The gut mycobiome and misinformation about Candida

By Prof. Eamonn Quigley, MD, The Methodist Hospital and Weill Cornell School of Medicine, Houston

As a gastroenterologist, I frequently meet with patients who are adamant that a Candida infection is the cause of their ailments. Patients experiencing a range of symptoms, including digestive problems, sometimes believe they have an overgrowth of Candida in their gastrointestinal (GI) tract and want to know what to do about it. Their insistence is perhaps not surprising, given how many many websites and social media ‘gurus’ share lists of symptoms supposedly tied to Candida infections. Even cookbooks exist with recipes specifically tailored to “cure” someone of Candida infection through dietary changes. Some articles aim to counter the hype – for example, an article titled “Is gut Candida overgrowth actually real, and do Candida diets work?” Yet patients are too often confused about the evidence on Candida and other fungi in the GI tract. In a 2021 ISAPP presentation on the gut mycobiome, I provided a clinical perspective on fungal infections and the related evidence base.

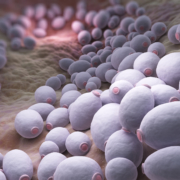

Fungal infections do occur

Much of the misinformation I encounter on Candida infections focuses on selling a story that encourages people to blame Candida overgrowth as the cause of their symptoms and undertake expensive or complicated dietary and supplement regimens to “cure” the infection. This is not to say that fungal infections do not take place in the body. Fungal infections, from Candida or other fungi, frequently occur on the nails or skin. Patients taking oral or inhaled steroids may develop Candida infections in the oropharynx and esophagus. Immunocompromised patients also face a greater risk of Candidiasis and Candidemia—these include HIV patients; patients undergoing chemotherapy; transplant patients; and patients suffering from malnutrition.

Fungal infections are rare in the GI tract

Regardless, instances of documented Candida infection in the GI tract remain few in number. One study published in the 90s reported 10 patients hospitalized with severe diarrhea1. These patients suffered from chronic illness, underwent intense antimicrobial treatment or chemotherapy, and faced severe outcomes such as dehydration—and clinicians consistently identified the growth of Candida albicans in the patient fecal samples. Other studies on the matter lack the clinical evidence to conclude that fungal infections drive GI disease. A study examining small intestinal fungal overgrowth identified instances of fungal overgrowth among 150 patients with unexplained symptoms2. However, the lack of documentation of response to an antifungal treatment protocol makes it difficult to attribute the observed symptoms to the presence of fungal organisms.

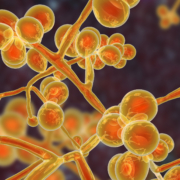

The gut mycobiome in IBS

The gut microbiome has taken centre stage in common discourse about gut health. In line with this movement, my colleagues at Cork investigated the fungal members of the gut microbiome – that is, the gut mycobiome – in the guts of patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)3 to ascertain whether there was any correlation with symptoms. This effort revealed DNA sequences belonging to many fungal species. However, no significant differences in the number of fungal species were observed between IBS patients and volunteers. A smaller study done on a Dutch cohort, on the other hand, detected significantly reduced total fungal diversity among IBS patients4. So, it’s not yet clear whether mycobiome differences exist across populations with IBS.

Studying the gut mycobiome for further insights

The few studies that have examined the human gut mycobiome expose the need to answer basic questions about the fungal components of the gut microbiome. For instance, what is the gut mycobiome composition among people not suffering from GI-related symptoms? Efforts to answer these questions would require longitudinal sample collection to account for the high turnover of microbes in the GI tract. We would also need to perform stool measures not typically performed in the clinic to better correlate fungal overgrowth with GI-related symptoms. Overall, any gut mycobiome study requires careful and detailed experimental design.

We also have to consider where the gut mycobiome originates. A recent study in mSphere showed that the increased amount of DNA belonging to S. cerevisiae in stool samples coincided with the number of times subjects consumed bread and other fungi-rich foods5. S. cerevisiae also failed to grow in lab conditions mimicking the gut environment after 7 days of incubation. These findings suggest that the fungi identified in gut mycobiome profiles are not persistent gut colonizers, but transient members of the gut microbiome that come from the food we digest or our saliva.

A survey of the literature on the gut mycobiome and fungal infections in the GI tract highlights the need to conduct more studies on the role fungi play in gut and overall health. My clinical approach when I encounter someone claiming to have GI symptoms caused by Candida infection is a skeptical, yet empathetic response. Through proper communication of the evidence, we can investigate the origin of symptoms together and identify the best treatment methods for any GI-related disease, whether caused by fungal infections or not.

ISAPP held a mini-symposium featuring six short lectures that explore different aspects of the human mycobiome, including research, clinical and industry perspectives. See here for the replay, with Dr. Quigley’s talk at 1:12:30.

References

(1) Gupta, T. P.; Ehrinpreis, M. N. Candida-Associated Diarrhea in Hospitalized Patients. Gastroenterology 1990, 98 (3), 780–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(90)90303-i.

(2) Jacobs, C.; Coss Adame, E.; Attaluri, A.; Valestin, J.; Rao, S. S. C. Dysmotility and Proton Pump Inhibitor Use Are Independent Risk Factors for Small Intestinal Bacterial and/or Fungal Overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013, 37 (11), 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12304.

(3) Das, A.; O’Herlihy, E.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P. W.; Jeffery, I. B. The Fecal Mycobiome in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Sci Rep 2021, 11 (1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79478-6.

(4) Botschuijver, S.; Roeselers, G.; Levin, E.; Jonkers, D. M.; Welting, O.; Heinsbroek, S. E. M.; de Weerd, H. H.; Boekhout, T.; Fornai, M.; Masclee, A. A.; Schuren, F. H. J.; de Jonge, W. J.; Seppen, J.; van den Wijngaard, R. M. Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis Is Associated With Visceral Hypersensitivity in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Rats. Gastroenterology 2017, 153 (4), 1026–1039. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.004.

(5) Auchtung, T. A.; Fofanova, T. Y.; Stewart, C. J.; Nash, A. K.; Wong, M. C.; Gesell, J. R.; Auchtung, J. M.; Ajami, N. J.; Petrosino, J. F. Investigating Colonization of the Healthy Adult Gastrointestinal Tract by Fungi. mSphere 2018, 3 (2), e00092-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00092-18.