Episode 37: Targeting the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease, with Prof. Harry Sokol MD PhD

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS

The ISAPP hosts discuss the microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with leading expert Prof. Harry Sokol MD PhD, who is Professor of Gastroenterology at Saint Antoine Hospital and has positions with Sorbonne University and the Micalis Institute, INRAE in Paris, France. Sokol talks about the specific gut bacteria that seem to be important in IBD, as well as the challenge of targeting the gut microbiome for therapeutic effects.

Key topics from this episode:

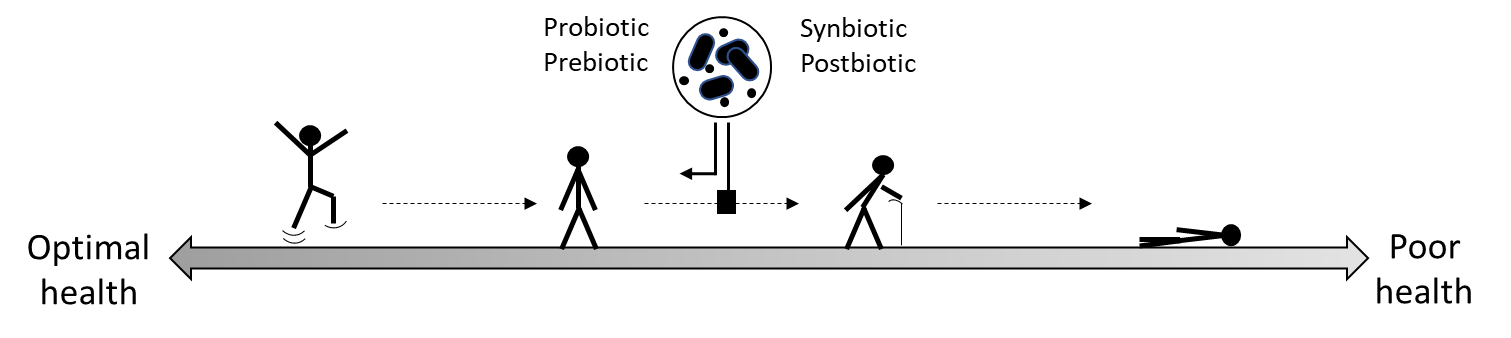

- Dr. Sokol says that while more and more gastroenterologists see the gut microbiome as relevant to disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, the microbiome is not yet an important part of clinical practice. Fecal microbiota transplantation is widely used for recurrent C. difficile infection, but its utility in chronic disease is not established.

- Earlier in his research career, he started with the ‘global description’ strategy of surveying the gut microbiome of patients with IBD using the available scientific tools. More recently, Dr. Sokol has focused on ‘candidate microorganisms’ to target such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, or F. prau.

- How do scientists know F. prau is important for IBD? First, those with IBD have less of these bacteria. And patients with Crohn’s disease who have the lowest amounts in their gut microbiomes have the highest chance of disease relapse. Furthermore, these bacteria are human-specific and are found at a very high prevalence in healthy individuals – it makes up between 5 and 10% of the average person’s gut microbiome. A recent prospective study (GEM) also found that F. prau was one of the bacterial species that decreased even before the onset of inflammation and disease. Now Dr. Sokol and others are exploring the therapeutic uses of these bacteria.

- The ultimate goal with IBD is to use treatments that target the microbiome alongside treatments that target the host.

- A decrease in F. prau within the gut microbiome is not specific to IBD; it’s also seen in people with IBS and diarrhea. These bacteria may have multiple effects in the body.

- Dr. Sokol’s group worked on CARD9, an IBD susceptibility gene. The gene’s effect on phenotype occurs through the microbiome, because in mice, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was enough to transfer the susceptibility to colitis. The microbiota also transferred an immune defect in IL-22 production, related to an alteration in tryptophan metabolism in the microbiome. Normally some bacteria in the microbiota use tryptophan to produce indoles, which lead to the production of IL-22, but this process was altered in the mice that received the FMT.

- This tryptophan metabolism in the microbiome is altered in IBD as well as other diseases. It’s one of the major functions of the gut microbiome, similar to short-chain fatty acid production and bile acid metabolism.

- As for F. prau, challenges remain with growing and scaling up production for industrial use, but currently Dr. Sokol and collaborators have a method that works. Perhaps eventually they will zone in on the molecules produced by the bacteria, but then again the bacteria may be more effective because it may address different mechanisms of action and different targets simultaneously.

Episode abbreviations and links:

- Dr. Sokol mentions two scientists who initially got him interested in the gut microbiome: Prof. Philippe Marteau MD PhD and Prof. Joël Doré PhD

- Recent work on CARD9 & the gut microbiota in colitis: Dissecting the respective roles of microbiota and host genetics in the susceptibility of Card9-/- mice to colitis

- Review on the potential therapeutic applications of F. prau: Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications

Additional resources:

- New global guidelines for probiotics and prebiotics for gut health and disease. ISAPP blog on current evidence for probiotic use in gastrointestinal diseases, including IBD.

About Prof. Harry Sokol MD PhD:

Harry Sokol is Professor in the Gastroenterology department of Saint-Antoine Hospital (APHP, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France). the co-director of the Microbiota, Gut & Inflammation team (INSERM CRSA UMRS 938, Sorbonne Université, Paris), group leader in Micalis institute (INRAE) and coordinator of the “Paris Center for Microbiome Medicine” (www.fhu-pacemm.fr/). He is an internationally recognized expert in the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and gut microbiota fields, in which he has published more than 330 papers in major journals. He is the current president of the French group of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation, and the head of the APHP Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Center. His work on the role of gut microbiota in IBD pathogenesis led to landmark papers, including the identification of the pivotal role of the commensal bacteria Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in gut homeostasis and IBD. Currently, his work focuses on deciphering gut microbiota–host interactions in health and disease to better understand their role in pathogenesis and develop innovative treatments. Harry received two grants from the European Research Council (ERC) in 2016 and 2022, and he is a member of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD). Since 2020, he is recognized as a Highly Cited Researcher (Clarivate, Web of Science). Harry Sokol is currently Associate Editor for Gastroenterology. Harry Sokol co-founded Exeliom biosciences (https://www.exeliombio.com/).

Find Harry on X/Twitter: @h_sokol