Prebiotics do better than low FODMAPs diet

By Francisco Guarner MD PhD, Consultant of Gastroenterology, Digestive System Research Unit, University Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain

Bloating and visible abdominal distention after meals is a frequent complaint of people suffering from irritable bowel syndrome, but even generally healthy people sometimes have these complaints. These symptoms are thought to be due to fermentation of food that escapes our digestive processes. Some sugars and oligosaccharides end up at the far end of our small bowel and cecum, where they become food for our resident microbes.

To manage this problem, medical organizations recommend antibiotics to suppress the microbial growth in our small intestine (known as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or SIBO) or avoidance of foods that contain fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, called a low “FODMAP” diet. These approaches are generally successful in reducing symptoms, but do not provide permanent relief: symptoms typically return after the strategies are stopped.

Even worse, both approaches are known to disrupt the entire gut microbial ecosystem (not only at small bowel and cecum). Whereas a healthy microbial gut ecosystem has many different types of bacteria, antibiotics deplete them. The low FODMAP diet deprives beneficial bacteria (such as Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Lactobacillus and others) of the food they like to eat, and these species wane (see here).

Prof. Glenn Gibson, a founding father of prebiotic and synbiotic science, suggested that increasing ingestion of certain prebiotics could increase levels of bifidobacteria. These bifidobacteria in turn could prevent excessive gas production since they are not able to produce gas when fermenting sugars. (Instead, bifidobacteria product short chain fatty acids, mainly lactate, which are subsequently converted to butyrate by other healthy types of bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia.)

Prof. Gibson’s hypothesis was tested in pilot studies where volunteers ingested a prebiotic known as galacto-oligosaccharide (Brand name: Bimuno). Healthy subjects were given 2.8 g/day of Bimuno for 3 weeks. At first, they had more gas: significantly higher number of daily anal gas evacuations than they had before taking the prebiotic (see here). The volume of gas evacuated after a test meal was also higher. However, after 3 weeks of taking the prebiotic, daily evacuations and volume of gas evacuated after the test meal returned to baseline. The microbe populations also started to recover. The relative abundance of healthy butyrate producers in fecal samples increased and correlated inversely with the volume of gas evacuated. This suggested that the prebiotic induced an adaptation of microbial metabolism, resulting in less gas.

Then researchers launched a second study, also in healthy volunteers, to look at how the metabolic activity of the microbiota changed after taking this prebiotic. They showed that adaptation to this prebiotic involves a shift in microbiota metabolism toward low-gas producing pathways (see here).

A third controlled study (randomized, parallel, double-blind), this time in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders with flatulence, compared the effects of the prebiotic supplement (2.8 g/d Bimuno) plus a placebo diet (mediterranean-type diet) to a placebo supplement plus a diet low in FODMAPs. The study subjects were divided between these 2 diets, which they consumed for 4 weeks (see here). Both groups had statistically significant reductions in symptom scores during the 4-week intervention. Once subjects stopped taking the prebiotic, they still showed improved symptoms for 2 additional weeks (at this point, the study was completed). However, for subjects on the low-FODMAP diet, once the diet was stopped, symptoms reappeared. Very interestingly, these 2 diets had opposite effects on fecal microbiota composition. Bifidobacterium increased in the prebiotic group and decreased in the low-FODMAP group, whereas Bilophila wadsworthia (a sulfide producing species) decreased in the prebiotic group and increased in the low-FODMAP group.

The bottom line conclusion is that a diet including intermittent prebiotic administration might be an alternative to the low FODMAP diets that are currently recommended for people with functional gut symptoms, such as bloating and abdominal distention. Since low FOD MAP diets are low in fiber, the prebiotic option may provide a healthier dietary option.

- Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64(1):93–100.

- Mego M, Manichanh C, Accarino A, Campos D, Pozuelo M, Varela E, et al. Metabolic adaptation of colonic microbiota to galactooligosaccharides: a proof-of-concept-study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(5):670–80.

- Mego M, Accarino A, Tzortzis G, Vulevic J, Gibson G, Guarner F, et al. Colonic gas homeostasis: Mechanisms of adaptation following HOST-G904 galactooligosaccharide use in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(9):e13080.

- Huaman J-W, Mego M, Manichanh C, Cañellas N, Cañueto D, Segurola H, et al. Effects of Prebiotics vs a Diet Low in FODMAPs in Patients With Functional Gut Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1004-7.

Additional reading:

Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64(1):93–100.

Mego M, Manichanh C, Accarino A, Campos D, Pozuelo M, Varela E, et al. Metabolic adaptation of colonic microbiota to galactooligosaccharides: a proof-of-concept-study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(5):670–80.

Mego M, Accarino A, Tzortzis G, Vulevic J, Gibson G, Guarner F, et al. Colonic gas homeostasis: Mechanisms of adaptation following HOST-G904 galactooligosaccharide use in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(9):e13080.

Huaman J-W, Mego M, Manichanh C, Cañellas N, Cañueto D, Segurola H, et al. Effects of Prebiotics vs a Diet Low in FODMAPs in Patients With Functional Gut Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1004-7.

Halmos EP, Gibson PR. Controversies and reality of the FODMAP diet for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul;34(7):1134-1142. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14650. Epub 2019 Apr 4.

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was more somewhat daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), who liked to make stuff and sell it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the ‘staff’ of a new company.

Giving a lecture on beneficial microbes is hard enough to peers sitting in the back of the room, but to do so with young South Africans was more somewhat daunting. However, it proved to be a lot of fun especially when we had to identify kids who were good leaders (the boys all pointed to a girl), who liked to make stuff and sell it to others (two boys stood out). By the end, we had picked the ‘staff’ of a new company.

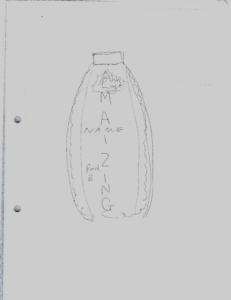

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob with the idea it would contain fermented maize. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

When we re-assembled to present the results, I was impressed with what could be created in such a short time. My favourite was the Amazing Maize, a bottle shaped like a corn cob with the idea it would contain fermented maize. It emphasized the importance of marketing and for products to taste and look good to be purchased.

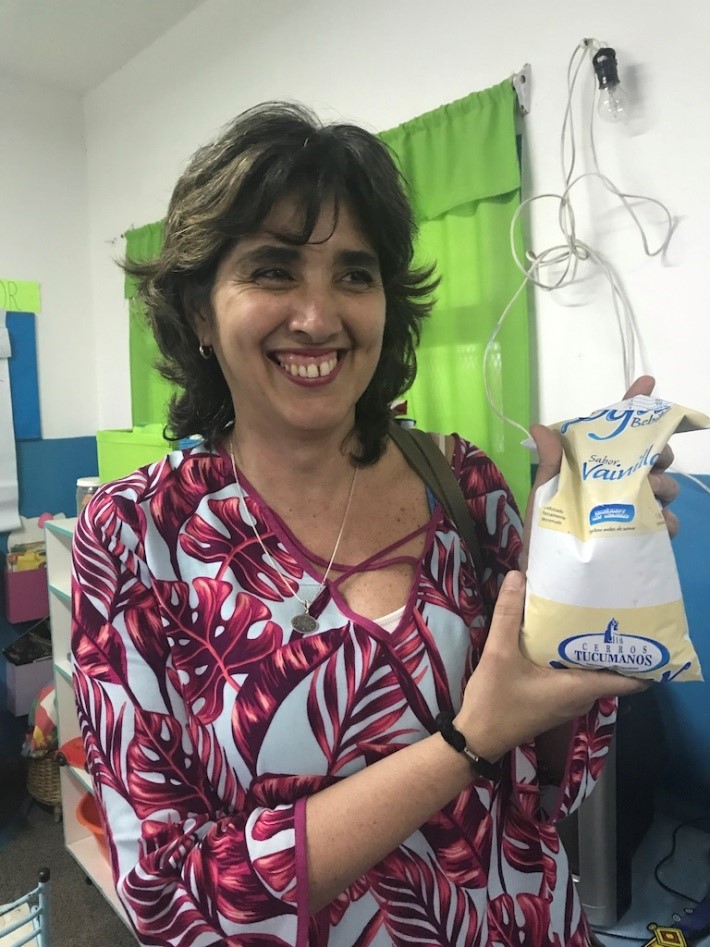

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product

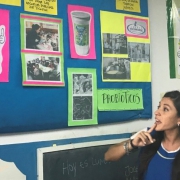

Senior Researcher Maria Pia Taranto and the Yogurito product Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina

Maria Luz Ovejero, a teacher at Primary School 252 Manuel Arroyo y Pinedo, explains probiotics to 4-6 year old children in Tucuman province in Argentina