Photo by http://benvandenbroecke.be/ Copyright, ISAPP 2019.

Microbiomes

High-throughput DNA sequencing technologies and advanced computational techniques of the past few decades have allowed significant advancements in knowledge about human-associated microorganisms. Different areas of the human body—digestive tract (‘gut’), skin, vaginal tract, oral cavity, and others—are home to different communities of microorganisms, called microbiotas. The word microbiome generally refers to the microorganisms in a defined environment (e.g. the human colon) along with the environment itself. While microbiome and microbiota are sometimes used interchangeably, microbiota properly refers to the microorganisms themselves: bacteria, archaea, lower and higher eukaryotes, and viruses in a defined environment. All of these microorganisms comprise the microbiota, even though many “microbiome” studies only focus on the bacterial components.

It is now clear that the human microbiota plays important roles in health and disease.

The gut microbiota

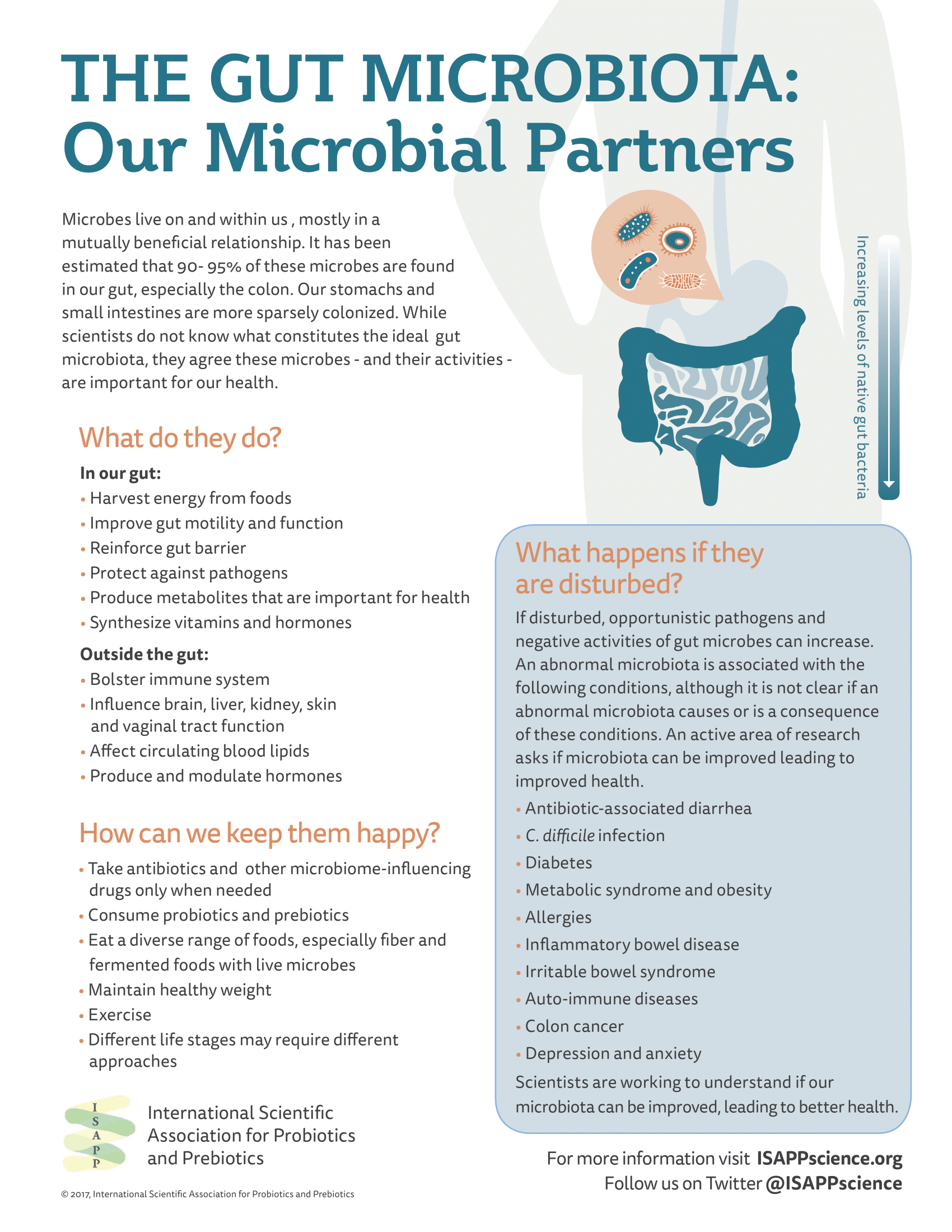

The gut microbiota is the most studied microbiota associated with the human body, with the digestive tract containing the highest density of human-associated microorganisms. Bacteria in the gut harvest energy from food, produce bioactive substances such as neurotransmitters, enzymes, short chain fatty acids, and vitamins, play an important role in programming the immune system, and may participate in metabolic functions.

To date, researchers have been unable to define a ‘healthy gut microbiota’ because the community of gut microbes varies greatly among healthy people. Differences in gut microbiota composition compared to health controls have been demonstrated in people with various diseases or conditions, but in most cases, microbiota differences have not been shown to cause any disease.

Diet and medications are important factors that account for gut microbiota variability in large cohort studies. Antibiotics are a particularly powerful way to alter the gut microbiota: when someone is on antibiotics, the microbial community is altered drastically throughout the course of the medication but microbes typically return to their baseline levels (or close to baseline levels) after the treatment ends.

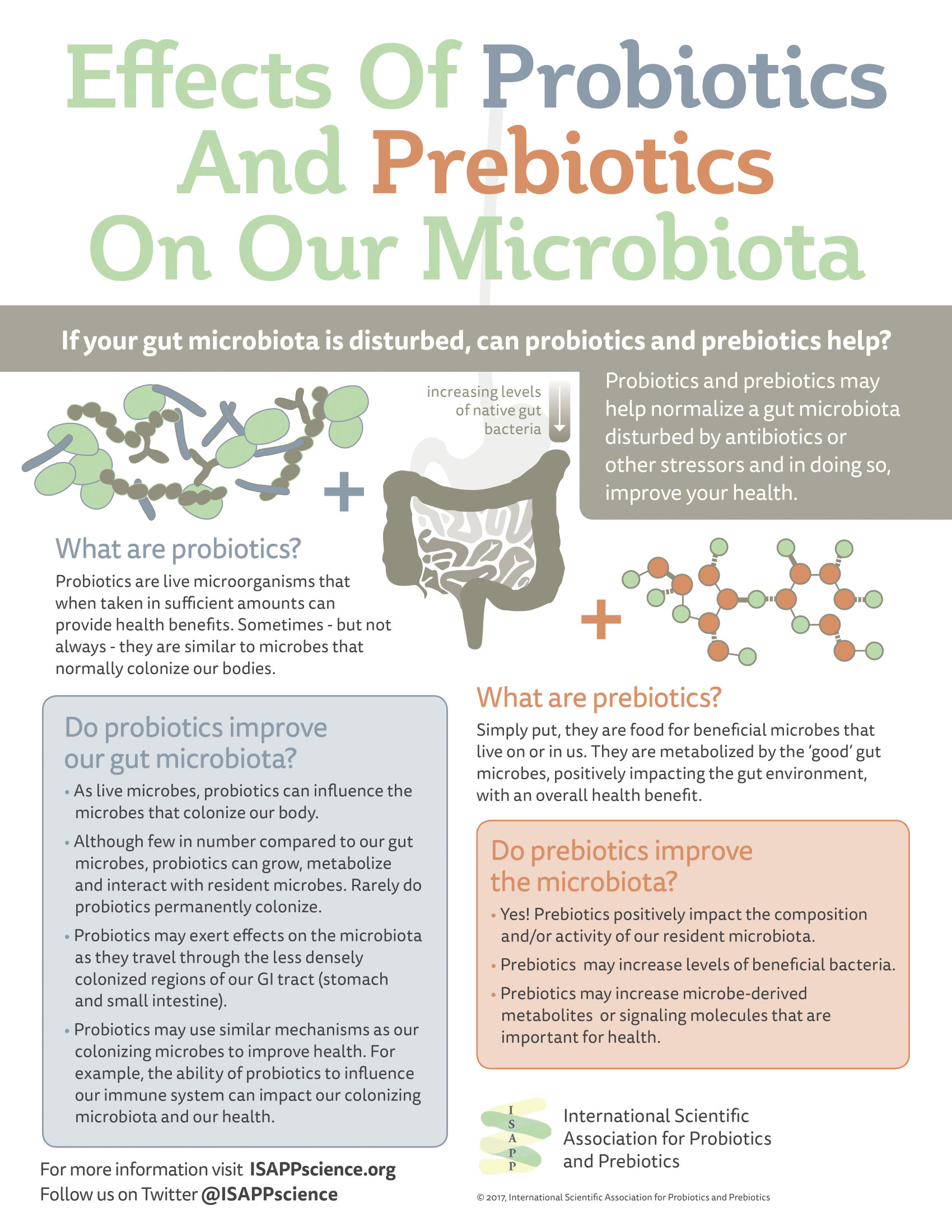

Dietary changes may also modulate the gut microbiota. Probiotics, prebiotics, fermented foods, and fiber are dietary means of influencing the gut microbiota composition or metabolic activities. Indeed, prebiotics in particular must by definition have a mechanism of action that involves their selective utilization by gut microorganisms.

See here for a blog post describing the limitations of microbiome measurement and how to interpret microbiome experiments.