1-9 of 9 results

-

A guide to the new FDA Qualified Health Claim for yogurt

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kimchi, and fermented pickles have traditionally been associated with health benefits in countries around the… -

Are the microbes in fermented foods safe? A microbiologist helps demystify live microbes in foods for consumers

Since very early in my career I was drawn to science communication. I feel that rather than just producing my… -

Designing Probiotic Clinical Trials: What Placebo Should I Use?

By Daniel J. Merenstein, MD, Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Director of Research Programs, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington… -

Can fermented or probiotic foods with added sugars be part of a healthy diet?

By Dr. Chris Cifelli, Vice President of Nutrition Research, National Dairy Council, Rosemont IL, USA What about added sugar in… -

Ambient yogurts make a global impact

By Prof. Bob Hutkins, PhD, University of Nebraska Lincoln, USA Quick, which country consumes the most yogurt? Must be France?… -

Locally produced probiotic yogurt for better nutrition and health in Uganda

By Prof. Seppo Salminen, Director of Functional Foods Forum, University of Turku, Turku, Finland Can locally produced probiotic yogurt be… -

Bulgarian yogurt: An old tradition, alive and well

By Mariya Petrova, PhD, Microbiome insights and Probiotics Consultancy, Karlovo, Bulgaria Family and family traditions are very important to me. Some… -

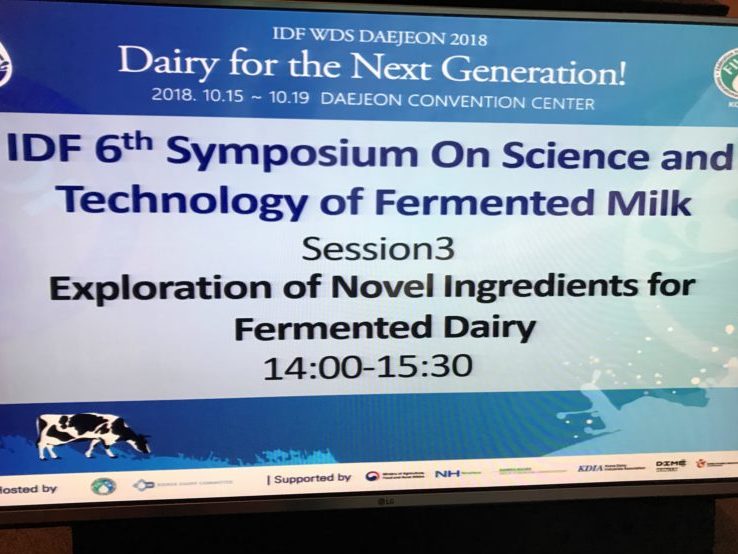

International Dairy Summit 2018 in Daejeon in South Korea

By Prof. Seppo Salminen PhD, University of Turku, Finland The International Dairy Federation (IDF) convenes annual meetings that bring together… -

Fermented Foods in Nutrition & Health

November 2017. Discussed at International Union of Nutritional Sciences (IUNS) Congress session. By Prof. Seppo Salminen, Director of the Functional Foods…