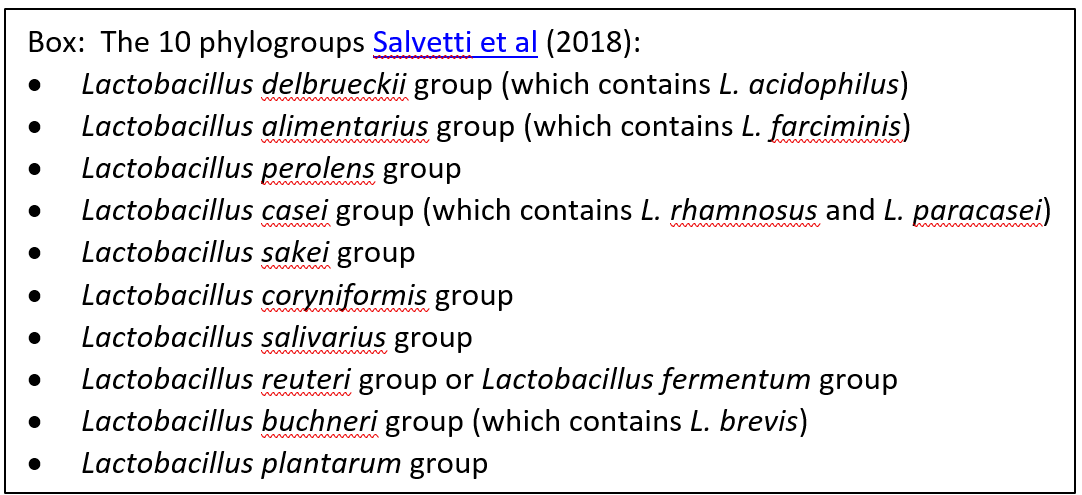

Experts from the Taxonomic Subcommittee for Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria and Related Organisms agreed that the genus Lactobacillus is too heterogeneous and dividing this genus into several genera is inevitable. The need for this taxonomic ‘correction’ has been known for a long time, but until recently, the methodologies needed to reliably group the current Lactobacillus species into new genera were not available. But earlier this year, a paper by Salvetti et al (2018) analyzed 269 Lactobacillus and related (e.g., Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, Fructobacillus, Oenococcus) species and showed that the Lactobacillus genus comprises 10 phylogroups (see box). Each of these phylogroups represents at least one new genus. These same 10 phylogroups were observed using three separate approaches [phylogenetic analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences, whole genome sequence analysis, leading to the comparison of 72 shared housekeeping genes (the core genome), and the comparison of average amino acid identity and percentage of conserved proteins], providing strong evidence that these groupings are robust. Commercially important Lactobacillus probiotic strains span at least 7 of those newly defined phylogroups; food fermentation lactobacilli cover even more.

Although these 10 phylogroups were identified by this study, the current genus Lactobacillus could ultimately be resolved into 10 or up to 23 genera, depending on the cut-off values used for the different approaches. If researchers choose to split the genus into fewer new genera, it increases the chance that taxonomic changes will be needed in the nearer future. If they split the genus into more genera, it increases the chance that nomenclature will remain stable.

The names of the new genera are not decided. New names must be published (or validated) in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. The authors of the publication will propose the new genus names. All species will be retained and their species names will not change. To minimize disruption, researchers will try to propose new genera names that begin with the letter “L”. Because “Lactobacillus” is a masculine Latin noun, the new genus names must be masculine for the species names to be retained.

A silver lining

Critics of these changes may suppose that adhering to taxonomic convention is their only purpose. But a classification system that better reflects genetic relatedness of the species may reap other benefits. As evidence for clinical benefits accumulates (summarized in open access review “Probiotics for Human Use”, 2018) and investigations provide insight into probiotic mechanisms of action, a clearer image of mechanisms and functions associated with particular taxonomic groups may emerge. The concept of core, shared benefits that were not strain-specific but linked to higher taxonomic groupings was explored in two ISAPP publications [Hill et al. (2014) and more in depth in Sanders et al. (2018)]. Reconsideration of clinical evidence and its relationship to new genera might prove enlightening.

What can be done to minimize confusion?

The meeting attendees brainstormed potential complications that might result from changing genus names. Company representatives in general considered that internal changes could be managed, although resources would be required to update names on all different paperwork and labels associated with commercial products (for example, marketing materials, product information, certificates of analysis, labeling, import/export certificates). The 2002 WHO/FAO probiotic guidelines, as well as the 2017 CRN/IPA guidelines, indicate that the genus, species and strain designation should be included on product labels. Further, the name used should reflect current nomenclature. This requirement is reflected in some national regulations. Therefore, genus name changes will necessitate label changes.

Further, it was emphasized that a clear document should be prepared and endorsed by reputable organizations (EFSA, NIH, FDA, medical organizations, and others). The document should: (a) indicate the name changes, (b) provide a clear, concise statement of why the changes were needed, and (c) emphasize that only the names, not the strains, would be different. This could be leveraged by companies to communicate with all stakeholders. End-users of probiotic products would likely not be a significant communication challenge. Authorities involved with probiotic safety (FDA with GRAS and EFSA with QPS) likely will manage these changes, as they are science-based. More of a concern was communication with other regulators, both at the level of national agencies responsible for probiotic-specific regulations (including countries with positive lists of species that are acceptable as probiotics) as well as authorities involved in import/export of product. Some potential issue with intellectual property may be envisaged, especially in a transition period during which the new names are not routinely used yet.

The bottom line: Name will change but the strains will stay the same

The current Lactobacillus genus will be split into at least 10, and perhaps as many as 23, genera. No species names will change, but many species – including commercially important ones – will have a different genus names, hopefully beginning with the letter “L”. Because of the tremendous heterogeneity of the current Lactobacillus genus, Prof. Paul O’Toole concluded his presentation saying “the status quo is not an option.” Some disruptions can be expected from this massive change, but the probiotic field would benefit from embracing these changes and developing strategies to minimize any difficulties resulting from them.

Additional information:

The International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes (ICSP) and the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria are responsible for the naming of bacteria. The subcommittee of the ICSP responsible for naming lactobacilli is the Taxonomic Subcommittee for Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria and Related Organisms.

The meeting was convened by the Lactic Acid Bacteria Industrial Platform and chaired by Esben Laulund of Chr Hansens, who also chairs IPA Europe. A full report of meeting conclusions is expected to be published in a scientific journal by the end of 2018. Abstracts and program will to be posted on the LABIP website in due time.

The taxonomic hierarchy for Lactobacillus currently is: Domain: Bacteria; Division/Phylum: Firmicutes; Class: Bacilli; Order Lactobacillales; Family: Lactobacillaceae; Genus: Lactobacillus. The lowest order of taxonomy is the subspecies; the strain designation has no official standing in nomenclature. There are currently over 230 recognized species of Lactobacillus, and approximately 10 new species are added each year.