Photo by http://benvandenbroecke.be/ Copyright, ISAPP 2019.

The term ‘probiotic’ was defined in 2001 by an Expert Consultation of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization (FAO/WHO). The following year, FAO/WHO published Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Foods, written, by an Expert Working Group that met prior to ISAPP’s inaugural meeting. In 2013, ISAPP convened an Expert Panel to review the term probiotic and literature surrounding it. The net result was a publication reiterating the definition with minor grammatical changes: “Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” This is the widely accepted scientific definition of probiotics around the world.

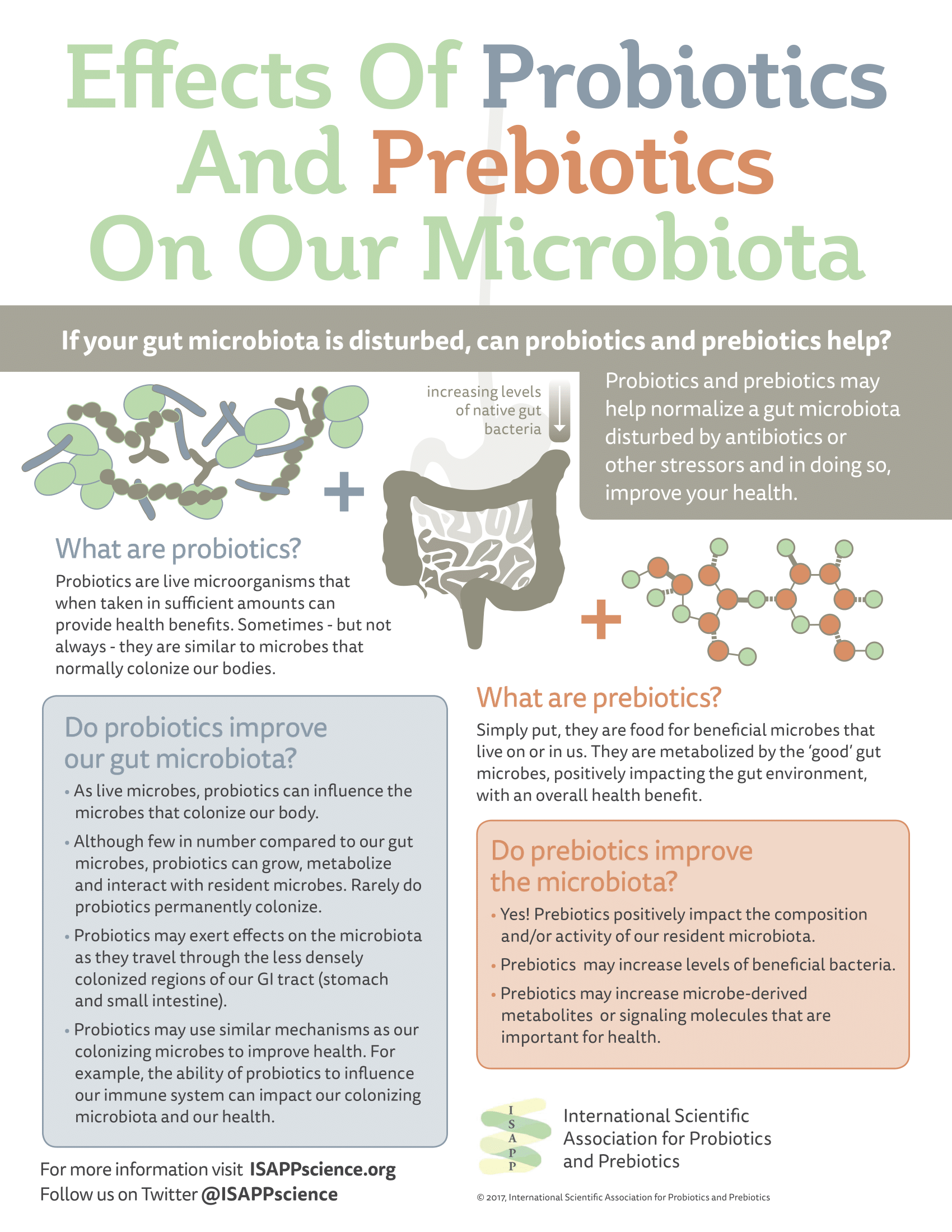

Live microorganisms may be present in many foods and supplements, but only characterized strains with a scientifically demonstrated effect on health should be called probiotics. Live microbes present in traditional fermented foods and beverages such as kombucha, sauerkraut, and kimchi typically do not meet the required evidence level for probiotics, since their health effects have not been confirmed and the mixtures of microbes are largely uncharacterized (see ISAPP infographic).

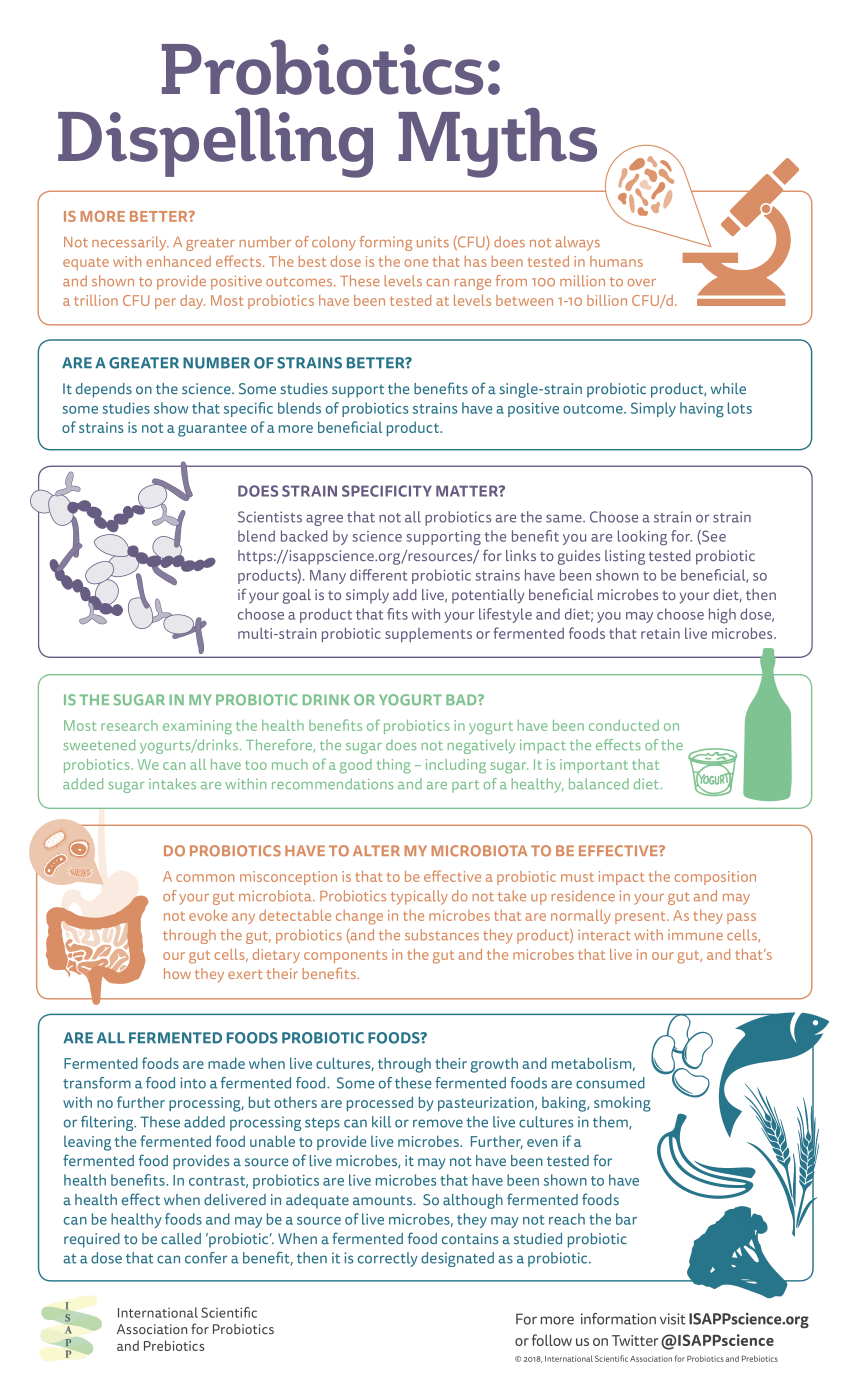

Probiotics are known by genus, species, and strain: for example, Lactobacillus acidophilus ABC. The strain designation is important, as different strains of the same species may have different health effects. Dose is also a consideration, and a probiotic consumed at a higher dose may not necessarily have a greater health benefit than one consumed at a lower dose. The dose should match the level shown in an efficacy study to confer a benefit.

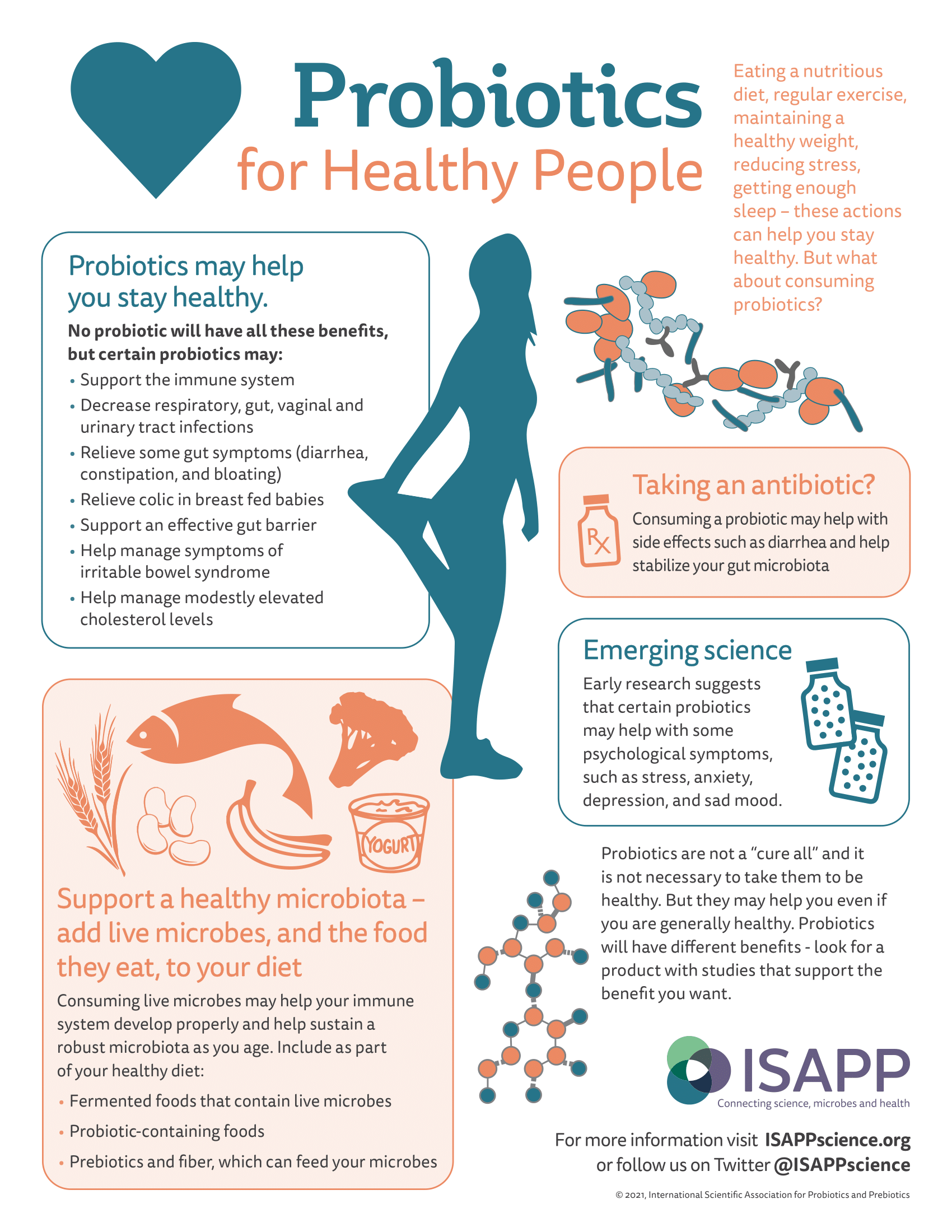

Probiotic products (usually dietary supplements or foods) may be recommended for different conditions or symptoms an individual is experiencing. Decades of study on specific probiotic strains have revealed particular health benefits:

- Helping reduce the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- Helping manage digestive discomfort (including in irritable bowel syndrome)

- Helping reduce colic symptoms in breastfed babies and occurrence of atopic issues such as eczema in infants

- Helping reduce necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants

- Helping reduce symptoms of lactose maldigestion

- Treating acute pediatric infectious diarrhea

- Decreasing the risk or duration of upper respiratory tract infections (such as the common cold) or gut infections

However, remember that not all these benefits will be delivered by any one product.

An increasing number of studies also support probiotic health benefits beyond the digestive tract, including oral, liver, skin, vaginal and urinary tract health.

A robust safety profile has been documented in clinical trials for many probiotic strains. However, for certain at-risk populations, such as premature infants, immunocompromised individuals, those with a serious illness, and those with ‘short gut’, certain concerns arise. A manuscript describing precautions has been published.

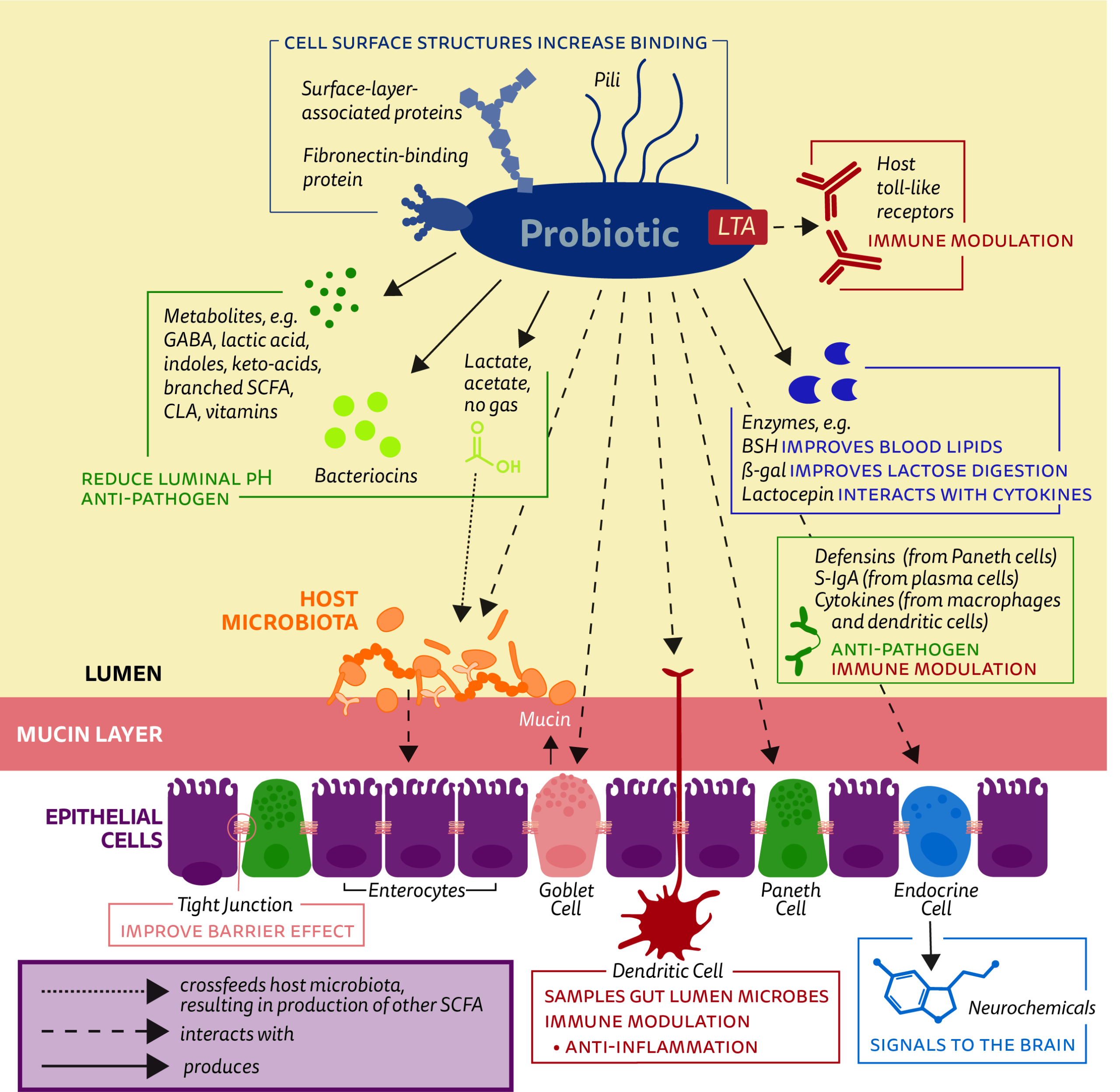

Figure showing some key mechanisms investigated as mediators of beneficial effects of ‘traditional’ probiotics.

Mechanisms that drive probiotic benefits are an active area of research and in some cases may be known. However, confirming mechanisms is challenging and often they remain unconfirmed in humans even though a health benefit has been demonstrated. Further, experts suspect that multiple mechanisms may act in concert to elicit a health benefit. A common misconception is that probiotics need to alter the gut microbiota in order to be effective. In fact, in general probiotics have not been shown to take up permanent residence in the gut despite documented health benefits.

See here for resources on probiotics and evidence on their efficacy for various conditions.

Dietary / nutritional use of probiotics is covered in ISAPP’s continuing education course for dietitians, available through Today’s Dietitian.