Episode 28: Lactobacilli in the microbiomes of the gut, skin, reproductive tract and more

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

The Science, Microbes & Health Podcast

This podcast covers emerging topics and challenges in the science of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics and fermented foods. This is the podcast of The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), a nonprofit scientific organization dedicated to advancing the science of these fields.

Lactobacilli in the microbiomes of the gut, skin, reproductive tract and more, with Prof. Kingsley Anukam PhD

Episode summary:

In this episode, the ISAPP podcast hosts cover a range of topics related to lactobacilli and health with Prof. Kingsley Anukam PhD from Nnamdi Azikiwe University in Nigeria. Prof. Anukam has a special interest in lactobacilli, and studies lactobacilli in microbiomes across many different contexts: fermented foods, skin, gut, and reproductive tract sites. He talks about the wide range of research he has led in Nigeria using diverse sources of funding.

Key topics from this episode:

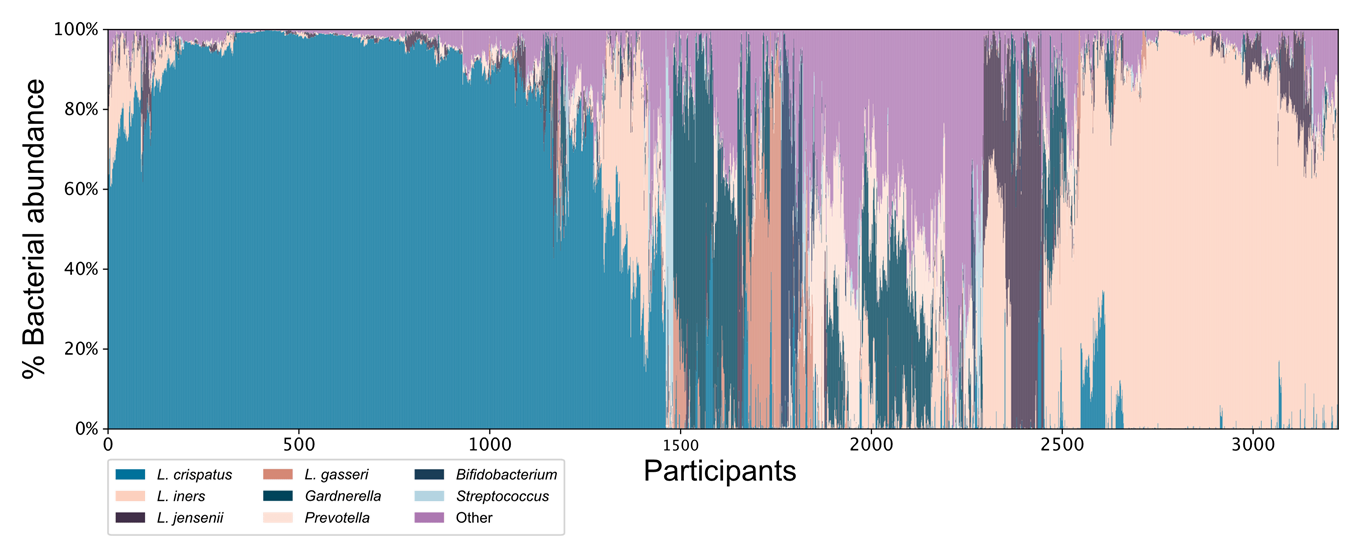

- Prof. Anukam describes his collaboration with Prof. Gregor Reid PhD early in his career, prompted by a paper claiming that African women did not have vaginal microbiomes dominated by lactobacilli. Subsequent work showed this was not the case – confounding factors contributed to the initial result.

- He cautions researchers against making conclusions about race or ethnicity when geographical variations or other factors could better account for the differences between groups. In studies it’s important to specify the geography as well as the other factors (dietary, cultural) that may impact the gut microbiome in these populations.

- There is a long history of fermented foods in Africa but not a lot of research has been done on them. In a 2009 paper with Prof. Reid, Prof. Anukam reported isolated lactic acid species from a fermented food called okpeye produced in Eastern Nigeria. The isolates showed potential for industrial applications.

- Most of his research studies are funded from outside Nigeria, with different sources of funding.

- ‘Parachute’ science is common in Africa, where researchers come into an African country, obtain samples and leave. He encourages researchers to involve local scientists to build capacity and allow them to do the analysis.

- Prof. Anukam describes a clinical trial he led on the skin microbiome and malodor in Nigerian youth. He found the skin microbiome in the armpit was altered if individuals used deodorants and antiperspirants; and these individuals kept having the same malodor issues. Individuals with less odor were found to have more lactobacilli on the skin, with differences in composition between men and women. They developed a topical cream to use as an intervention for 14 days, and found that lactobacilli on the skin increased and less odor was reported.

- The microbiome(s) of the male reproductive organs have not been studied very much. Semen has a microbiome, and this is shown by both culture and non-culture methods. It is dominated by lactobacilli, and this corresponds with semen quality. The evidence is mixed on the existence of testes and prostate microbiomes. A gut-testes connection may exist, however, as shown in mouse studies.

- Prof. Anukam says in a study of subjects seeking reproductive healthcare, different microbiomes were observed both in males and females having difficulty conceiving.

- The semen microbiome could play a significant role in reproduction – for example, it may produce metabolites that could affect the female reproductive tract and influence the environment for conception to take place. When doing in vitro fertilization, evidence has shown that if the samples are contaminated by pathogens, it can be difficult to achieve conception.

Episode links:

- Paper from 2009 on fermented foods: African traditional fermented foods and probiotics

- Paper from 2021 on skin malodor: Topical cream containing live lactobacilli decreases malodor-producing bacteria and downregulates genes encoding PLP-dependent enzymes on the axillary skin microbiome of healthy adult Nigerians

- Paper from 2021 on reproductive microbiomes: Microbiome Compositions From Infertile Couples Seeking In Vitro Fertilization, Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Methods: Any Correlation to Clinical Outcomes?

About Prof. Kingsley Anukam PhD:

Kingsley C Anukam is a research scientist in human microbiome and biotherapeutics with over 20 years experience. He shares his time between Canada and Nigeria as an adjunct professor at Nnamdi Azikiwe University where he assists in the training and supervision of post graduate students working in the area of probiotics, fermented foods, human microbiome, infectious diseases, laboratory diagnostics, human genomics and forensic DNA analysis. He had his graduate education in Nigeria and post doctorate training in Dr. Gregor Reid’s Lab at Lawson Health Research Institute and Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Western University, Canada. He is the first from Africa to show that vaginal microbiome of healthy Nigerian women is similar to women from other populations irrespective of geographical location. He has sequenced and annotated the full genome of over 10 Lactobacillus species of African origin mainly from the reproductive tract and African fermented foods in collaboration with Prof. Sarah Lebeer. He played a significant role in the formation of the DORA project, an ISALA-inspired citizen science for vaginal health in Nigeria. He has over 80 scientific research publications in peer-reviewed journals and listed among first 10 most cited researcher at Nnamdi Azikiwe University by Google Scholar. He is currently the Chief Editor, Journal of Medical Laboratory Science, and a peer-reviewer of several international journals.