Improving the quality of microbiome studies – STORMS

By Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD, ISAPP Executive Science Officer

In mid-March I attended the Gut Microbiota for Health annual meeting. I was fortunate to participate in a short workshop chaired by Dr. Geoff Preidis MD, PhD, a pediatric gastroenterologist from Baylor College of Medicine and Dr. Brendan Kelly MD, MSCE, an infectious disease physician and clinical epidemiologist from University of Pennsylvania. The topic of this workshop was “Designing microbiome trials – unique considerations.”

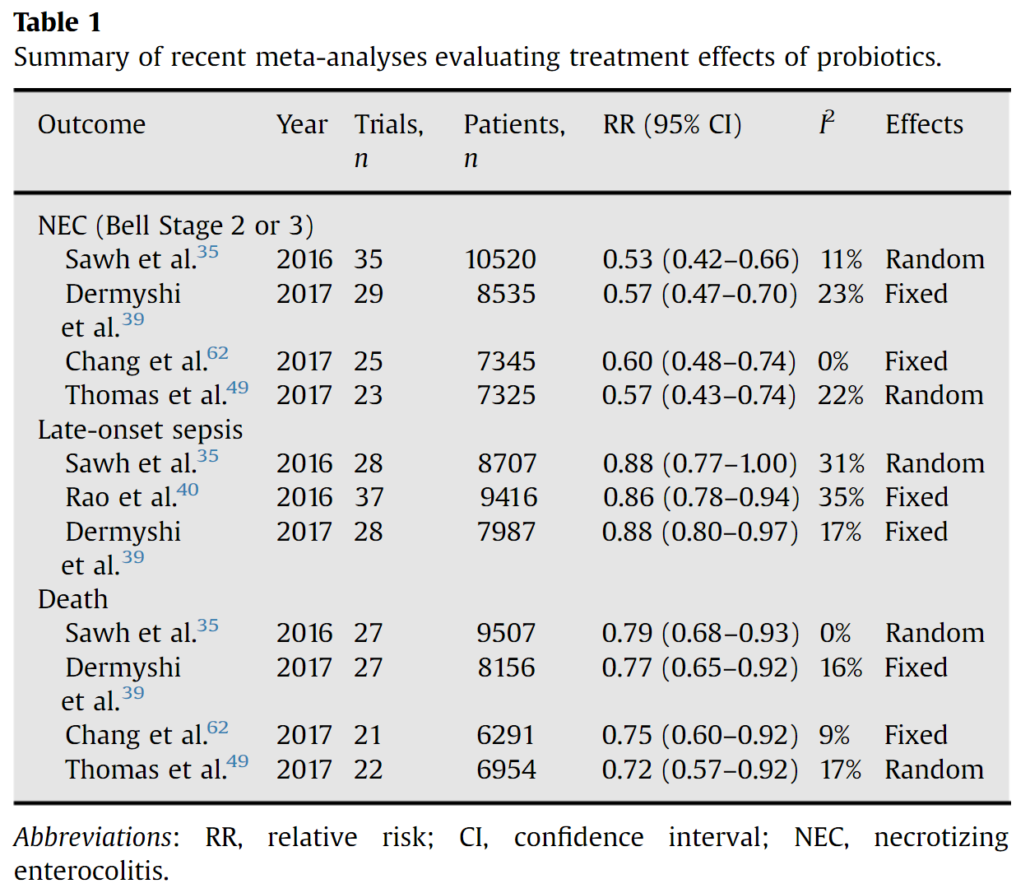

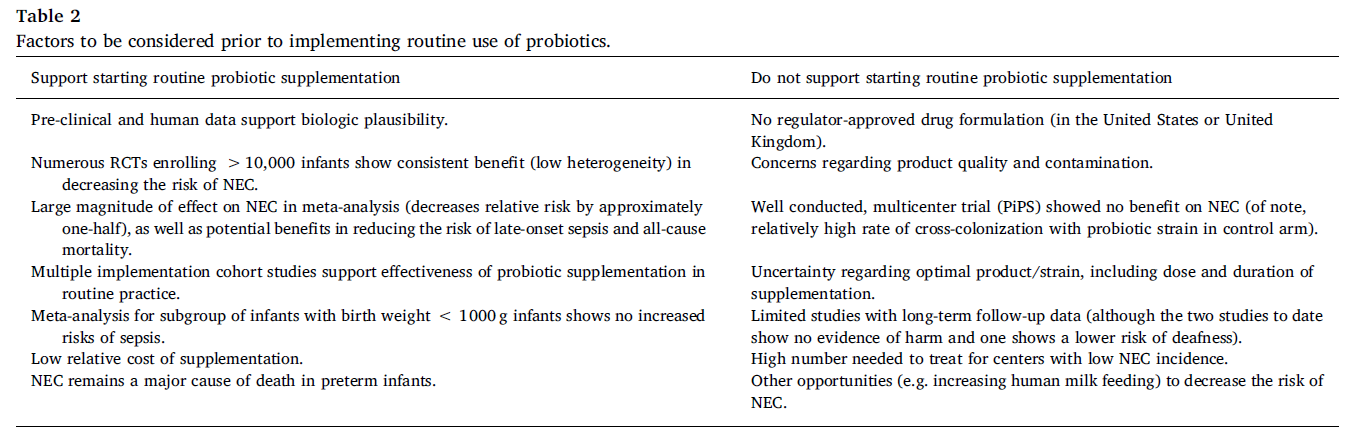

Dr. Preidis introduced the topic by recounting his effort (Preidis et al. 2020) to review evidence for probiotics for GI endpoints, including for his special interest, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). After a thorough review of available studies testing the ability of probiotics to prevent morbidity and mortality outcomes for premature neonates, he and the team found 63 randomized controlled trials that assessed close to 16,000 premature babies. Although the effect size for the different clinical endpoints was impressive and clinically meaningful, AGA was only able to give a conditional recommendation for probiotic use in this population.

Why? In part, because inadequate conduct or reporting of these studies led to reduced confidence in their conclusions. For example, proper approaches to mitigate selection bias must be reported. Some examples of selection bias include survival bias (where part of the target study population is more likely to die before they can be studied), convenience sampling (where members of the target study population are not selected at random), and loss to follow-up (when probability of dropping out is related to one of the factors being studied). These are important considerations that might influence microbiome results. If the publication on the trial does not clearly indicate how these potential biases were addressed, then the study cannot be judged as low risk of bias. It’s possible in such a study that bias is addressed correctly but reported incompletely. But the reader cannot ascertain this.

With an eye toward improving the quality and transparency of future studies that include microbiome endpoints, Dr. Preidis shared a paper by a multidisciplinary team of bioinformaticians, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and microbiologists titled Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies (STORMS): A Reporting Checklist for Human Microbiome Research.

Dr. Preidis kindly agree to help the ISAPP community by answering a few questions about STORMS:

Dr. Preidis, why is the STORMS approach so important?

Before STORMS, we lacked consistent recommendations for how methods and results of human microbiome research should be reported. Part of the problem was the complex, multi-disciplinary nature of these studies (e.g., epidemiology, microbiology, genomics, bioinformatics). Inconsistent reporting negatively impacts the field because it renders studies difficult to replicate or compare to similar studies. STORMS is an important step toward gaining more useful information from human microbiome research.

One very practical outcome of this paper is a STORMS checklist, which is intended to help authors provide a complete and concise description of their study. How can we get journal editors and reviewers to request this checklist be submitted along with manuscripts for publication?

We can reach out to colleagues who serve on editorial boards to initiate discussions among the editors regarding how the STORMS checklist might benefit reviewers and readers of a specific journal.

How does this checklist differ from or augment the well-known CONSORT checklist?

Whereas the CONSORT checklist presents an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials, the STORMS checklist facilitates the reporting of a comprehensive array of observational and experimental study designs including cross-sectional, case-control, cohort studies, and randomized controlled trials. In addition to standard elements of study design, the STORMS checklist also addresses critical components that are unique to microbiome studies. These include details on the collection, handling, and preservation of specimens; laboratory efforts to mitigate batch effects; bioinformatics processing; handling of sparse, unusually distributed multi-dimensional data; and reporting of results containing very large numbers of microbial features.

How will papers reported using STORMS facilitate subsequent meta-analyses?

When included as a supplemental table to a manuscript, the STORMS checklist will facilitate comparative analysis of published results by ensuring that all key elements are reported completely and organized in a way that makes the work of systematic reviewers more efficient and more accurate.

I have been struck through the years of reading microbiome research that primary and secondary outcomes seem to be rarely stated up front. Or if such trials are registered, for example on clinicaltrials.gov, the paper does not necessarily focus on the pre-stated primary objectives. This approach runs the risk of researchers finding the one positive story to tell out of the plethora of data generated in microbiome studies. Will STORMS help researchers design more hypothesis driven studies?

Not necessarily. The STORMS checklist was not created to assess study or methodological rigor; rather, it aims to aid authors’ organization and ease the process of reviewer and reader assessment of how studies are conducted and analyzed. However, if investigators use this checklist in the planning phases of a study in conjunction with sound principles of study design, I believe it can help improve the quality of human microbiome studies – not just the writing and reporting of results.

Do you have any additional comments?

One of the strengths of the STORMS checklist is that it was developed by a multi-disciplinary team representing a consensus across a broad cross-section of the microbiome research community. Importantly, it remains a work in progress, with planned updates that will address evolving standards and technological processes. Anyone interested in joining the STORMS Consortium should visit the consortium website (www.stormsmicrobiome.org).

See related blog: ISAPP take-home points from American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on probiotic use for gastrointestinal disorders